Updated September 9, 2021

My new format for these topics is to provide links to industry data sources that can help YOU make some educated guesses about where, in this case, book publishing is headed. Here goes:

Sources:

- This is an industry with a history and a tradition. Since 1872 the “bible” of the American book publishing industry has been Publishers Weekly. Most of what you need is online, but a subscription is valuable for the dedicated observer.

- The bible of the UK book publishing industry (since 1858!) is The Bookseller. They keep even more content behind the firewall than Publishers Weekly. Subscriptions cost north of $200 (£156).

- The bible of the Canadian book publishing industry (since 1935!) is Quill & Quire. Subscriptions here ($180 Canadian dollars).

- Devoted North American trade industry observers also subscribe to Publishers Marketplace. Editor Michael Cader understands the business of the book business better than any other publishing industry reporters, keeps track of rights sales, and has a great directory of industry players. Annual “membership” subscriptions are $275.

- Next up is tracking the industry associations. They offer very inconsistent quantities of data. But you need to know the ones that matter. The voice of the biggest players in the U.S. is the Association of American Publishers (AAP). (Membership price on request.)

- Small publishers sometimes join the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA). IBPA is far more hands-on than the AAP; members get access to the good stuff they publish and report (starting at $139 per year). The IBPA is also, increasingly, the voice for professional self publishers.

- The Book Industry Study Group (BISG) helps set standards, and supports research and events via working groups and committees. There’s some good analysis available, and great networking opportunities, but membership is pricey (starting at $636 a year) for some individual industry observers (but is essential to publishers and to consultants, like myself).

- My blog post on the three top self-publishing industry analysts is here. Jane Friedman, Joanna Penn are must-reads. Jane’s newsletter, The Hot Sheet, is an excellent resource both for authors and publishers ($59/year).

- Two of my favorite no-cost industry blogs/newsletters: Ken Whyte’s SHuSH, and Publishing Trends’ Top 5 Publishing Articles/Blog Posts of the Week.

The Elevator Pitch for the Future of Book Publishing

- I updated this article in fall, 2021, from a piece first published in 2013. Some of the data is dated, but I’ve left it in place where it’s illuminating.

- According to a 2014 report from Bowker, the book publishing industry bible, the number of titles self-published in 2013 increased to more than 458,564. Head over to Amazon.com’s home page for books and look down the left column. Click “New releases –> last 90 days” and marvel at the number. It’s “over 1,000,000” as I write this in February 2018; last 30 days it’s “over 500,000”! (September 9/21 update: Amazon, ever protective of sharing useful data with an industry it dominates, has discontinued public access to these numbers.)

- Nielsen BookScan, quoted in the June 2007 Harper’s magazine (subscribers only), reported that nearly 1.5 million different titles were sold in the United States in 2006, although 78% of those titles sold fewer than 99 copies, while only 483 titles sold more than 100,000 copies.

- A ground-breaking 2005 report (no longer online) by the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) revealed that there were 62,815 active publishers in the United States, and that 46,860 of these publishers had revenues below $50,000 per year. (Most observers would have placed the number well below 5,000; in 2002 the U.S. Census reported 3,570 book publishers.) In 2006, using a slightly different methodology, the BISG reported that there were in fact 88,528 “active” publishers in the U.S.—nearly 68,000 had sales under $50,000 per year (no longer online).

- With all of the demographic changes in print readership, the book publishing industry has weathered the challenge, in part through the publication of more specialized titles in shorter print runs, in part through increased publication of “non-books” (novelty titles) and in part through improved distribution, including via the web.

- In the separate section on Education I cover the textbook industry. Growth has stalled, profits are plunging. The largest publishers are moving their content into digital-only versions that students can access via an “all you can eat” model.

- Despite some modestly positive trends, the underlying basis for a successful future for the book publishing industry is rapidly being eroded. As reported below, reading rates are dropping, and average annual household spending on books dropped 14% between 1985 and 2005, adjusted for inflation.

- Audiobooks are a thriving part the industry, both substituting for and augmenting print sales. Ebook sales leveled out in the 15-25% range for most publishers, and represent an important, profitable market.

