May 23rd, 2021

This blog post is a love song to backlist books. Confined to the shadows beneath the bright light of publisher frontlists, these books are too often neglected. But there are many gems on the backlist: books with proven potential and solid profit margins.

Eat your veggies: every publisher knows that focusing attention on the backlist is good for them, and will at least pay lip service to the notion. But translating good intentions into effective action proves to be a barrier for many, perhaps for most — all but the largest publishers.

In the post I want to explore the backlist, how it’s defined, its history, nature and, most importantly, what can be done to make the backlist shine. My focus is on nonfiction backlist titles, for reasons I’ll later describe.

Who is this post for? I’d like to think that anyone working in publishing, or fascinated by publishing, will find something here to enjoy, something to learn. Researching the post I was startled to discover that most discussions of the backlist only scratch the surface, whether in industry trade journals or in the many books that try to tell us how publishing works. I hope this will fill a gap.

It’s a long post, nearly 9,000 words, so you might want to snack on sections, rather than taking on the whole thing in one sitting. I’ve linked at the end of the post to both a PDF and an EPUB version, should those be more convenient.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Backlist

Every publisher has a picture in their mind when they hear the term “backlist,” but it’s revealing to consider how definitions can vary in their specifics.

Albert N. Greco provides about as straightforward a definition as could be imagined: “An old title that continues to sell.” Then in a 2015 book he revised his definition to “an older book (originally released between 9 and 12 months ago) that continues to remain in print.”

There are a range of claims as to how recent a title should be in the move from frontlist to backlist. Six months, twelve, a “season.” A 2006 New York Times article defines frontlist as “titles less than one year old.”

Seth Godin, who has authored two dozen books, offers a pithy perspective: “The backlist is the stuff you sell long after you’ve forgotten all the drama that went into making it.”

Let’s go to “backlist” as a noun, one the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “(A catalogue of) books still available for sale by a publisher or bookseller, but no longer classified by him (sic) as ‘current’ or ‘new’.” Backlist, by default.

The OED attributes the first appearance of the term to the fourth edition of Stanley Unwin’s The Truth about Publishing, published in 1946. In it he wrote “The most stable firms are usually those which have a strong back list (sic) of publications with a continuous and profitable sale and who therefore have no need to gamble to secure new business.”

(Oxford tells us that “backlist” can also be a verb, meaning “To place (a book or other publication or release) on a backlist.”)

Another definition leans to the functional: if a book is being advertised or actively promoted by the publisher, it’s frontlist. If it’s a book that gets reordered when the last copy disappears from the shelf, it’s backlist. (This definition, though revealing, fails to embrace publishers’ increasing interest in backlist promotion.)

My definition leans toward the nebulous: “Backlist is a state of mind.” Publishers know when a title is no longer frontlist. They feel it in their bones the moment when a bestseller like Michelle Obama’s Becoming has transitioned, even though it might still be stacked on the front tables in chain bookstores.

Is there a territory between frontlist and backlist, a kind of limbo some books might visit in the transition from one to the other? “Midlist” isn’t the right term, as it’s used in a different context. I’m thinking about other instances of ‘front’ and ‘back’, perhaps in corporate structures, which often include a front office and a back office. What’s in between the two? The lunch room, of course, a place where you can pause for a few minutes or an hour. So let’s keep in mind that a book can enter a lunchroom phase, continuing to merit some frontlist-style promotional effort, while elegantly heading toward its (hoped-for) backlist home.

Why Backlist Matters

Backlist matters for two simple and connected reasons: it’s two thirds of what people buy, and it’s markedly more profitable for publishers, with better margins and fewer returns from bookstores. Period.

Frontlist vs. Backlist

Isn’t it interesting: you can’t talk about the backlist without talking about the frontlist, but the reverse isn’t true. A backlist book has to come from somewhere, while a frontlist book could, in theory, die and be buried after a year, a season, whatever. (If all of the books with f*ck in the title disappeared tomorrow you would not find me shedding a tear.)

There’s an inherent tension between the frontlist and the backlist — one often robs sales from the other. The tension is increasing. But the frontlist’s challenges are not solely, or even primarily caused by the backlist. A topic for another blog post.

Backlist Sales on the March

As I was researching this post, the New York Times ran a piece looking at COVID’s impact on book sales in 2020, finding a shift toward the backlist. “The pandemic altered how readers discover and buy books, and drove sales for celebrities and bestselling authors while new and lesser known writers struggled,” it said. Seeking an explanation for the shift, the article continued: “Unlike the serendipitous sense of discovery that comes with browsing a bookstore, people tend to search by author or subject matter when they shop online, limiting the titles they see. Often, they see whatever a search or algorithm delivers, or find themselves steered toward titles that retailers push because they are already selling well. As a result, many of the new books that were released in 2020 languished, as panicked retailers focused on brand-name authors and readers gravitated toward the most popular titles… older titles… backlist.”

(Jane Friedman takes issue with several claims in the article. Read her post here.)

Clearly brick-and-mortar booksellers showcase the frontlist more effusively than online resellers. Most bookstores were shut down for part of 2020, impacting the balance of sales. As Sourcebooks’ Dominique Raccah confirmed recently “bookstores are still the primary means for customers to discover frontlist titles.”

Several other recent articles expand on the theme that backlist sales during COVID are up significantly over historic averages.

In terms of percentage of sales, NPD reported (via Publishers Weekly) that for 2020 “backlist titles accounted for 67% of all print units purchased in 2020, up from 63% the year before. In 2010, backlist accounted for only 54% of all unit sales.”

BookNet Canada also noted that backlist sales are higher than usual, accounting for 65% of 2020 sales, up front 60% in 2018.

According to Publishers Lunch (subscription), “Backlist continues to grow even stronger, comprising 70 percent of print sales in the first quarter 2021.

