April 2nd, 2019

Updated March, 2024.

In this third post of a three-part series (part 1 is here) (part 2 is here), I’ll focus directly on the book publishing industry and how the next recession could be felt. I hope that an analysis of the impact of past recessions might arm us for the next.

Two posts ago, I looked at various indicators and assessments of when the next recession is coming. Not if, when. Sentiment was growing grim as 2018 came to a close, but stock markets have since rebounded, the job market remains strong, economic growth continues, and neither Brexit nor China has occasioned economic Armageddon. Good.

In the last post I looked at several other publishing and entertainment industry sectors — movies, videogames and music — to see what evidence there is of a recession’s impact on their economic performance. The consensus is that these sectors are between recession-resistant and recession-proof.

I’m not going to look at network and radio broadcast media, and newspapers and magazines, each major topics of their own. Because their business models are heavily dependent on advertising, recessions have quantified repercussions, not so much because the public stops buying (or watching or listening) but because advertisers reduce expenditures. It’s a different kind of challenge.

The interesting outliers in “broadcast” are subscription services for video and music: Netflix, Spotify and their competitors. They are mostly too young for recession performance comparisons. There are a few articles looking at Netflix’s track record in the last recession. One article suggests that “in 2011, Netflix almost melted down. It lost 800,000 customers almost overnight, and the company’s stock price cratered by 80%.” But this was at a disruptive time when Netflix was still pivoting from DVDs to streaming. Two recent posts (here and here) make the argument that Netflix’s loyal user base and dominant market position will largely shield it in a downturn.

Spotify didn’t launch until October 2008, too recent for a reference point, although in this article an analyst suggests that “if there were a downturn right now, Spotify would not be particularly well positioned to weather the storm,” as the company is not yet consistently profitable. (It had its first operating profit in Q4 2018, but still expects to lose 200-360 million euros this year.) (2024: The company still struggles with profitability, but this is not directly related to economic trends.)

Dates of Recessions Discussed Here

- July 1981–November 1982

- July 1990–March 1991

- (March 2001–November 2001 — No publishing sales data found for this brief recession)

- December 2007–June 2009

Of the four, what stands out is the 2007-2009 “Great Recession.” GDP fell 4.3% in the U.S., the largest decline in the postwar era. The unemployment rate peaked at 10% in October 2009 (it stands at 3.6% as of February, 2020).

Book Publishing

Defining economic trends for the book publishing industry is a perilous pursuit. The industry we call “book publishing” is really a collection of several industries — in simplest terms, trade, educational and scholarly publishing. The dynamics of each differs widely, impacted by varied demographic, economic, technological and cultural trends.

A review of higher education publishing illuminates the conundrum. After decades of growth, sales have hit a wall. Porter Anderson, writing in Publishing Perspectives, examined the Association of American Publishers (AAP) data for 2017. It revealed a 24% drop in higher education sales between 2013 and 2018. But in that period trade book sales increased roughly 5% (also based on AAP data), which paints a different picture of the health of the “book publishing industry.”

But the intersection of the broad audience of book readers and the greatest number of titles published is in the trade sector. When someone raises a flag on the decline of writing and reading, they are usually referencing trade publishing.

Where’s the Data?

In the years I’ve been collecting sales data on the book publishing industry I’ve found only two consistently authoritative contemporary sources. The first is an academic, Albert N. Greco, who has been studying and documenting the economics of the U.S. book publishing industry for decades. He is the author or co-author of a half-dozen books on the industry and of many scholarly articles.

The second source is Michael Cader, editor and publisher of Publishers Lunch, a paid subscription service. His focus is primarily trade publishing. Cader susses out the inside story on the publicly-available data and consistently presents a more precise picture of its meaning, than do other sources. His series of articles, Blending Statistics to See the Whole Market (firewall), begun in June 2017, is a superb dissection of the challenges in measuring trade sales data. As he notes in Part 1, “all of the core publishing statistics are incomplete in various ways.”

A well-documented example of poorly-documented data is ebook sales from self-published writers, which Cader pegs at 16.5% of total ebook sales at retail, nearly $500 million in 2016. Units sales clock in at 40% of the market because of the much lower retail prices of self-published books. In Part 3 Cader weaves a detailed estimate of the total trade book market (net income to publishers), some $10.6 billion in 2016.

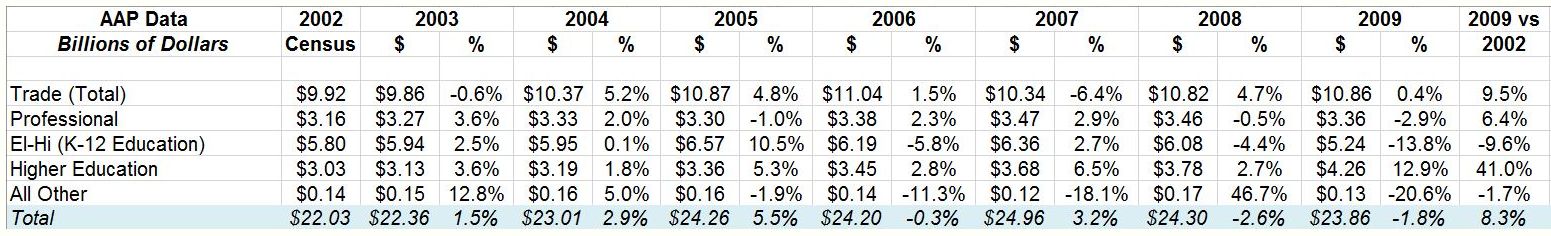

That being said, the best way I’ve found to deal with suspect book sales data is to pull continually from the same data source, apples to apples (or as close as it gets). In 2009 AAP published a chart with sales data from 2002-2009. It’s hard to read, but here goes:

It shows steady growth through 2006, followed by three years of

(cumulative) decline across all sectors (except higher education, still growing strongly).