- COVID has proved a boon to book publishing during 2020 and 2021. It remains to be seen how many of these sales gains can be sustained over time. Fingers crossed! (2022 update: Sales are down 4.1% to July, 2022, but still up from pre-Covid levels.)

My overall rating for the future of book publishing is a continuing modest decline in total sales volume, but certainly not an impending catastrophe.

Page Index

- Overview of the Future of Book Publishing

- The Traditional Context of Book Publishing

- Types of Book Publishing

- The Scope of the Book Publishing Business in North America & Worldwide

- The Practice of Book Publishing

- Print-on-Demand Changes the Equation

- Vanity Publishing Becomes Self-Publishing

- Book Readership

- Future of Book Publishing — Trends & Outlook

Overview of the Future of Book Publishing

What is it about books that make them the sine qua non of publishing? I think it’s very simple. Great books have changed lives, have changed history. While there have been innumerable articles of great importance in magazines and newspapers, let’s face it – they don’t have the force of the classics of literature and non-fiction. Just about any reader can point to a book that has changed his or her life. Most of us can point to many different books that have had an equally strong impact.

We encounter these books at different ages. I know that many of the books I read when I was only 10- or 12-years-old made a huge impact then and still influence me today. The whole context of reading as a child was a unique emotional experience. As I grew older, I found books that suited my age, and continued to grow and mature with the extraordinary literature at my disposal.

Further, since Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropic efforts, there has always been a great infrastructure for enjoying books. Most cities in North America have many fine libraries and bookstores. Books are everywhere! Supporting them also was a robust film industry that interpreted books in unexpected ways; as often as not driving us back to the original written version.

I fully entered the world of books in the early 1970s via book publishing, first as a bookseller, then as a traveling book sales rep, and then as a publisher. I still have very strong feelings about book publishing: most of the people I know who work in the book publishing industry feel as strongly. It’s hard to get publishing out of your blood.

Book publishing is not the first form of publishing by any means – think cave drawings, scrolls and those dedicated monks with their beautiful manuscripts. But somehow book publishing has come to embody the idea of publishing more than any other form—when I say “publishing” you probably think books (perhaps even if you happen to be a newspaper publisher).

Yes, for most of us, books hold a unique emotional place in our hearts and minds. When it comes to imagine the so-called “death of print,” we react in unison: Perhaps some kinds of print, but not books!

So then how to interpret the changes in the book publishing industry? We’ve still got Harry Potter, don’t we? (With the last volume the greatest success of the series.)

What about all of the books for children, those marvelous classics. Surely they won’t disappear? The bestsellers we read in hardcover and paperback; the fine non-fiction biographies and histories. These can’t disappear, can they?

The Traditional Context of Book Publishing

Nearly all of us who are close to printing and publishing romanticize Gutenberg’s invention of movable type (circa 1450) and cheerfully ignore the context that surrounded it. We cheerfully ignore the fact that printing was invented in China long before Gutenberg got near his printing press, and that in Korea a system of printing from movable metal type was developed around 1041.

We ignore that Gutenberg was a businessman as much as he was an “artist” – and possibly much more interested in business than art. (Unfortunately he was not a stellar businessman – by 1455 Gutenberg was effectively bankrupt.)

Not surprisingly, the history of publishing is well-documented in books. One such, a fine work, The Nature of the Book by Adrian Johns (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1998), illustrates in 753 pages the very commercial nature of the book trade from its earliest days. Book publishing today is very much a descendant of those early efforts. It remains inescapably a commercial enterprise.

Certainly some not-for-profit groups, associations and government-subsidized efforts reduce the commercial pressure on their publication efforts as money-making ventures. But the vast majority of book publishers worldwide undertake their tasks with at least one eye on the bottom line, and this necessarily has a great impact on how the business of book publishing is conducted.

As someone who operated three different trade publishing companies in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, I began to see the modern challenge of book publishing as two-fold. The first was to get anyone to notice that a new book had even been published – as we’ve seen, hundreds of thousands of books are published each year, and it is expensive to get noticed with that much competition. Also (and particularly in the pre-Internet era), the sale of trade books relied on the distribution of those books to bookstores across America, or across Canada, or across…you name the country, and the cost of this broad geographic distribution was prohibitive except for the most high-profile titles. (Which tended to push publishers toward paying large advances for the few titles that were hoped to carry the many.)

