Click the highlighted text for more information about me or my consulting services at The Future of Publishing.

September 5, 2025 (correcting errors; updating some sources)

Here are the top data sources for the newspaper industry, primarily in the United States, and with links to data in the UK and Canada:

- An unbiased and authoritative source of information about what’s happening in the newspaper industry is provided by the Pew Research Center, under News Habits & Media. Its annual State of the News Media report is essential reading. 6 Key Takeaways About the State of the News Media in 2020 includes the insight that in 2020 “for the first time, newspapers made more money from circulation than from advertising.”

- Newspaper associations include WAN-IFRA — World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers, the U.S. News Media Alliance, NMA (formerly known as the Newspaper Association of America), the News Media Association in the U.K., and News Media Canada. As is the case in other industries, these associations guard most of their data for members only.

- Latest U.S. weekly circulation and ad revenue data as calculated by Pew: The peak year was 1984 (perhaps appropriately). The 2020 (estimated) number is some 38% of that. The same link also provides insight into digital circulation data as well as advertising and circulation revenue (39% comes from digital as of 2020, up from 17% in 2011).

- A range of U.K. newspaper industry data here and here.

- The latest Canadian daily newspaper circulation numbers are here.

- The in-depth 171-page 2025 Reuters Institute Digital News Report finds, unsurprisingly, that “engagement with traditional media sources such as TV, print, and news websites continues to fall, while dependence on social media, video platforms, and online aggregators grows.”

- The American Press Institute offers a range of research as does Northwestern University’s The State of Local News 2024.

- The Poynter Institute, in always an excellent resource, “a nonprofit media institute and newsroom that provides fact-checking, media literacy and journalism ethics training to citizens and journalists.”

- Editor & Publisher magazine is “The Authoritative Voice of NewsMedia Since 1884.”

Last full update: July 1, 2013. Corrections and updated links, September 9, 2021. This piece is, in part, dated, but as I review it in 2021, I see that the story remains largely unchanged — the data is just more troubling than it was 8 years ago.

Introduction to the Future of Newspapers

“Newspapers in this country are not dying, they are committing suicide.”

‒ Samir “Mr. Magazine” Husni

“It’s nice to see that the printed word is still, at least for now, the most powerful medium for reporting on the death of the printed word.”

‒ From The Onion, May 2008

The newspaper industry leads the charge to provide compelling proof that the Internet really is destroying traditional ink-on-paper publishing. The data has been troubling for a long time, and gets more convincing each day. A lot of analyses gloss over the data which demonstrates that the decline in newspaper readership and circulation easily predates the Internet. The story of the decline of the daily newspaper goes beyond the web. Furthermore the U.S. trends are not fully mirrored worldwide — is that because of lagging indicators or fundamentally different forces at work?

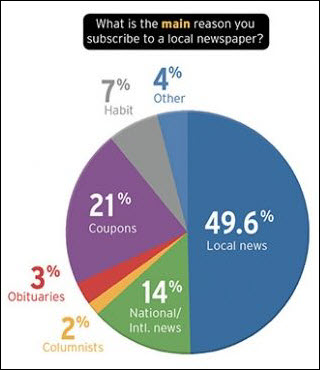

The enduring strength of newspapers is their local coverage, from community news to financial to entertainment. The reality is that city newspapers have more “feet on the ground” than any of the competing city web sites. The smartest newspaper managers are translating their community strength onto the web. Community newspapers and other weekly newspapers seem to be largely avoiding the fate of their daily brethren.

Source: Ad Age/Ipsos Observer American Consumer Survey

My overall rating for the future of the traditional newspaper industry, first in North America, and spreading rapidly to all developed countries, is very negative. My hopes for a renaissance for the industry, strong.

Newspaper Industry Overview

The illustration above appeared on the cover of the August 24, 2006 edition of The Economist. The subhead was “The most useful bit of the media is disappearing. A cause for concern, but not for panic.” The article is essentially optimistic. A key paragraph states: “The usefulness of the press goes much wider than investigating abuses or even spreading general news; it lies in holding governments to account-trying them in the court of public opinion. The Internet has expanded this court. Anyone looking for information has never been better equipped. People no longer have to trust a handful of national papers or, worse, their local city paper. News-aggregation sites such as Google News draw together sources from around the world. The website of Britain’s Guardian now has nearly half as many readers in America as it does at home.”

