March 15, 2018

- The printing industry is supported by one major U.S. trade association, the Printing Industries of America (PIA). The PIA has a great set of online resources (some member-only).

- The key UK printing industry association is the British Printing Industries Federation (BPif)

- The Canadian Printing Industries Association (CPIA) is a member of the Canadian Manufacturing Coalition.

- There are two key U.S. trade magazines/sites, Printing Impressions and WhatTheyThink. In Canada it’s PrintAction.

- My blog posts that look at the printing industry include:

- As the Printing Industry Burns (a look at Cenveo’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy)

- Let’s Check in with the Printing Industry (2009)

- My older columns from Printing Impressions are here.

The Elevator Pitch for the Future of Printing

1. A large portion of available information (and entertainment) is printed. Still. Newspapers, books, magazines, brochures, direct mail, and many more. There are certainly far more new pages on the web each day, but print is still a dominant force.

2. The printing industry has not been ignoring the changes that surround it. The technology of print is in a state of constant innovation. It has never been cheaper and faster to get a high-quality publication (of any sort) to the reading public.

3. At the same time print publishing is now assaulted from multiple angles. Paper prices are up. Postal rates are up. And the reading public is increasingly distracted by other media: the Internet, television, computer games, mobile devices and more.

4. The economic analyses surrounding the health of the printing industry are as contradictory as they are for most other industries covered on this site. There’s bad news, and there’s good news. My overall read of the figures is not positive; at the same time the industry is apparently not in freefall.

5. The future success of the printing industry is very closely tied into the shifts in advertising spend. (This section should be read in conjunction with the section on advertising.) Those trends show a clear move away from print as a primary medium for ad dollars. With its huge reliance on advertising-supported printing, it’s difficult to see how the industry will be able to transition to wean itself of that essential source.

6. Like many other industries covered here, the print industry is in the midst of substantial consolidation, removing capacity so as to shore up prices. At the same time, new print technologies are adding capacity roughly as quickly as consolidation removes it, and the net is likely a wash.

Page Index

- Summary of the Future of Printing

- Printing is a Diverse Industry

- The Impact of Internet Advertising on Printing

- Is Printing a Zero-Sum Game?

- Which Half?

- Advertising Drives the Future of Print

- It’s Not a New Story

- What’s a Printer to Do?

Summary of the Future of Printing

We’ve reached a time for a vote: does printed matter matter to us more than the Web? The jury is out, because instead of twelve jurors we’ve got millions, of all ages and demographic backgrounds. As you can read in the section on Social Demographic Issues, the answers vary widely.

Regardless, there’s no doubt that printed matter matters. I’ve been very tempted to pose a challenge on this site: who ever ACTUALLY SAID that print is dead? Print is so far from dead that the (too-often-repeated) comment draws doubt to its authenticity.

Print is very much alive, and, I guarantee you, will outlive anyone reading on this Web site.

The questions of course are what form printing will take, how the industry will evolve, and what consumers will do in the face of the enormous change in media choices.

Printing is a Diverse Industry

No analysis of print is worth its weight in print without recognition of the tremendously diverse range of activities that comprise “printing.” The result is that while, for example, newspaper printing may be taking a steep hit, direct mail advertising continues to grow.

Source: Frank Romano via prepressure.com

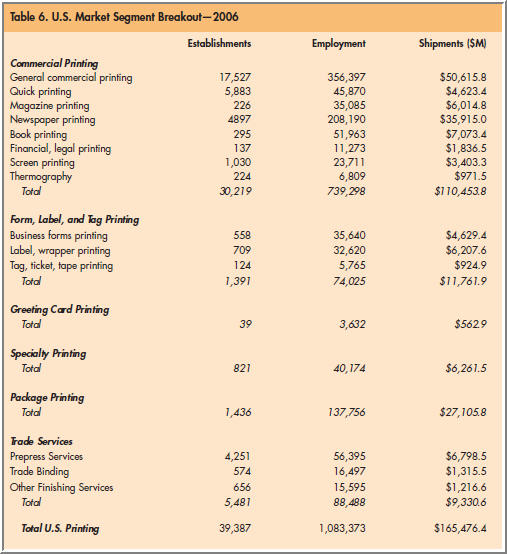

Magazine publishing may be challenged, but magazine printing represents only 3.6% of total U.S. print sales. Worried about the shift of financial and legal printing towards online publication? This category represents only 1% of print sales.