I’ll examine shortly the statistics that bear on these challenges. Some of them have changed in the last decades; many still apply.

Much more interesting to consider is the impact of the Internet on the creation, marketing, distribution and sale of books. The Internet is having an enormous impact on the future of book publishing – both in positive and negative ways. I’ll examine this trend also.

At the same time there are other forces at work: eBooks, print-on-demand, the digital scanning of vast libraries and the conversion of certain books into other electronic formats. Each of these is playing a part in securing a fascinating future for my beloved The Wind in the Willows. Technology need not be destructive for book publishers; it can be a very positive force for change.

Types of Book Publishing

There are many kinds of book publishing. Most listings differ, but here is a representative sample of publishing types.

1. Trade publishing

(i) Hardcover

(ii) Trade paperback

(iii) Mass-market paperback

(iv) Children’s books

(v) Religious books

2. Textbook publishing

(i) Textbooks in hardcover or paperback

(a) K-12 textbooks

(b) Secondary school textbooks

(c) Higher education: college and university textbooks

(d) Post formal institutional education (adult learning) textbooks

(ii) Ancillary texts, such as teacher or student guides

3. Reference publishing

(i) Encyclopedias

(ii) Directories

(iii) And numerous others

4. Reports, studies, etc. by not-for-profit publishers, government agencies, etc.

No discussion of book publishing can be authoritative without recognizing its varied species.

Bill Kasdorf’s classification is more precise, “a handy reference to the various ways publishers of books and journals are classified.” He points out that many of the classifications overlap. Kasdorf notes four main types of publisher:

- Trade publishers

- Scholarly publishers

- Educational publishers

- Reference publishers

… although reference publishers don’t always publish in either book or journal form. Read his complete post for more.

The Scope of the Book Publishing Business in North America & Worldwide

A circa-2000 report from Hoovers offered a quick overview of the U.S. publishing industry. Many of the names and faces have changed, but the overall forces are still at work: “The US book publishing industry consists of about 2,700 companies with combined annual revenue of $25 billion. Large US publishers include McGraw-Hill, Pearson PLC, John Wiley & Sons, and Scholastic. Some of the biggest publishers are units of large media companies, including HarperCollins (NewsCorp), Random House (Bertelsmann AG of Germany), and Simon & Schuster (CBS Corp). The industry is highly concentrated; the top 50 companies hold 80 percent of the market.” This book industry report points to two different aspects of the industry: first, that there is a high degree of concentration at the top of the pyramid, and two, that most book publishing analysts grossly underestimate the size of the industry in the U.S. As pointed out above the Book Industry Study Group claims that in 2006 there were in fact 88,528 “active” publishers in the U.S., and nearly 68,000 had sales under $50,000 per year.

AAP latest U.S. book sales estimates can be found at the link above.

An article in Wikipedia entitled “Books published per country per year,” covers 127 countries, quotes from various statistical sources (not all of them current), and estimates that some 2,210,000 million titles are published annually worldwide (this based on UNESCO data).

One figure for worldwide book sales was from John Kremer, who wrote, “In 1995, world book sales reached $80 billion. Worldwide book sales are expected to hit $90 billion by the year 2000.” As Kremer states that U.S. books sales were $25.5 billion in 1995, then the ratio of U.S.-to-worldwide sales was about 1:3. I would expect the ratio has increased somewhat in the last 12 years, and so using BISG’s 2008 U.S. sales figure of roughly $40 billion, worldwide book sales should be in the $135-$150 billion range.

The Canadian Government’s Statistics Canada agency counted 1,324 publishing companies in 2005, representing total sales of (CDN) $2.4 billion. It cautioned however that “the number of establishments is comprised mainly of small companies. Of the 1324 establishments for the industry only 444 were in the survey portion. This means that most of the movement in number of establishments from year to year comes from 884 companies that had under $50,000 in revenue.”