(The trend was even more pronounced in business books where “86% of sales were backlist titles. When you look at the dozen titles that sold over 100,000 copies in the business category last year, none were published in 2020.”)

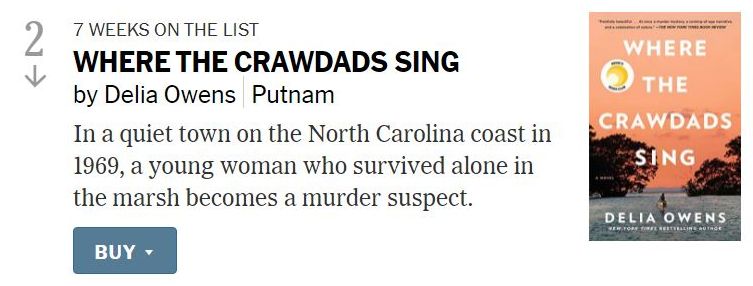

What to make of these reports? Because the data gatherers’ most common definition of the backlist is “titles more than one year old,” exceptionally successful recent titles like Where the Crawdads Sing (1.1 million print copies sold in 2020) and Michelle Obama’s Becoming (600,000 sold in 2020), skew the stats — these books that have more of the characteristics of frontlist titles than archetypical backlist.

Further, when you look at 2020 sales by category, juvenile and young adult fiction and nonfiction all enjoyed double-digit growth (while adult fiction was up 6%, and nonfiction 4.8%). Many of those sales were, by all accounts, affected greatly by COVID’s early stay-at-home orders; 2020 was far from an average year.

Summary: The shifting mix of backlist versus frontlist sales may be overstated. But does that matter? Even if a mere half of a publisher’s sales are backlist titles, that’s plenty of reason to place a continuing focus on the category.

Direct-to-Backlist Publishers

Also worth mentioning is what I call “direct-to-backlist publishers” — publishers who eschew the front tables in bookstores, instead aiming for steady rankings in topics that sell consistently — cookbooks, crafts, sports, pets, that sort of thing. When I google “direct-to-backlist publishers” I find no relevant results. Perhaps it’s considered an insult. I think there’s real craft involved in publishing durable backlist books, and compliment Sterling Publishing, Dorling Kindersley, Fox Chapel, Callisto Media, and others on their focus and commitment to creating beautiful books that can sell over many seasons.

A History of the Backlist

There’s a rich history of well-established titles that, for a multitude of reasons, continue to sell steadily. It goes back a ways: after all, Gutenberg published a German poem before he printed the bible — was this the first European backlist title?

As noted above, the term itself dates to 1946.

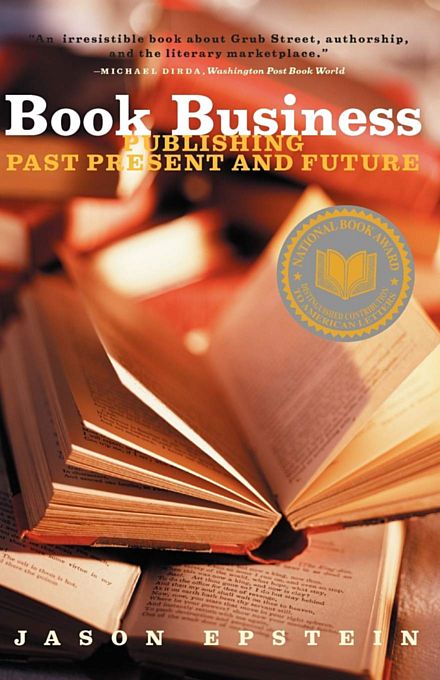

A good source for understanding the history of the backlist, and how things have changed, is Jason Epstein’s Book Business, Publishing, Past, Present and Future.

Epstein writes: “Traditionally, Random House and other publishers cultivated their backlists as their major asset, choosing titles for their permanent value as much as for their immediate appeal, so that even firms grown somnolent with age and neglect tottered along for years on their backlist earnings long after their effective lives were over. But even the strongest publishers depended on their backlists and regarded bestsellers as lucky accidents. It was these books that proclaimed a firm’s financial strength and its cultural standing.”

Epstein references the memoirs of Random House founder Bennett Cerf, who wrote:

The backlist of Random House, Knopf and Pantheon put together is so good that I think if we closed up the whole business for the next twenty years or so, we might make more money than we’re making now, because our backlist is like reaching down and picking up gold from the sidewalk. There’s nothing like it.

(From: At Random: The Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf)

From The New York Times, way back in 1990: “The backlist is the financial backbone of the book industry… It takes years to develop a strong backlist, which is why publishers buy those that become available .”

One of the watershed moments in the history of the backlist was a 1979 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that restricted publishers’ ability to write down the value of unsold books sitting in their warehouses. This led to an explosion in remainder sales and a reduction (before ebooks) in the availability of backlist print books. In that era before print on demand, a reprint was rarely economical below +/- 1,000 copies, and few backlist titles could sell that quantity within a reasonable economic timeframe.

Another part of the history of the backlist involves the decline of the mass market paperback. It’s worth a study of its own. You have to have been in this business awhile to remember the excitement when (in 1979) Bantam Books paid Crown Publishing $3.2 million for the mass market paperback rights to Judith Krantz’s Princess Daisy. Frontlist hardcovers became frontlist paperbacks.

These days the original publisher will almost always retain paperback rights, making the backlist more of an organic whole within a publisher’s list. Trying to coordinate backlist promotion through multiple independent publishers is always a challenge. (The alert reader will note that both Bantam and Crown are now part of Penguin Random House, but that’s another story.)

The Role of Booksellers in the Backlist

Booksellers, independent and chain, play an important role in supplying readers with backlist books, and are justifiably proud of this responsibility. They champion favorite books that may find few champions elsewhere. They are an important source of discovery. But their role has to be viewed within the much wider bookselling ecosystem, in which, at least by percentage of books sold each year, they play a relatively minor part (perhaps 20% with independent and chain combined).