Nonetheless, most industry observers agree that the print market is driven by advertising more than any other force, and that is a source of concern.

The Impact of Internet Advertising on Printing

When I recently searched Google for “printing” I was offered three pages of sponsored links, including “Who’s Your Print Daddy? – Printing that looks like a million bucks, but costs like .03 cents” Clicking on the URL I learned that “With presses in Texas, California and Florida, we can deliver high quality product nationwide for a fraction of the cost anywhere else! Our mission is simple: To give our customers the greatest return on their investment with service and quality that is unmatched. Highest Quality – Lowest Prices – Guaranteed.”

For an old print buyer like myself it all sounded a trifle suspect. But for the average Joe, not sophisticated in the ways of print procurement, it could sound pretty appealing.

More importantly, I think, how else would DallasPrinting ever reach a worldwide market for its services? Could it effectively advertise across North America on television or radio? What magazine would offer a profitable return on its advertising investment?

Still, what’s most important about DallasPrinting’s Google ad is that DallasPrinting.com pays only for those who “click through” to its website. Sure, not all of them will be buyers. But a substantial percentage probably will be – otherwise they wouldn’t click on the link. And further, if DallasPrinting finds that the click-throughs aren’t leading to real orders, it can quickly pull its ad from Google and try it somewhere else. Or it can stay with Google and perhaps switch the listing just to people searching for “low-cost printing,” or to “printing in Dallas.”

Welcome to the new age of advertising. It’s not for the masses, it’s for individuals. It’s about the often-rumored and too-often-discussed one-to-one marketers: advertisers who believe that it’s possible to reach out directly to individuals, rather than just throwing up billboards for the masses.

Who are the blind who will not see? Everyone involved in traditional advertising, whether buyer or seller, who refuses to look closely at the changes taking place in advertising and fails to determine a counter-strategy. Printers are probably no more guilty of this blindness than television networks and newspaper and magazine publishers. But the change is accelerating, dramatically so, and the required adjustments are neither obvious nor simple to put in place.

Is Printing a Zero-Sum Game?

To understand the impact of Internet advertising on print (and other media) it’s very important to recognize Thad’s “Law of Shifting Ad Budgets,” a.k.a. “Thad’s Zero-Sum Game.” When a new advertising medium becomes popular, be it cable television or the Internet, marketers do not augment their existing advertising budgets to accommodate the new medium. Instead they subtract dollars from existing advertising media to accommodate the shift.

Clearly the advertising-to-sales ratios of different industries vary greatly. What they do not do is vary according to available media. The percentages are determined based on optimal advertising expenditures against sales revenues, not against the availability of media on which funds can be expended.

While it’s conceivable that an advertiser would decide to retain all of its existing ad campaigns and supplement those expenditures with an Internet spend, simple logic makes it obvious that a prudent marketer would look to reduce expenditures in one medium if another, such as the Internet, was delivering a better ROI.

Which Half?

I know that half of my advertising budget is wasted, but I’m not sure which half.

—Lord Leverhulme, date unknown

Nothing has so much characterized the modern advertising era as the too-often-mentioned quotation above. What should a marketing executive boast after committing hundreds of millions of dollars to network television advertising (or to a single advertisement during the Super Bowl)? Sales are up; an impact was achieved. But how to measure an ROI on the campaign? Impossible.

The essential difference between Internet advertising and all other forms of advertising (including, of course, print in periodicals) is that the results are measurable. OK, not 100% measurable. But compared to any type of mass-market advertising, the Internet is like a smart bomb.

Direct mail marketing is the closest thing that print offers to compete with the Internet. It’s direct and it’s measurable. But sadly it tends to measure responses rates below 5%, while targeted Internet advertising dwarves that number, not simply in overall response rates, but, far more importantly, in cost per response. (It’s significant that the fastest growing sector in print today is direct mail powered by variable data. When used well, response rates rise enormously. Clearly this can be cost-effective advertising, even more so when used as part of an integrated marketing campaign with a strong Web component.)

Advertising Drives the Future of Print

Make no mistake about it: advertising is the engine the drives most print expenditures. According to the PIA’s Ronnie Davis, advertising drives nearly 45% of print spending, dwarfing its nearest competitor, “wholesale trade,” just below 10%.