Based on the U.S. figure of over 62,000 active publishers, one wonders if the Canadian figure should not be closer to 6,000 than 1,000, judging by the standard 10 to 1 ratio that holds for most industrial comparisons between the two countries. Canadian Books in Print listed 4,300 book publishers in the year 2000.

According to an article by Philip Cercone in the magazine Policy Options (PDF) “The book industry in Canada is concentrated in Ontario, whose firms publish almost entirely in the English language, and Quebec, whose companies publish principally in the other official language. These two provinces account for over 90 percent of industry operating revenues and 95 percent of industry operating profits.”

A unique aspect of the Canadian book publishing market is that 19 foreign-controlled publishers, which represented less than 6% of all companies surveyed, accounted for 59% of domestic book sales in 2004 (the percentage has increased). The Canadian book publishing industry is foreign-dominated. As Cercone notes, “Book publishing in Canada is not in the hands of, or controlled by Canadian-owned companies, but is in those of a very few profitable foreign-controlled book publishers. These multinational companies tend to publish in large part the more established and better-selling authors, while the Canadian-owned companies tend to act in many instances as ‘farm teams’ to them. Canadian-owned publishing companies tend to publish in the less lucrative genres and predominantly publish first time Canadian authors.”

Hoovers also remind us that “demand for books…is largely resistant to economic cycles.” As I discuss in my 2008 blog entry “Economics and the Future of Publishing,” this recession is thus far proving different, and the eventual outcome for book publishers remains to be seen.

Publishing Trade Associations

The Association of American Publishers is the major trade group representing “America’s premier publishers of high-quality entertainment, education, scientific and professional content – dedicating the creative, intellectual and financial investments to bring great ideas to life.” It has 300 members and so is representative of mainly the largest publishers.

Next up is the Independent Book Publishers Association serving some four thousand smaller book publishers.

In Canada, the the Association of Canadian Publishers is “the national collective voice of English-language Canadian-owned book publishers”, representing 135 Canadian-owned and controlled book publishers from across the country. The Literary Press Group of Canada represents about 60 Canadian literary book publishers. The Canadian Publishers’ Council represents the 18 largest publishers, primarily the large foreign-owned subsidiaries, that “collectively account for nearly three-quarters of all domestic sales of English-language books.”

Christian publishers have a couple of associations, as do other specialized publishers.

The Practice of Book Publishing

Several unique practices have definitively characterized book publishing in the modern era:

1. Individual editors and/or publishers make individual decisions about what will or won’t be published by their firm (at larger companies, a larger group may be involved in the decision).

This, as much as anything I believe is the cause of the transformation and decline of book publishing in the modern era. Who are these editors and publishers who have so much power to make life-and-death decisions on what books will or won’t be published each year? They may have some kind of education associated with the history and/or practice of writing and literature. This ostensibly makes them “expert” in what constitutes “quality” in writing. But of course they are as susceptible as the rest of us to individual matters of taste, to bias and to lapses in judgment. Still their role within their respective companies is god-like – they make judgments of life or death, except in this case upon what will be published, rather than who will be sent to hell.

Furthermore, at the largest book publishers the decision is no longer generally about quality but more often about salability. Is that taught at Swarthmore?

Publishing courses are now abundant. Who really believes that you can take English majors in their twenties and “teach” them how to intuit what will be this year’s bestseller? Twaddle.

2. At the same time, I consider it inarguable that most writers need good editors. William Zinsser, author of the classic text On Writing Well, wrote “The essence of writing is rewriting.”

Ernest Hemingway is reputed to have told George Plimpton during an interview that he rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms 39 times before he was satisfied.

“Why so many rewrites?” Plimpton asked.

“Because,” Hemingway responded, “I wanted to get the words right.”

So while I argue above that editors can offer blocks to the publication of worthwhile books, in their key role, that of helping authors improve their texts, they are invaluable. That has been my consistent experience. The tales of great editors are legion, such as Maxwell Perkins and his role in shaping F. Scott Fitzgerald’s prose. But a merely good editor can work magic also.

While many very poorly-written and poorly-edited books have become bestsellers, this doesn’t obviate the general rule: a book written (and/or edited) with clarity in mind will succeed beyond a similar text that lacks such clarity.