There was a time when chain booksellers spoke proudly of their support of backlist tiles. In a 2006 New York Times article, a Barnes & Noble executive is quoted as saying that the backlist accounted for two-third of sales at the chain. “It’s what the business is built on,” he told the reporter.

But Epstein (in his book), describing the move of bookselling toward more expensive real estate in malls and downtown in large cities, pointed out that “high rent demands high turnover and high turnover requires bestsellers.”

John B. Thompson, writing in Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century (1st edition 2010, 2nd edition 2012) considered the impact of the chain booksellers on the backlist at that time, an impact continuing today:

The rise of the retail chains has set in motion a series of changes that have tended to reduce the value of backlist publishing to houses…. the major retail chains have become increasingly frontlist oriented and the discount stores and supermarkets, which have become increasingly important players in the retail market for books, are strongly oriented towards frontlist bestsellers.

An analyst’s report from 2004 put it this way: “Sales of backlist titles will continue to suffer as long as chains continue to gain market share while insisting on carrying selective new list titles/ bestsellers and aggressively monitoring backlist inventory turn.”

In his recently-published Book Wars (Polity Press, May 2021), Thompson looks at how the subsequent decline in chain bookselling further impacted the fortunes of the backlist: “visibility that (could) be achieved for books has shifted from the physical, front-of-store visibility to visibility in the online space.” It’s easy to lose sight of the full extent of that shift.

In 2006, Barnes & Noble, then the largest bookseller in the US, was operating 723 bookstores across the United States, which included 695 superstores and 98 mall stores operating under the B. Dalton brand; the Borders Group was operating around 1,063 bookstores in the US at that time, including 499 superstores and 564 mall-based Waldenbooks stores. Ten years later, in 2016, Barnes & Noble was still operating 640 stores but it had closed all the B. Dalton stores; Borders had gone bankrupt in 2011 and nearly all of its stores had been liquidated.

The increase in the number of independent bookstores over the last decade is roughly 35% — (though with some 50% more locations). But they still represent less than 5% of books sold, and have failed to replace the display space lost to the chain closures.

Postscript: Will the last big chain renew its support for the backlist? In early April 2021, Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt said in a presentation that the chain was “especially keen to add more backlist, an area he admitted B&N had been neglecting.”

The Backlist, Online Booksellers, and Book Discovery

One of the tropes of recent reporting on publishing and bookselling is that (i) backlist book sales are up (measurably true) and that (ii) the reason they’re up is, at least in part, because of the COVID-occasioned increased shift of book sales online. This is worth exploring.

Online bookselling, so the argument goes, favors the tried and true, books that have proven their worth, the top bestsellers and the most popular of multibook authors.

I look at the “long tail” of ecommerce below, but whatever trend there is toward book sales concentrating in already successful titles is as much a failure of publishers’ marketing efforts (and, to a lesser extent, authors’), as it is the nefarious workings of online search algorithms.

Most product searches begin on Amazon. The same algorithms that drive shoppers to bestsellers drive them to a far wider range of titles as well. A book’s metadata, done right, leads buyers to the books that match the topic of their search, regardless of overall sales rank. When I search for books on “residential carpentry,” I’m presented with Larry Haun’s The Very Efficient Carpenter: Basic Framing for Residential Construction, not with the latest Harlan Coben thriller. And I’m offered a half-dozen alternatives on the topic.

What is certain is that when a consumer searches for a backlist book they are probably not going to find it in their local bookstore. They are almost certainly going to find it, new or used, on Amazon, and can receive it, in some cases, the same day. This is the simple reason that Amazon (and the online used-book resellers) account for more backlist sales than do bookstores.

X% of Sales: How Big is the Backlist?

There’s a wide disparity among publishers in the percentage of their sales generated by the backlist. And there have been multiple shifts in these ratios over the past several decades.

Leonard Shatzkin (industry analyst Mike Shatzkin’s father) talks extensively about the backlist in his 1982 book In Cold Type: Overcoming the Book Crisis. Though much of what he discusses is particular to book retail as it existed four decades ago, he reminds us that the issue is far from new.

At that time, according to Shatzkin:

New titles represent approximately 60 percent of publishers’ sales… when I came into publishing in 1945, the ratio was probably the reverse. The backlist represented 60 percent of total sales; today it is down to 40 percent. In thirty-five years, the paperback and the publishers’ pursuit of the big advance have shortened the life of most books dramatically.

Greco, Rodríguez and Wharton, in their 2006 book Culture and Commerce of Publishing in the 21st Century estimate that backlist sales for trade publishers account for “80 percent of a firm’s profit” and for “50 percent of annual revenues” at university presses.

John B. Thompson, in his Merchants of Culture, wrote:

Some trade houses like Hyperion, the publisher owned by the Disney corporation [sold to Hachette in 2013], are overwhelmingly frontlist driven; they have relatively small backlists, amounting to no more than 20 per cent of their sales, and they are hugely dependent on their ability to publish a number of frontlist bestsellers every year in order to meet their sales targets…

But trade publishers vary enormously in the extent to which their revenues break down by frontlist and backlist… for the large corporations, somewhere between 60 and 75 per cent of the revenue generated each year must come from new books.

As we saw above in the most recent data, that ratio has again been reversed.

The Long Tail, Ecommerce and the Backlist

Chris Anderson first described his much-referenced Long Tail theory in Wired magazine back in 2004. Its premise for publishers is that the Internet makes it easy to distribute and sell just a few copies of a book (the initial costs of publication having usually been recovered).

And between ebooks and print on demand, keeping the long-tail titles available for sale is a cinch.

The question ultimately is whether or not the spot you occupy on the long tail brings enough buyers to your book to make even a small administrative effort worthwhile.