Is the picture so rosy?

On the surface, newspaper publishing in North America appears to be in big trouble; but then, the newspaper industry been in ever-increasing trouble for a long time.

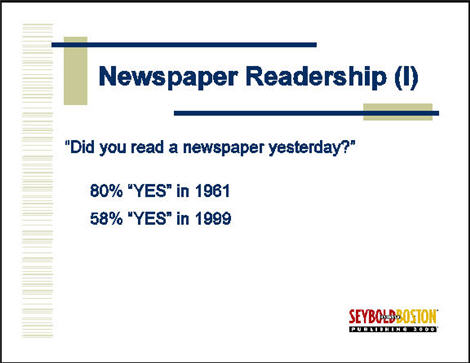

When I first began studying the future of publishing, around 2000, I offered this slide (based on a data source I can no longer locate ‒ sorry). (There is some interesting multi-year Gallup reporting here.)

Beyond that figure is one reported in The New York Times on March 26, 2007: “Newspaper circulation nationally reached its peak in 1984, when there were 1,600 morning and afternoon paid dailies with a circulation of 63 million….Today there are 1,450 paid dailies with a circulation of 53 million.” (2018: 1,279 daily newspapers. Circulation: 28.6 million for weekday and 30.8 million for Sunday.)

An article from late 2006 in the American Journalism Review takes the newspaper circulation data a step further in pointing out that “in 1950 there were 1,772 dailies with a total circulation of 53.8 million and 549 Sunday papers with 46.6 million. But since 1980, the number and circulation of dailies has declined fairly steadily, slipping to 1,452 last year, with circulation down to 53.3 million — below where it was 55 years ago, despite nearly a doubling in the size of the national population.” (Italics mine.)

Clearly this is a troubled medium. Equally clear is that the problem in newspaper circulation pre-dates the Internet by some years. Theories abound. Radio and television surely shoulder some of the blame; just as likely is that changing lifestyles impacted newspaper readership regardless of competing media.

The Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) self-refers as the “Gold Standard in Media Audits” and is the place to go if you want to find out current U.S. newspaper or magazine circulation figures. (In it has since changed its name to the Alliance for Audited Media, “to more accurately portray its evolving leadership in media verification.”)

Although a non-profit organization, it was formed by the interested parties: advertisers, ad agencies and publishers. Unfortunately you must be a member — they’re not giving this “sensitive” information away — and so it’s impossible for the public to get up-to-the-minute newspaper circulation data (one needs to pony up somewhere between $100 and $2500 for an associate membership). You can find some generic data here but not specifics.

But the ongoing decline in newspaper circulation in North America is not a well-kept secret, and if the ABC won’t spill the beans, others will.

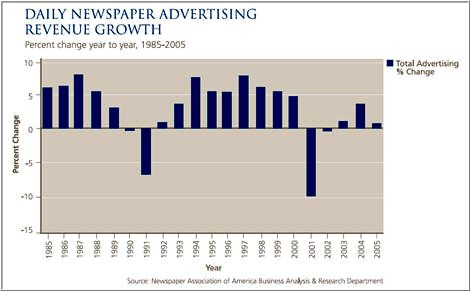

“Nielsen has local newspapers down 7.3 percent from the first half of 2007 and national newspapers down 8.1 percent. (Robert) Coen is forecasting declines of 8 percent and 7 percent for the full year, respectively, while TNS is projecting a decline of just under 1 percent for all newspapers.”

A May 2005 article in The Washington Post reported that “circulation at 814 of the nation’s largest daily newspapers declined 1.9 percent over the six months ended March 31 compared with the same period last year…The decline continued a 20-year trend in the newspaper industry as people increasingly turn to other media such as the Internet and 24-hour cable news networks for information.”