3. The book industry has traditionally been a retail-based industry. Books are mostly bought in bookstores. The explosive growth of the major chain booksellers in the 1970s and onwards was continually lamented as representing some sort of “death of publishing.” That dire prediction on the future of book publishing proved untrue. The major complaint was that the book chains would force publishers to take a pass on publishing important books in favor of “mindless” bestsellers. But with 350,000 books published in English last year that prediction has also proved false. Furthermore the numerous book superstores ordinarily feature a far broader inventory that the average independent bookseller.

Online bookselling by Amazon.com and its competitors has had an enormous impact on bookselling. Now anyone can quite easily obtain any of the 300,000+ new books that can’t be found in the retail channel. The result is that never have so many different books been so easily, readily and inexpensively available.

Print-on-Demand Changes the Equation

The improvement in print-on-demand (using a generic name for this type of print manufacturing) over the last two decades has been astounding. As discussed elsewhere, most book publishers grew up in an industry where the consideration was between printing 3,000 copies or 5,000, hoping to shave perhaps 10-15% off the manufactured cost. What happens when you can print one book for 120%/per unit of the price of 3,000 books? An industry changes.

Vanity Publishing Becomes Self-Publishing

Vanity publishing always had a bad name. The concept was that some sucker would pay some huckster to print several thousand copies of their “terrifically important” manuscript that somehow had been cruelly overlooked by 300 New York agents and publishers, and turn that into the bestseller it had always deserved to be. Of course there were a few success stories to fuel the flames, but in many cases naïve authors found themselves with a large invoice and 2,999 copies of their book in the bedroom cupboard.

The big difference is distribution. In the old days of vanity publishing, those publishers had few mechanisms for book distribution, and even fewer chances of having their vanity publications taken seriously by any of the mainstream book reviewers.

In the age of the Internet, distribution issues are significantly muted, and the reading public has discovered that they don’t necessarily care what The New York Times says about an inexpensive book covering a topic in which they’re interested.

This has led to the blossoming of Lulu.com and its many brethren (see References for more information on Lulu.com), and I for one, will not lament the end of New York’s hegemony on deciding what should be purchased and read.

For more information on the phenomenal growth of the self-publishing industry, see my blog entry: More Data on the Number of On-demand Titles in 2008.

Book Readership

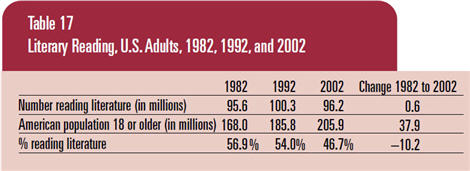

One of the most important documents illuminating key aspects of the future of book publishing is a 60-page report published by in June 2004 by the National Endowment for the Arts. Called Reading at Risk, the report presents the results from a 2002 survey (conducted by the Census Bureau) of 17,000 people aged 18 or older, who attended artistic performances, visited museums, watched broadcasts of arts programs, or read literature. The results are compared to similar surveys carried out in 1982 and 1992. The first sentence of the preface to the report notes that “Reading at Risk is not a report that the National Endowment for the Arts is happy to issue.”

The survey asked respondents if during the previous twelve months they had read any novels, short stories, plays, or poetry in their leisure time (not for work or school). As the report notes, included were “popular genres such as mysteries, as well as contemporary and classic literary fiction. No distinctions were drawn on the quality of literary works.” Literary non-fiction was apparently not included.

The results paint a grim picture for the future of the book. The charts (all taken directly from the report, and copyright of the National Endowment for the Arts) best reveal the tale:

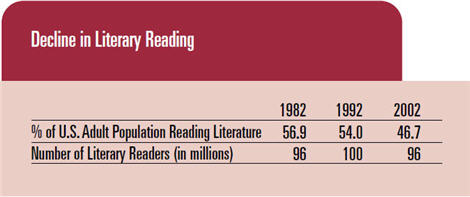

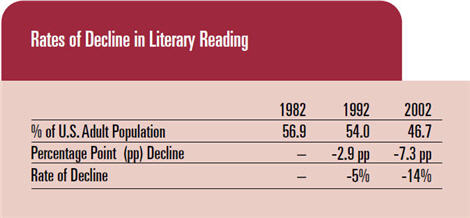

What is most notable in this first chart is an important anomaly between the number of literary readers and the percentage. Because of population increases, the total number of readers is constant over a 20-year period, while the percentage decline, as illustrated in the next figure is 7.3%, and by 2002, the rate of decline had increased to 14%!