In his subsequent book exploring tails, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, Anderson writes:

In 2004, 950,000 books out of the 1.2 million tracked by Nielsen BookScan [new and backlist] sold fewer than 99 copies. Another 200,000 sold fewer than 1,000 copies. Only 25,000 sold more than 5,000 copies. The average book in America sells about 500 copies. In other words, about 98 percent of books are noncommercial, whether they were intended that way or not.

What does this say about the backlist? Let’s assume that the 2004 data is more or less true today. You don’t want your backlist title to be one where sales have dropped below 99 copies/year (8 copies/month) — there’s not much that can be done to bring it back to life. What if, magically, you could double the sales this year: another 100 copies? Would that be worth the effort?

The 200,000 titles with sales between 100-999 still have a beating heart. Let’s try a simple scenario: Sales of 500 copies/year; net revenue of $15/copy; profit contribution $3.00/copy. If you can believe that you can boost those sales by just 10% you’ve got a $150/title budget to work with, and might succeed in pushing sales even further. Below we’ll take a look at what that money can buy.

Anita Elberse’s Blockbusters thesis could be described in part as the anti-long-tail argument. Elberse is adamant that in the “fiercely competitive world of entertainment: building a business around blockbuster products… that are hugely expensive to produce and market―is the surest path to long-term success.”

Analyzing Anderson’s long tail hypothesis in the Harvard Business Review, Elberse writes “First, the tail is long but extremely flat—and, as online retailers expand their assortments, increasingly so. Second, compared with heavy users, light users have a disproportionately strong preference for the more popular offerings, while both groups appreciate hit products more than they like those in the tail.”

In her book Blockbusters: Hit-Making, Risk-Taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment, Alberse outlines a depressing example from the music industry. Of the 8 million unique digital tracks sold in 2011… 94%—7.5 million tracks—sold fewer than one hundred units, and “an astonishing” 32% sold only one copy. “Yes, that’s right,” she assures us. “Of all the tracks that sold at least one copy, about a third sold exactly one copy.”

It’s a challenge to reconcile the two theses. For the larger publishers, who can invest in bestsellers, Elberse provides a powerful argument to maintain their blockbuster-first strategy. But she is not suggesting that publishers ignore the backlist, only that they temper their expectations. As I see it, Elberse is also reinforcing the power of backlist promotion. Still, the best way to create a durable backlist is to build a strong frontlist. Few backlist titles are undiscovered diamonds in the rough.

The Midlist

From Publishers Weekly: “The midlist is like the middle class; it’s the group that gets squeezed. They don’t get the support from their publishers. They don’t get their due [as writers]. They don’t get the attention they deserve from reviewers.”

Midlist is a deceptive term, not really a part of the same terminology as frontlist and backlist. As I mentioned above, logically it would mean books that aren’t on bestseller lists, but are not yet languishing in stores with single copies, spine out. The term “midlist” would represent a temporal phase.

But a title is born to the midlist, it doesn’t transition there. It’s the middle child, not the smart & beautiful first born, nor the runt of the litter. It is born of modest expectations, not expected to be a bestseller, but deemed unlikely to be a major disappointment. In terms of sales volume (or rather anticipated sales volume), a midlist book resides between the frontlist bestsellers and the backlist. (Greco, Rodríguez and Wharton, in their 2006 book Culture and Commerce of Publishing in the 21st Century: “Midlist books generate total sales in the range of 5,000 copies; tallies beyond 7,500 copies are a cause for jubilation.” That still sounds like a reasonable number.)

But each new midlist book is also frontlist (for about a year), and a midlist book will usually become also a backlist title (once it’s been around awhile). And so the term remains ambiguous, and, for this discussion, a little misleading.

Publishers Tend to Disdain the Backlist

A publisher’s failure to fully embrace its backlist could be mere benign neglect. But is it sometimes something more?

Publishers tend to be judged by the editorial and sales success of their frontlist, rather than the financial performance of their solid, stolid backlist.

The frontlist is like a drug. Frontlist is sexy, or just plain fun — acquiring new titles and trying to turn them into bestsellers. When people dream of publishing careers they dream of discovering new authors and transforming them into bestselling Nobel Prize winners — they don’t think about goosing the sales of an old book on carpentry or knitting.

Seth Godin again: “It’s more exciting, more fun and more hopeful to seek out and launch new books. It’s the culture of many industries, particularly ones that are seen as creative.”

Laura J. Miller, in her Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption writes that “(for booksellers) the frontlist… tends to generate an excitement that comes from the prospect of new discoveries.”

Mike Shatzkin, writing about backlist a decade ago:

Most publishers “learn” (institutionally) that it isn’t worth promoting backlist. To begin with, most publishers aren’t staffed to do it: the head counts and working processes of publicity and marketing departments are built around the requirements of “launching” books, not “piloting” them.

John B. Thompson, Book Wars: “The fiscal demands and incentives of publishing organizations favor short-termism.”

In the frontlist negotiation (it’s) far more interesting for (publisher sales reps and booksellers) to talk about the future, with the tantalizing promise of “big” books that may catch the public’s fancy and sell in large quantity, than to deal with familiar, routine backlist titles that have lost their mystery and excitement.

Used Books and the Backlist

A fly in the ointment of backlist marketing and promotion is watching the effort get partially siphoned off into the used book market. It’s difficult to pin down the extent of the issue — U.S. Census Bureau data doesn’t record used book sales within book retail overall. But it’s substantial.

Back in 2006 the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) published a comprehensive survey of the used book market based on 2004 sales data. The market is large: $2.2 billion at that date, 8.4 percent of total consumer spending on books. But textbooks comprised three-quarter of the sales volume (though only a third of unit sales — textbooks being more expensive), leaving trade used books sales at $589 million. Some percentage of those were for titles out of print, and so not cannibalizing new book sales.