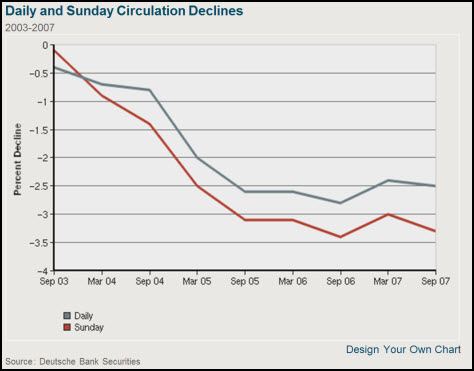

As the chart above makes clear, the downward newspaper circulation trend continues. This chart was accompanied in the report The State of the News Media 2008 with the following remarks: “Searching for… good news in the generally downward trend, at least circulation losses are not accelerating (though now advertising revenue declines are). Some of the big losers of recent years, for instance, such as the San Francisco Chronicle and the Washington Post were back closer to the industry average in circulation losses in 2007. But these are pyrrhic victories at best.”

Newspaper Circulation, Readership and Advertising

As with other periodicals where advertising is a substantial source of revenue, there is constant conflict between newspaper circulation, readership and advertising.

According to a March 2007 article by John Chisholm in Newspapers & Technology, “Benchmarks show that on average newspapers are left with around a third of their circulation revenue after costs are deducted (however) in the United States where churn levels are high and subscription rates are low, (circulation) costs can exceed revenues.”

If circulation is not the answer to the newspaper industry’s profitability, obviously advertising is, and newspaper advertising rates have traditionally been based on total readership, rather than circulation alone. The theory has more merit in the magazine industry: that more than one person might read a copy of a particular issue. The newspaper industry found gold in the concept, and with its partner-in-numbers, ABC, began to measure total newspaper readership as an adjunct to circulation.

As Bill Mitchell points out in a 2002 article on Poynter, “The good old days of 70 to 80 percent penetration, households with two parents and 2.2 kids, and a dad who came home from the factory at 4:30 to read the Evening Bulletin are long gone. Editors have been forced to take note of that growing share of audience that is on-the-fly and only sometimes attentive.”

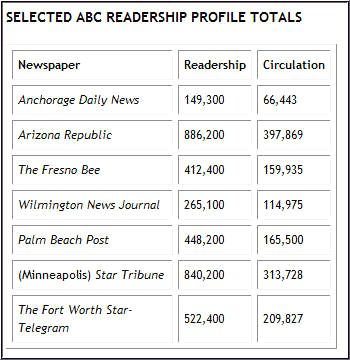

He offered the following chart to show how newspapers illustrate total readership vs. circulation (with the help of ABC):

As he correctly ponders: “Why are people passing the paper around briskly in Fresno but not so much in Louisville?”

I would argue that pass-along readership is generally overstated, and often offset by “incomplete readership” — the many who find time to look at only a portion of the newspaper, missing perhaps the bulk of the ads (or having no time to absorb the advertising message). When it comes to the newspaper industry, circulation is the more reliable figure.

Hence newspaper ad rates are increasingly focused on the latter figure, rather than on the very difficult to verify “total readership” number, particularly as the Internet makes the practice of audience measurement and response more of a science than a black art.

Going Deeper

There’s no question in my mind that the single most authoritative report on the state of journalism is The State of the News Media (not updated in 2020), published by the Project for Excellence in Journalism, a non-political, nonpartisan research institute that is part of the Pew Research Center in Washington.

Old versions can be downloaded as PDF files here.

The approach to the report is now, instead of a single massive annual study, to “roll out a series of fact sheets showcasing the most important current and historical data points for each sector – in an easy-to-digest format – a few at a time.”

Seeking Circulation Equilibrium

A fascinating and important article from The New York Times (“Why Big Newspapers Applaud Some Declines in Circulation,” October 1, 2007) puts an entirely different spin on the problems facing the future of newspapers. The lead to the article states its argument clearly: “As the newspaper industry bemoans falling circulation, major papers around the country have a surprising attitude toward a lot of potential readers: Don’t bother.” The article’s author, Richard Pérez-Peña, continues, “The big American newspapers sell about 10 percent fewer copies than they did in 2000, and while the migration of readers to the Web is usually blamed for that decline, much of it has been intentional (emphasis mine). Driven by marketing and delivery costs and pressure from advertisers, many papers have decided certain readers are not worth the expense involved in finding, serving and keeping them.

Pérez-Peña points to a trend consistent with advertising in all media: certain customers are worth reaching. But big numbers, by themselves, no longer impress. The Internet has magnified a publishing trend that probably first flowered with controlled circulation magazines: identify the customer, and deliver the right ad to the right customer at the right time in the appropriate medium.