If the Internet is siphoning off ad dollars from network television, it’s also taking money away from print.

It’s Not a New Story

As reported in Pira’s Future of Print (by John Birkenshaw and Peter Hart, © 2000), based on data from Zenith Media, the percentage of the total ad dollar marketshare enjoyed by print has been declining slowly but surely since 1990.

On June 6th the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) and PricewaterhouseCoopers announced that Internet advertising totaled over $2.8 billion for the first quarter of 2005, a 26% increase over Q1 2004 ($2.2 billion) and a 4.3% increase over Q4 2004 ($2.7 billion).

Magazine ad revenue will total some $18 billion in 2006. The Internet won’t be all that far behind. More importantly, it will be gaining fast.

What’s a Printer to Do?

As Jonah Bloom, as executive editor of Advertising Age (the bible of the ad industry) pointed out in his July 25, 2007 column in AdAge.com: “…few seem to have integrated their Web operations with the rest of their marketing. In most marketing departments or agencies, the folks who evaluate and buy keywords or optimize search engines sit in a separate silo from the rest of the ad or marketing team…”

This is the problem that besets printers just as drastically.

Every printer must be tired by now of the lecture that starts: “Stop calling yourself a printer: you’re a graphic communicator.” But as the quote above reveals, it’s not only printers that find themselves myopically pigeonholed. The customers of printing companies are increasingly looking to integrated marketing across multiple channels. Can printers command the shift, or will they be left collecting shekels in its wake?

References

For more references, see at top of page.

1. Associations

Printing Industries of America (the merged PIA and Graphic Arts Technical Foundation (GATF)) is the great source for the printing industry, followed closely by the National Association for Printing Leadership (NAPL) (after it’s merger with the quick print association). (2017 update: NAPL merged with Association of Marketing Service Providers (AMSP) and rebranded as Epicomm, which in 2016 merged with Idealliance, “an association of brand owners, agencies, publishers, printers, mailers, distributors, and their materials and technology providers.”

2. A Good Book and It’s Free

Disrupting the Future, by Dr. Joe Webb and Richard Romano is an essential resource for anyone trying to understand what makes the printing industry tick. It’s described as “a contrarian look at the printing industry and the new rules and strategies needed to succeed.”

The following is an article I wrote in January 2002, but not published at the time. I’m adding it here because it makes a point that I think applies more broadly to the impact of recessions on entertainment industries, namely that underlying technology trends can be accelerated by broader economic forces.

The Recession and the Printing Business

Written January 30, 2002

Like just about everyone in business in the U.S., I’ve been following the economy closely. Last fall I was waiting for the recession to be announced, and soon after wondering when it would end. At the same time I’ve continued to follow the Internet and the Web, and watched them move through the painful collapse of the speculative investment bubble. At first glance these two pursuits appeared unrelated, but now I think that they reveal some clues about the future direction of the print industry.

In the December 3rd edition of “News, Inc.“, David Cole’s newsletter devoted to “the business of the newspaper business,” the cover story is headlined “October Revenue Figures, New Cuts, Confirm Recession.”

The article describes a slew of recent negative earnings reports from major newspaper companies. It quotes Anthony Ridder, CEO of Knight Ridder, as saying “Economists may debate whether we are in a recession as they classically define it, but for those of us in the business of publishing newspapers, this is the real thing.” He made this statement last April. It wasn’t until November last year that the National Bureau of Economic Research declared the recession real. (Although they then admitted that it had started last March.)

Printers could have told the Bureau about the recession. Most companies were feeling it all year.

American economists, analysts and businesspeople are nothing if not optimistic. Give them a piece of bad economic news, and they’ll reply with an upbeat forecast. Talk about a recession, and they’ll talk about the end of the recession, and the prospects for a speedy recovery. In the December issue of Printing Impressions, Ronnie Davis, the chief economist at the Printing Industries of America (PIA) wrote, “recovery should begin in the first half of 2002. The current updated consensus outlook is for the economy to rebound to positive growth in the first quarter of 2002 and get back to an annual growth rate of 3 percent by the second quarter.”