The BISG study found that used book sales in used-book stores and new-book stores (separate from online sales) totaled $1.57 billion in 2004. U.S. Census Bureau data for all brick-and-mortar book sales in 2004 is $2.2 billion. That would put used book sales at just over 70% of brick-and-mortar book sales.

Without updated stats, it’s tough to pin a number on used book sales in 2020-21. The online used book sellers have a broader reach today, and are far more aggressive, expert at setting irresistible retail prices for their inventory, sometimes as low as a penny (plus $3.99 shipping, which is where they make their margin on those transactions). (The New York Times profiled this marketplace in 2015.)

In the end, used book sales are, for publishers, a “cost of doing business.” They were fortunate that it was made illegal to sell used ebooks, but the second hand book market has been litigated and continues apace.

What Makes a Book a ‘Good’ Backlist Book?

At some point nearly all new books cross the river into that rough territory called backlist. Some live there for years, even for decades. It’s worth positing the question, “What makes a good backlist book?” Alongside that question another could be posed: Can you acquire a frontlist title with a goal, at least in part, that it will also thrive as backlist?

Put yourself for just a moment into the shoes of an editor and ask: What would turn a nonfiction manuscript into not just a success out of the gate, but also a great backlist book, of ongoing interest to readers, even if the information therein is no longer, per se, fresh? There comes a time in the life of every nonfiction manuscript where the editor in charge should ask the question: how can I plan to maximize the life of this book, as a backlist title, without clouding the many characteristics that make it so compelling and fresh today?

What makes a strong backlist book? It’s easy to say that a great backlist title is one that sells a whole lot of copies, over many years. But can’t we characterize these titles beyond their sales rank? If judged just on sales, To Kill a Mockingbird would be a great backlist fiction title. Published in 1960, the paperback is still in the top 100 bestsellers on Amazon. According to Keel Hunt in his The Family Business: How Ingram Transformed the World of Books, “HarperCollins actually earns far more of its corporate profits from… To Kill a Mockingbird, which sells an estimated 750,000 to one million copies annually.” (The New York Times says it’s over a million copies each year.)

But you can hardly approach an author with the suggestion that they write a novel to dislodge Mockingbird from its loft, or ask an editor to assign that task to any of their fiction authors.

I can imagine a scenario where you’d have to choose between two manuscripts on offer for similar advances, where you might judge one would sell more in the short term, but the other more likely to enjoy backlist success, and greater sales overall. The choice would not be easy.

Let’s journey into the territory of an average backlist title.

I wonder why Amazon’s #1 bestseller in carpentry is Larry Haun’s The Very Efficient Carpenter: Basic Framing for Residential Construction? Published in 1998, its 224 pages, with black & white photos, retails in paperback for $25.95. Haun, who died in 2011, has three other books in print, none selling nearly as well. What is the secret that keeps it one step ahead of the #2 carpentry title, Will Beemer’s Learn to Timber Frame: Craftsmanship, Simplicity, Timeless Beauty? It’s not the suggested retail price — they’re a dollar apart.

It’s obvious, but worth noting, that the greater the success of a title while new, the greater the chances for a happy life on the backlist — with strong worth of mouth, many readers will spread the word to new audiences.

Todd Sattersten wrote a fascinating blog post evaluating what frontlist sales success can tell us about the backlist prospects for a title. The data in the post is detailed and I won’t repeat it all here. His thesis surrounds “the magic number,” i.e. a point where momentum takes over from market resistance and a book starts to “sell itself.” That number, he determines, is first year sales of 10,000 copies. If a book sells fewer than that, it has an insignificant chance of selling 100,000 copies over its lifetime. However, “if you can break 25,000 copies, there is a 47% that you can get past 50,000 copies… in lifetime sales.”

Here are a few factors that I think could be indicators of backlist promise. I’m just scratching the surface, hoping to energize some ideas of your own:

- Focused on more than just a current event.

- Not specific to just one country, or at least combining an international perspective.

- “Educational,” in the “could be assigned as supplemental reading” sense.

- Includes the “How” as well as the “Why”.

- Well-suited to rich illustration, including photos and graphics.

A Brief Diversion: The Backlist Wars

John B. Thompson’s Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing, is certain to become this year’s must-read for anyone serious about the publishing industry.

Chapter three is called “The Backlist Wars,” and describes the genesis of Arthur Klebanoff’s RosettaBooks (launched 2001) and Jane Friedman’s Open Road Integrated Media (founded 2008). Along the way Thompson provides a thorough investigation of the significance of the backlist to the trade book publishing industry. Consider this: Friedman was able to attract venture capital to Open Road, as much as $19 million, more than ten times the median money received by other funded publishing startups.

The two companies enjoyed considerable early success, hampered by ongoing litigation from the established Big 6 (at the time) publishers. Sales reached $4 million/year at RosettaBooks and $15 million at Open Road.*

(* In early May 2021, Klebanoff announced the sale of his 700-title backlist catalog to a media investment firm, MEP Capital, who have previously backed “world-class producers, rights holders, artists, and creative entrepreneurs.”)

Both ran up against the limits of growth — there were only so many valuable backlist titles that could be licensed directly from their authors, bypassing the original print publisher.

Thompson concludes that the business model is at best, niche. More significantly he notes that “a vibrant publishing ecology needs the constant creation of the new as well as the repackaging of the old. It needs publishers who are willing to take risks with the new, and who have to be able to offset the risks involved in publishing the new by relying on backlist sales to make up a substantial part of their revenue.”

The Half-Life of Backlist Books

“But the big problem for the publishers is that backlist inexorably “decays” in sales power year by year. Titles, particularly nonfiction, become dated… …a backlist beating last year’s sales is only an occasional event.

— Mike Shatzkin

At what point does the new and fascinating become old though still interesting? At what later point does that backlist title cease to be relevant and cease to be saleable? It’s an important part of backlist management: in a changing world a certain degree of atrophying is almost certain.