The Newspaper Association of America is quoted in the article offering the figure that “the average cost of getting a new subscription order, including discounts, was $68 in 2006, more than twice as much as in 2002.” And most of these new subscribers disappear after the promotion ends. “So (according to Pérez-Peña) the industry is accepting that circulation will fall and hoping to find a level that can be sustained with little effort. As a result, the subscription churn rate – the number of people who drop their newspaper each year divided by the total number of subscribers — fell to 36 percent last year from 54 percent in 2000, the newspaper association says.”

The Unsteady March of Newspapers to the Web

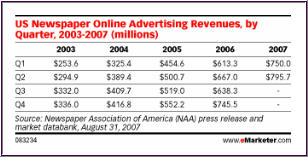

A September 2007 article in eMarketer pointed out that “The Newspaper Association of America has reported double-digit growth for the last 13 consecutive quarters of online newspaper advertising spending, which reached $795.7 million in the second quarter of 2007.”

The newspaper industry has struggled as hard as most publishing industries to find the right way to balance their traditional print product with an appropriately complementary and compelling online presence. They’ve struggled even harder to figure out how to make money from online efforts.

Newspapers succeeded most easily in the local online ad markets, but “according to Borrell Associates, (while) newspapers controlled more than 35% of all locally spent online advertising in 2006 that dominance is declining: Online newspaper share decreased 8.2 points over a two year-period.” (Reported in Editor & Publisher.) As a result newspaper companies are teaming up either with Yahoo or Google in complex cooperative deals that should benefit both sides, whether from ad revenue sharing, increased exposure or competitive positioning (both for the newspapers and the fiercely competitive search engine companies.)

Optimists increasingly feel that the newspapers companies are finally starting to “get it” when it comes to the Web, and that they’re not too late to the party. Pessimists (realists?) worry whether the very rapid decline in newspaper circulation and ad revenue can be offset sufficiently through successful Web programs.

Bright Moments

This article must read as if the news is all bad for the newspaper industry. That is not the case. There are three relatively bright spots on an otherwise gloomy horizon: free dailies, community newspapers, and looking outward toward the global newspaper industry. I’ll cover these in order.

Free Dailies

According to a well-written analysis by Heidi Dawley in Media Life (February 2007), “‘Free papers are reinvigorating the market,” says Larry Kilman, director of communications at WAN [the World Association of Newspapers]. “In many developed markets it is clear that there is a long-term decline in paid-for newspaper circulation but it is being picked up on other platforms.’

“For instance, in the U.S., the circulation of paid-for papers dropped 4 percent from 2001 to 2005, hitting 53.3 million. It also dropped 2.3 percent in 2005 compared to the year earlier.

“But that was nearly made up for by the growth of free papers, whose circulation grew by 127.9 percent over the five years, to 3.3 million copies. By 2005 free papers accounted for 5.8 percent of the U.S. newspaper market by circulation, up from 2.5 percent, according to WAN. The number of free titles grew to 34 from 19 over the period.

“Free papers saw similar growth in Europe. By 2005, free papers had grown to make up 15.3 percent of all daily newspaper circulation, up from 7.6 percent, having grown 104 percent over the period, to 16.4 million. There are now 87 free daily newspapers in Europe.

“The largest free daily in the world is Leggo in Italy, according to WAN, which has a circulation of just over 1 million. Metro in Britain follows with 977,000. The first entry for the U.S. is also Metro with a circulation of 668,000.”

Not surprisingly the news is not all rosy, particularly in the current economic downturn. A blog entry by Roy Greenslade at the UK’s Guardian newspaper called “Free newspapers feel the pinch as advertising slump takes hold,” asks if we are beginning to witness the bursting of the free newspaper bubble?

Greenslade continues: “The world’s largest publisher of freesheets, the Swedish-owned Metro International (MI), is beset by problems. It is clearly involved in a substantial retrenchment in various countries, having reported a loss of £1.5m in the second quarter this year. It is also rethinking its strategy in the United States. Clearly, the advertising downturn in America and Europe has hit the company.”

The entry concludes on a particularly downbeat note: “But frees are an interim stage between paid-for newsprint newspapers and online ‘papers.’ They will probably survive longer than paid-fors. Their main effect, however, is to convince the emerging news-reading audience that news is, or should be, freely available. Again, that leads inevitably to an online future.”