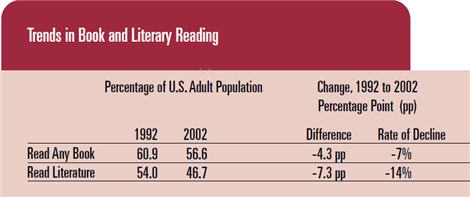

It’s somewhat cold comfort that the rate of decline in the reading of “any book” decreased by half of the percentage of the decline in the reading of literature.

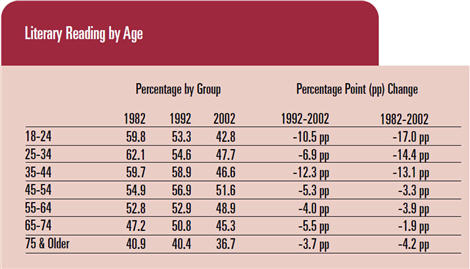

Not many will be surprised, though most of us will remain concerned, that the decline in reading is most pronounced in the young, although the following chart encompasses those up to the age of 44! Even the “elderly” are partaking of the slaughter, but in far more modest numbers.

Looking at similar results from a slightly different statistical perspective, while the U.S. population increased by nearly 40% between 1982 and 2002, the percentage reading literature dropped by just over 10%.

What conclusions to draw from this arguably grim data? I think that the pessimist’s viewpoint is well-represented by these charts (and more so in the original report – recommended reading). But it is worth focusing on the brighter side of the picture. Two data points stand out: while there is a clear shift away from literary reading, the reading of the broad range of books published does not show as steep a decline. Also, the North American population will continue to increase, and this will to some extent ameliorate the trend from the publishers’ perspective – although the nature of what they publish will have to change if they wish to hold their own against the trends so clearly illustrated here.

The other question remains as to what percentage of all books sold annually could be classified as “literary.” I suspect the percentage is modest. (I’m still looking for a data source to illuminate this question.)

A revision to this report has just been issued, which I cover also in my blog. To Read or Not To Read, is credibly described by its publisher (also the NEA) as “the most complete and up-to-date report of the nation’s reading trends and – perhaps most important – their considerable consequences.”

A few key data points:

- Nearly half of all Americans ages 18 to 24 read no books for pleasure.

- The percentage of 18- to 44-year-olds who read a book fell 7 points from 1992 to 2002.

- The percentage of 17-year-olds who read nothing at all for pleasure has doubled over a 20-year period.

- Although nominal spending on books grew from 1985 to 2005, average annual household spending on books dropped 14% when adjusted for inflation.

What makes this report both more important and more unsettling than its predecessor is that it is of course more timely, but also that it moves beyond the single category of “literary reading,” taking a broader view of publishing. And that broader view is a bleaker view.

The report was updated in 2017 (link) offering muted good news: “How Do We Read: Let’s Count the Ways brings good news. Using data from the 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA), the report shows that declines in book-reading may not be as severe as previously reported. Instead, the nation’s readership appears to be shifting from print-only to digital and audio platforms. By including e-readers and audiobooks in the way we track overall book-reading, the 2017 rates are closer to those in 2012 and 2008.”

Future of Book Publishing — Trends & Outlook

While the book publishing industry has begun to come to terms with some of the opportunities afforded by the Internet, I fear that this is thus far a case of too little, too late. Of course it’s not merely missed opportunities on the Internet and the Web. More fundamentally, it appears that competing media are slowly eroding the economic base of publishing. Twenty years ago television and music were distracting for the young. In combination with chat, social networking sites, mobile phones and more, the book has certainly met its match.