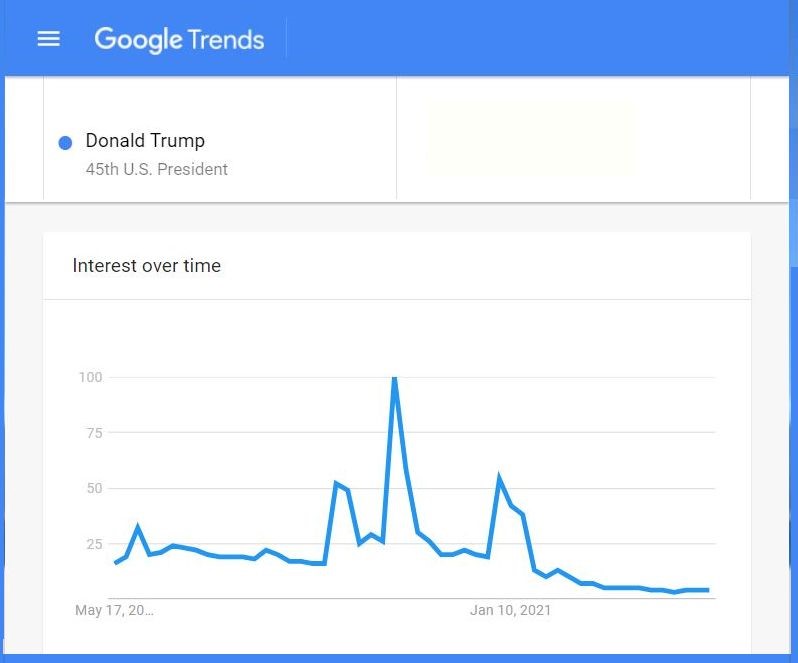

“Topicality” is a force that can’t be sidestepped. A perfect example of the double-edged sword of topicality is books about Donald Trump. They had a great run. But look at the chart below — I don’t think you’ll be surprised. As a topic for bestsellerdom, Donald Trump has dropped precipitously. On this week’s New York Times bestseller lists he is nowhere to be found.

But, of the many books written about the former president, what could have been added or enhanced that might have extended those books’ lives? More historical background? More detail on some of the secondary characters? A better index? A section of color photographs? You get the idea. These would be investments not just for the short term, but for the longer one — a publisher committed to the backlist would support such investments.

What does an average backlist sales atrophy look like? Is it a 10%/year drop? 20%? 50%? Of course there’s so much inherent variability from one title to the next that I doubt we could find a statistically-valid formula against which to judge multiple titles. Topicality is a major factor for political books, but has little impact on books about residential carpentry. Self-help books are certainly subject to fads and fading interest, though some endure.

If the sales of a five-year-old backlist title dip 33% in year five, after an elegant 5% per year decline for the preceding four years, is that a meaningful signal?

I think the only rigorous framework for evaluating a backlist title is to ask: if this book showed up today as a book proposal, would we welcome it? Would we publish it?

Everything Old is New Again: Refreshing the Backlist

(Sales executive) Charlie Nurnberg… often reminded me that “every book is new to the person who hasn’t heard of it yet.” —Mike Shatzkin

“On the Internet, especially when you are an ebook, no one knows you are a spine-out title in a regular bookshop… In fact, if you have a nice cover, a good blurb, a sensible amount of metadata and a good price, you will be accepted along with the freshly published, the self-published and the badly published, just one more option in a vast sea of options.” —“No One Knows You’re a Backlist Book,” Eoin Purcell

I think there’s an “existential” concept that a publisher needs to embrace before embarking on backlist renovation: Not a book in the world that has yet reached all its potential readers. But how many readers remain? And how many new readers will emerge from this year’s college graduating class, or from the many ESL programs? If a particular backlist book was being published as a brand new title tomorrow, how would you expect it to fare in the marketplace?

It’s easy to imagine that some multi-year bestselling titles like Where the Crawdads Sing may have reached 90% of their potential market. But Crawdads, first published in fall 2018, continued to be the top fiction bestseller in 2020, and is now #2 on the New York Times trade paperback fiction bestseller list in mid-May, 2021. And with a movie in the works it will certainly find many more new readers. (November 2025: Still going strong: #13,381 in Kindle store.)

Deciding to renovate a backlist title calls for a cost/benefit analysis. While the cost of any specific tactic can be accurately budgeted, the benefit, pro forma, can only be estimated.

What’s the simplest way to promote a backlist title? Drop the list price by 20%. The problem, of course, is that sales will have to increase by about 25% just to break even on the maneuver. One good thing about online selling is that it’s easy to test simple propositions like price adjustments. If it’s not working out in a few months, revert to the original price, or something in between.

Let’s go beyond price and consider other opportunities, some easy to implement, others not so easy.

Requires changing some part of the book, text or appearance

- New foreword/preface/intro

- A fully revised edition

- New cover

- Revamp the author’s other published titles to provide a visual continuity

- Add an additional format — perhaps a mass market paperback or print on demand hardcover

- Make the EPUB file fully accessible

What you can do without touching the book itself

- Price drop/price promotion

- Metadata enhancement

- International sales promotion

- Social media marketing

- Online advertising: Amazon, Facebook, Google, etc.

The Backlist Success Rate

Following on Todd Sattersten’s magic number thesis, I’d like to propose a measure I’m calling the BLS, the Backlist Success Rate. My thinking is, at best, preliminary. But here’s the idea:

Publishers “A” and “B”, both founded in 2010, both publish 10-12 new books per year, and so by 2021 have a backlist of roughly 100 titles each. Half of Publisher A’s backlist titles still sell at least 500 copies/year, while only a quarter of Publisher B’s backlist enjoys that much activity.