Community Papers

In the U.S. they’re often referred to as “Suburban Newspapers,” in Canada they’re called “Community Newspapers,” but either way these are the weekly papers that are published weekly in smaller communities. It’s a little confusing given that most large cities in North America also have one or two free weeklies, that fill a similar but not identical roll as the small community weeklies.

The latest data I can find on these papers paints a much healthier picture for circulation and ad sales than we find with the dailies. In June of this year the Suburban Newspapers of America (SNA) reported that “Suburban and community newspaper executives report optimism and growth. This is the finding of a beta report that included financial and other data from many of the largest members of the trade association Suburban Newspapers of America. The beta companies represent total circulation of 12.5 million and approximately $2 billion in annual advertising revenue. These newspapers provide much needed hyper-local news and information – typically not found anywhere else – to the communities that they serve.

“The beta results showed that 2007 was a growth year for the community newspaper industry with advertising revenue up .5%, as compared to the overall industry decline of 7.9% reported by the Newspaper Association of America.

“First quarter 2008 results reported a decline in advertising revenue of 2.7% – primarily related to economic factors influencing the real estate and automotive industries, two of the largest categories for community newspapers. In most cases, local revenue was up for the companies represented. This 2.7% decline for the quarter compares to double digit decreases reported by most of the publicly-traded companies that are comprised of large metro daily newspapers (reported declines ranged from 10% to 19%).”

The Canadian equivalent, Community Media Canada (now part of News Media Canada) notes first of all that not all of these papers are weeklies. 646 publish weekly; 67 twice-weekly and 29 offer three editions or more weekly. Less than 50% charge for subscriptions. Data in CMC’s Snapshot 2007 indicated strength in the industry: “Community newspapers are a growing medium across Canada. As circulation at daily newspapers declines, community newspapers are growing, since they maintain their monopoly on truly local content. This fact has not gone unnoticed by major corporate stakeholders…. Recent data shows that advertising in community newspapers exceeds $1 billion annually. Revenue from flyer distribution — a closely aligned sector — is also on the rise. In fact, since 2000, industry revenue has increased 26 per cent.”

The Global Newspaper Industry

In the midst of this gloom, the February 15, 2007 issue of The Economist reported that in India there are some 300 big newspapers, and they experienced a 12.9% increase in circulation that year. Indian government figures shows growth of newspaper and periodical titles at nearly 50% from 2001 to 2010. The publications are in 16 different languages, with Hindi the number one language and English number two. Newspaper competition is fierce, and the profits are substantial. A 2016 update can be found here.

I remember some 15-years years ago at the drupa trade show in Germany (drupa focuses on the printing business) meeting Naresh Khanna, then the publisher and editor of Indian Printer & Publisher magazine. That year everyone was speculating about the possible impact of the Internet, but Naresh said to me: “Oh, we don’t care very much about the Internet in India. We’re just excited that we’ll soon have color pictures in our newspapers.”

The global newspaper industry is continuing to grow because of emerging economies like those of India and China, even while the future of the newspaper industry is seriously threatened in the mature (largely Western) countries.

The best source for data on world newspaper trends is the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers which groups “76 national newspaper associations, individual newspaper executives in 102 nations, 10 news agencies, and 10 regional press organisations. It is a non-profit, non-government organisation. In all, the Association represents more than 18,000 publications on five continents.” The PDF executive summary of its “World Digital Media Trends 2008” provides data showing that simply focusing on the North American newspaper market is not indicative of the state of newspaper publishing around the world.

Conclusion

There appears to be very little doubt that newspapers in the United States are facing the greatest threat in their history. The numbers grow more grim with each new report. Does the United States truly represent the future of the newspaper industry, or might the specific conditions here be anomalous? I believe they do actually represent the shape of things to come, hence my very negative rating at the start of this article.

But the story is far from over. It’s a fascinating ride.

Some Additional References

1. Three fine publications:

And the Canadian Ryerson Review of Journalism.

2. Bob Sacks, aka BoSacks, a learned veteran of the American media industry, has a very good website, and, if you can digest three entries per day, you can subscribe to his essential industry newsletter.

3. The Neiman Journalism Lab at Harvard is the cat’s pajamas: a fascinating exploration and reference, or as the site states: “a collaborative attempt to figure out how quality journalism can survive and thrive in the Internet age.”