I’m all for optimism. It helps us through tough times. But it can leave us unprepared when the underlying situation, rather than improving, takes a turn for the worse. I think that there’s a high probability that the U.S. economy is going to get worse before it gets better. Perhaps even more serious, I believe that even when the economy starts to show clear signs of improving, the printing business will remain largely flat. There will be some improvement in a few categories, such as packaging, but I think that general commercial, direct marketing, magazines/periodicals, catalogs and books will fail to rebound significantly after this recession ends, and will in fact show continuing declines.

The reason that things may get worse before they get better is straightforward: there are enough remaining uncertainties in the markets, and in the world, to cause further significant financial deterioration. As I write this column in late January, these uncertainties include:

1. The impact of the collapse of Enron.

2. The collapse of the Argentinean economy.

3. The inconclusive finish to the war in Afghanistan.

4. The deteriorating situation between Israel and the Palestinians.

5. Instability in oil pricing – prices are low; suppliers are nervous.

6. Japan’s continuing economic woes threatening to spill over into the rest of Asia.

One or more of these scenarios could play out to have a negative impact on the weakened U.S. economy. With so many simultaneous points of instability, the risk is unusually high.

In the best scenario, none of these situations will spiral out of control, the recession will die a natural death some time in 2002, and recovery will begin. Why then won’t the printing business march alongside that recovery? A simple answer: the Internet and the Web.

According to Nielsen/NetRatings, U.S. Internet usage in October set a new record, with 115.2 million users, up 4% from September, and up 15% over October 2000. Each user was online for an average of 19 hours over 35 sessions, a 9% increase in time spent over October 2000.

I found more detail about the impact of the Internet on publishing last November at the e-Content show, held in Santa Clara, CA. A variety of presentations explored the nascent but growing markets for Web-based content.

Rick Miller from the Copyright Clearance Center looked at the growth in Web usage from an unusual angle: the shift from photocopying to downloading. While 53% of people aged 55 or older have photocopied content for personal use, only 13% of this group have downloaded content from the Web. Contrast that with the under-25-year-olds. Only 20% have photocopied content, while 40% have downloaded it. Half of the older group say they are getting more information through photocopying than ever before, while 80% of the under-25s agree with the statement “I am obtaining fewer copies from photocopying, and more via electronic media.”

A presentation by Gary Grenier of IEEE (The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), a large non-profit technical association, looked at the steady shift from print to electronic publishing within his organization. IEEE annually publishes over 100 journals and magazines, 800 standards and 350 conference proceedings, for a total of 70,000 articles a year. Until 1991, 100% of publishing revenue was derived from print subscriptions. By 2001, revenue from online subscriptions had moved ahead of print.

While several of the conference presentations acknowledged that online advertising is, at best, in a slump, most argued that revenue growth will resume as Web publishers learn to move beyond the banner ad.

Scott Moore, publisher of the successful Web news and commentary site Slate, pointed out that the site gained only 26,000 subscribers when it charged $19.95/year. Since dropping the subscription charge, and moving to an ad-based model, Slate has reached #7 in the Top Ten Online News Sites, with an audience approaching 5 million. Ad revenues have hit “the mid seven figures.” Moore pointed out that each new medium takes time to mature. While the Web now comprises 12% of total U.S. media consumption, it’s drawing only 3% of ad budgets. The Web, he argues, is well poised against print periodicals because, like TV and radio, increasing audiences adds few additional costs, while fattening ad ratesheets.

There’s the rub. The Web is inherently a more efficient communication medium than print. When economic times were good, marketers experimented with the Web, but could afford to remain committed to print, from their perspective a safe bet. This recession forces print buyers and advertisers to cut costs, and search for the most economical ways to get their messages to the market. They’re strongly encouraged to maximize their use of the Web, if only for economic reasons. A prolonged recession will further encourage this trend.

The recent anthrax attacks have highlighted another of print’s weaknesses. At the same time, a new generation of consumers is coming into the marketplace more comfortable with the Web than with print.

The inevitable eventual return to economic good times should loosen a few purse strings, but it won’t make print more cost-effective than the Internet. Of course print will continue to play a key role in the communications mix. But I think that print’s glory days have passed, unfortunately accelerated by the current recession. And I don’t think that many printers are ready to admit this to themselves, their employees or their investors. If I’m right about these trends, smart printers should make moves now to shore up and diversify their businesses. If I’m wrong, smart printing companies will just be that much stronger than their competitors.