Using my simple formula…

… Publisher A would have a BLS of 5.0, and Publisher B a score of 2.5.

You’ll immediately spot the major hole in my thesis, and of course in the accompanying formula. The point is that backlist evaluations can be both quantitative and qualitative. Not everything in publishing is a unique case.

Print on Demand and the Backlist

Print on demand (POD) is 25-year-old technology, though still underappreciated and underutilized by many book publishers. For some time, the problem with POD was quality — just not quite good enough, not as good as offset printing; buyers could detect the difference. These days it’s plenty good enough for black & white books, even does a good job with the photographs. With four-color books it can fall short, though not by much. Most readers don’t notice.

POD is really two different products when supporting the backlist. People often think of it as printing just a single copy of a book to fill a special order. Though the margin is lower on POD books, that becomes secondary if a sale would otherwise be lost.

But POD is also a short-run offering, serving a market where offset printing isn’t economical, or, often, for instances where offset takes too long to meet a bump in short-term demand. (Ingram calls this “just-in-case” printing.)

(There’s another sub-sector of the short-run market, mostly serving independent/self-published authors and many academic presses with obscure titles, where a first printing of fifty or a couple of hundred copies is a prudent initial foray into the marketplace for a frontlist book.)

Today most offset book printers include POD services. Quality and pricing is similar. A variety of considerations go into choosing a short-run service, which are beyond the scope of this post. But one company stands apart from all of the others, not because they’re great printers, but because of their enormous distribution network and state-of-the-art logistics. That, of course, is Ingram, which operates POD and book distribution services for publishers large and small, via Lightning Source and IngramSpark.

In his Ingram history, The Family Business, Keel Hunt writes “Lightning Source was beautifully designed to help publishers take advantage of the long-tail phenomenon… Suddenly, it (was) feasible for a publisher to realize the aggregate sales potential of those thousands of “little” books… By 2020, Ingram’s fiftieth year, the Lightning Source digital library included more than eighteen million titles.”

Mike Shatzkin, quoted in the same book, postulates that for publishers “setting up every new title at Lightning Source might become a standard routine, no matter how big or small the first printing is.”

I don’t want to make this post an advertisement for Ingram, but the value they offer is considerable.

Special Sales of Backlist Books

If print on demand is underappreciated and underutilized by many book publishers, “special sales” is even more so, another case of something easier to explain than to implement.

The use case is straightforward. For example, take your #1 backlist book on residential carpentry. Your special sales rep would convince Home Depot to put a dozen copies in each of their 2,200 North American stores, next to the nails section, and sell another 500 copies to the leading provider of online training for home carpenters, which they would use as a promotional gift for new registrants. Easy, no?

Brian Jud is the industry leader in promoting and educating publishers on special sales. He founded the Association of Authors and Publishers for Special Sales (APSS), “advancing the success of publishers in non-bookstore marketing.” I suggested to Brian that special sales are 90% backlist books and 90% nonfiction, and he responded that those numbers are “in the ballpark.”

Every special sale is a Las Vegas jackpot — found money, as it were.

But I get it: there are just so many things you can do in a day, between promoting the frontlist, then the midlist, then the backlist. Where are you going to find the time to make cold calls on hardware stores, hoping to convince them that your book should be featured, when they currently don’t carry books at all?

This too is a subject for a much longer post, but I wanted to make sure to put it on the list of promotional opportunities for publishers for the backlist.

Metadata, and Marketing the Backlist

Backlist marketing has one essential characteristic that differs from frontlist marketing. It’s the difference between promoting individual titles, one at a time, and promoting a mass of titles with a unified strategy and set of tactics.

Frontlist promotion is mostly art; backlist promotion is mostly science. Frontlist marketing is intimately tailored to each title, each author and each market. Backlist promotion seeks to find a set of common elements that work across a group of titles. Invariably that involves metadata enhancement.

There are a half-dozen published studies describing the impact of improved metadata on book sales. You’ve probably seen one or more. The most recent is Nielsen UK’s 2020 study (can’t find a download source). With each new study the research methodology becomes more precise and the findings more credible. Just some topline numbers: including all five core descriptive metadata elements (keywords, short description, long description, author biography and reviews) —saw sales three times higher than titles with no descriptive data elements. Titles with just keywords included found their sales increase by more than double.

But sales don’t have to double for the effort to be worthwhile.

Revisiting the metadata of each title — how much time does that take, what does it cost? Best practices for metadata are still relatively young and most publishers have not fully embraced them. This shows up particularly in their backlists, where the metadata was formulated before publishers really understood the concept.

The result is that the average backlist title has one or more of the following metadata issues:

- Poor BISAC code selection, and frequently only one or two codes chosen, rather than the three that most resellers accept.

- Too few keywords (plus inappropriate and repeated terms).

- No author page/author bio.

- Weak book descriptions.

- No post-publication reviews included with the online listing (only prepublication blurbs, which suffer credibility issues).

Those are but five of more than two dozen categories that can be monitored and enhanced (I’ve identified thirty-three in total on the worksheet I use with clients). An excellent resource for developing a strategic approach to metadata can be found in Ingram’s Metadata Essentials.

There are certainly costs associated with metadata renewal. It takes a trained technician, and someone with a flair for copywriting — those are not complementary skills. And it takes some amount of time, perhaps thirty minutes per title, perhaps an hour or more. But you don’t have to sell many more copies to get an ROI on the effort.

Above I described a scenario where a publisher’s backlist included titles with sales of just 99 copies/year. I said that there wasn’t much that could be done to bring those books back to life. I lied.

I believe that if you revisit just the core metadata elements for those titles, you can juice sales by 25%. Using my broad strokes profit contribution calculation of $3/copy, it would add $75 to the bottom line. I bet you could find someone to take on the project for less than $75 per book. And I believe that the sales increase would exceed 25%. What are you waiting for?