References

1. Some Additional Statistics

(a) According to R.R. Bowker, “the bible of the book industry,” “despite the popularity of ebooks, traditional U.S. print title output in 2010 increased 5%. Output of new titles and editions increased from 302,410 in 2009 to a projected 316,480 in 2010.”

(b) Mexican author Gabriel Zaid, in So Many Books: “a new book is published every 30 seconds… it would still take 250,000 years for us to acquaint ourselves with those books already written. Simply reading a list of them (author and title) would take some fifteen years.” According to industry scholar Albert Greco, “If you publish a book today, you’re going to be one of 8,473 for the day.”

(c) As quoted at the beginning of this piece, “Bowker, the world’s leading provider of bibliographic information, released statistics on English-language book publishing compiled from its Global Books In Print database.

“According to Bowker, publishers in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand released 375,000 new titles and editions in 2004. Anglo-American publishers published 80% of all new English-language books in 2004, while the U.S. alone accounted for 52% of the total. Including imported editions available in multiple markets, the total number of new English language books available for sale in the English-speaking world in 2004 was a staggering 450,000…

“The English-speaking countries remain relatively inhospitable to translations into English from other languages. In all, there were only 14,440 new translations in 2004, accounting for a little more than 3% of all books available for sale. The 4,982 translations available for sale in the U.S. was the most in the English-speaking world, but was less than half the 12,197 translations reported by Italy in 2002, and less than 400 more than the 4,602 reported by the Czech Republic in 2003…”

2. The Impact of Bestsellers

The U.S. News & World Report noted that, “for the most part, it seemed a winner-take all victory, with the top 200 bestsellers accounting for about 10 percent of the whole. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince by itself generated 7.02 million sales – 1 percent. Would-be writers are advised to do the math before quitting their day jobs.”

3. Why Publishers Love the Bible

This article by Daniel Radosh, published in The New Yorker, is a fun and fascinating look at the business of bible publishing in the United States. Publishing and selling “Christian” books is a massive business, often overlooked when the book publishing industry is discussed. According to the Christian Booksellers Association, “sales of Christian products by CBA member suppliers through all distribution channels are valued at $4.63 billion.”

Bibles comprised nearly 20% of that number. As reported in the former Google Answers, “No one really knows how many copies of the Bible have been printed, sold, or distributed. The Bible Society’s attempt to calculate the number printed between 1816 and 1975 produced the figure of 2,458,000,000. A more recent survey, for the years up to 1992, put it closer to 6,000,000,000 in more than 2,000 languages and dialects. Whatever the precise figure, the Bible is by far the bestselling book of all time.”

4. What Did Gutenberg Invent?

This fascinating Web-based series of articles challenges the most fundamental claim about Johannes Gutenberg: that he in fact was the European inventor of printing using movable type. Researchers Paul Needham and Blaise Aguera y Arcas have made a new discovery that throws doubt on this long-cherished belief. As the article notes: “Paul and Blaise’s findings suggest that the development of the printing process was more gradual than previously thought…. Their working hypothesis on how Gutenberg created type is that a temporary mould was created, one letter cast and the process of taking the letter out of the mould disturbed the surface. So the same mold would have had to be recreated to make the second letter.” They conclude that the process for creating movable type in Europe was more likely discovered in Italy some 20 years later. (And don’t forget the contributions from China and Korea!)

5. The Writers in the Silos

Heidi Julavits’ superb short piece of creative nonfiction, The Writers in the Silos projects the future of publishing as nothing has before.

6. Poetry

According the August 2007 Harper’s magazine Harper’s Index (subscription required) a book of poetry must sell 50 copies per week to appear on the Poetry Foundation’s bestseller list.

7. All-Time Best-selling Books

Wikipedia offers a fun entry, “List of Best-Selling Books,” providing “lists of best-selling single-volume books and book series to date and in any language [although the focus is mainly English]. ‘Best-selling’ refers to the estimated number of copies sold of each book, rather than the number of books printed or currently owned. Comics and textbooks are not included in this list. Book versions of plays, like Shakespeare’s works, are also excluded. The books are listed according to the highest sales estimate as reported in reliable, independent sources.” There are