While backlist marketing, at its core, works across multiple titles, regardless of the title specifics, there are certainly times when a backlist book has an opportunity to be treated as if near-new.

The obvious recent example is COVID’s sudden impact on books about many health-related topics, which took off last spring.

Publishers need a way to monitor timely opportunities for individual backlist titles.

Ingram acquired, then further developed, a system now called Marketing Insights. Firebrand has its Eloquence on Alert platform. Both provide real-time management of backlist books. Ingram describes Marketing Insight’s features as including the ability to “identify the hidden gems in your backlist” and to “easily spot your titles’ daily correlations, trends, and performance.” Firebrand offers to alert you “when your product data changes on major online retailers, so you can react quickly to protect your investment in your catalog.”

These are powerful tools. For publishers that have yet to invigorate their backlist marketing program they may be even too powerful. Data needs to be actionable to be useful — with a capacity to take action based on the data. The power of these systems relies on a publisher’s commitment to utilizing their demonstrable strengths.

Backlist Fiction

When I write about enhancing backlist I’m mostly thinking about “enhancing the nonfiction backlist,” because I believe that, generally, nonfiction backlist is far easier to boost than fiction.

It’s not that fiction is devoid of relevant metadata or other promotional opportunities. But it just doesn’t afford the same degree of metadata granularity across a range of titles.

While there are 5039 entries on the fall 2020 BISAC subject list, less than 1,000 categories are for fiction (including adult, young adult and juvenile fiction). Surveys show that people might buy a nonfiction book because of the information contained in just one chapter, or even a section of a chapter, where with novels you’re buying the whole lot, the entire work. The result is that BISAC classification is a more powerful tool for nonfiction: the categories are more detailed and specific. Keywords, too, have the potential to be precisely targeted.

One opportunity for promoting fiction backlists crops up when authors pen new titles. More so than with nonfiction, fiction readers form close allegiances to their favorite authors, particularly genre authors. In most surveys asking why someone bought a particular fiction title, “enjoyed other books by the author” gets mentioned between a quarter and a third of the time. So each new book by an established fiction author sparks a backlist promotional opportunity that shouldn’t be overlooked.*

(* “Read others by author/in series” has triple the impact on discovery for adult fiction as for nonfiction. “Like the author” influences a third of fiction purchases, but just a fifth of nonfiction buys.)

Self-published/indie authors often lead the way in their understanding and experience in promoting fiction titles. As just one example, a post by Laurelin Paige, Reviving Backlist Books You Thought Were Dead, outlines ten strategies for fiction, including price adjustments and bundling books with other authors. I admire a fresh approach.

Author Contracts and the Backlist

An emerging trend in author/publisher relations provides another impetus for publishers to up the stakes on their long-tail backlist. The conundrum can be simply described. Publisher contracts have, for many years, allowed the copyright to remain with the publisher as long as the book remained in print. When offset press runs started around 1,000 copies, keeping a book in print represented a real commitment by a publisher. If the book stopped selling, it made economic sense to remainder the inventory, and genially allow the rights to revert to the author

The combined impact of ebooks and print on demand upended the equation. The ebook version is immortal, while printing a single copy at a time became commonplace. The book could be deemed to be still in print.

But this is obviously unfair to the author. If a publisher is not having at least some continuing success with a title, they have no moral right to withhold the copyright from the author. Or is there something I’m missing?

The Authors Guild, in their model trade book contract, make suggestions for addressing this fraught conflict. They note: “Ideally, if a work is only available via print-on-demand or ebook technologies, the work would only be deemed in print if the author receives a minimum floor in royalties over the course of two consecutive six-month royalty periods (such as $250–$500).”

Things are certain to change. But how quickly? It will be one thing for authors, moving forward, to insist on minimum royalty provisions. Adjusting contracts retroactively seems unlikely to become common. There is little incentive for the publishers.

Still, all other things being equal, an ethical publisher will find a way to revert copyright when appropriate.

What’s the best way to avoid conflict? A careful evaluation of each backlist title. If the publisher thinks there’s still potential in the book, then they can put some metadata muscle behind it. The author will be reassured.

Subsidiary Rights for Backlist Books

Yet another way to “refresh” the backlist is to revisit subsidiary rights for each backlist title. You probably haven’t thought much about these rights since shortly after the title was published. Things change, and new opportunities arise, whether for foreign translation or for film and television adaptations (mostly for fiction and some narrative nonfiction). A recent post on Rotten Tomatoes described “125 books becoming TV series we cannot wait to see.” It’s fascinating to see the wide range of genres that the industry is clamoring for.

I included “international sales promotion” on the “refresh” list above. In the absence of rights sales in specific markets, online marketplaces have vastly improved the opportunity to sell English-language books in non-English territories. There are a series of steps required to optimize these opportunities, beyond the scope of this post, but Amazon, Apple and Kobo, in particular, have reinvented the landscape for international book sales.

Some Closing Thoughts

Enhancing the backlist can be simply a mechanical exercise, a few adjustments to the metadata. As such it’s more suited to the left-brained staff in a publishing company.

Seen as a technical challenge, as inertia to be overcome, backlist enhancement can be a game, where different tactics are experimented with, measured and then improved upon. The ease of fine-tuning online listings makes it relatively simple. Set a budget, define a process, determine a test group of titles, and proceed.

There are also numerous opportunities for the right-brained cadre at a publishing company to get their hands dirty seeking creative ways to reenergize specific backlist books.

Publishers have an obligation to their backlist. The verb “publish,” from Latin publicare, does not mean to write a book, to edit a book, to design a book, or to print a book. It means to “to make public or generally known.” The act of publishing is the act of informing the reading public that the book exists. That obligation doesn’t cease when a title is no longer new.

- Photo of stacked books by Jan Mellström on Unsplash.

- Photo of used books store by Darwin Vegher on Unsplash, edited and cropped.