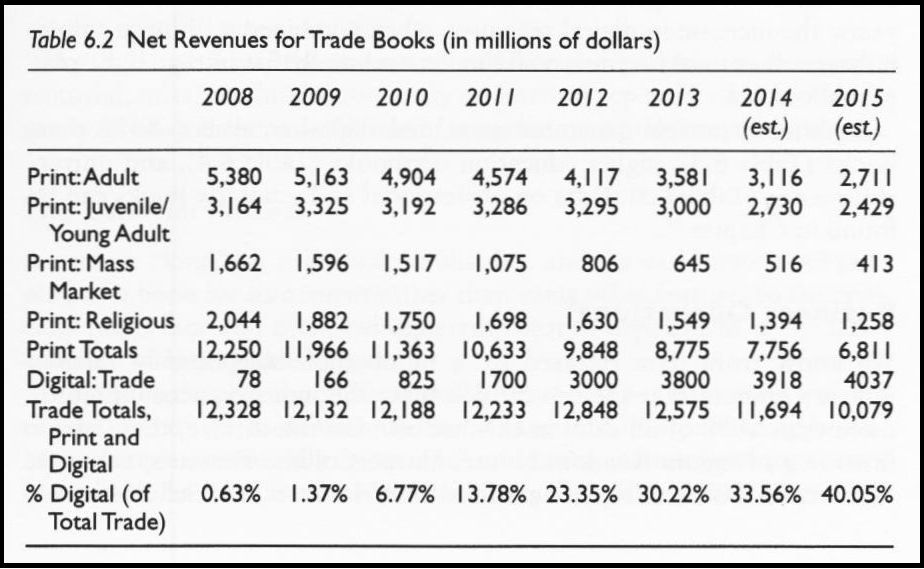

For comparison with the broader economy, GDP fell 4.3%. Figure 2 appears in a book* co-authored by Albert N. Greco.

It shows total trade sales declining slightly in 2009-2010, before resuming an uptick in 2011.

Greco, in another co-authored book** tracks also average hardcover book prices through the last recession, which show a 26% drop between 2007 and 2010, presumably proxy data for an economic decline. Bookstore sales also dropped during this period, but that was in the midst of the continuing shift to online sales and lower-priced ebooks, and then the bankruptcy of Borders in 2011.

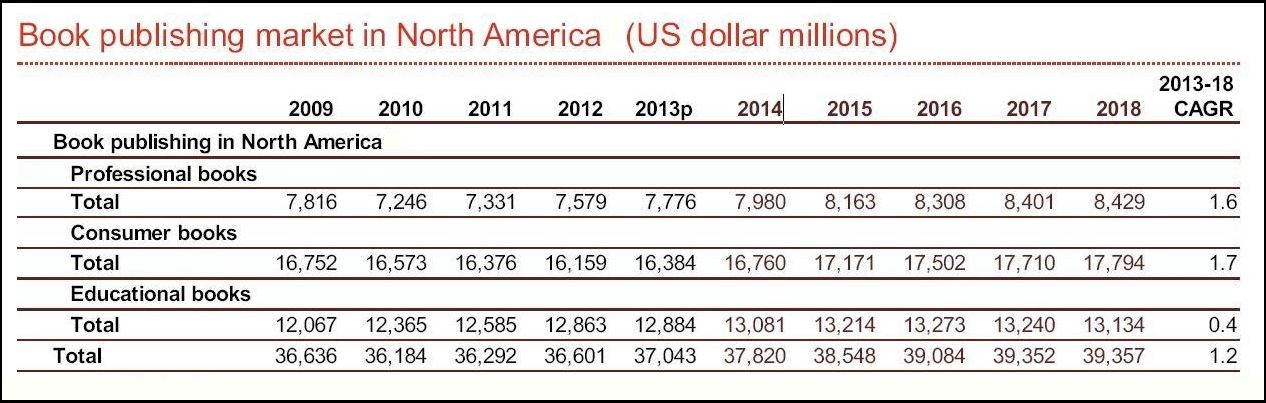

Another publication reviewing publishing markets in the late recession years is a 2014 PwC report, Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2014-2018.

This chart (Fig 3) shows sales across all book publishing sectors in North America. Sales are actual through 2013; projected thereafter. After a 1% drop between 2009 and 2010, growth resumes, but it takes till 2012 to mirror 2009 totals. Trade sales (“Consumer books”) decline slightly through 2012, and then start to head upward. PwC doesn’t define its data sources.

One concept I’ve wrestled with is the transition from sales growth to sales stagnation. What’s the difference between “our sales were up 5% last year, but are just holding even this year” versus “our sales declined 5% this year”? The latter is worse from an operational perspective, but looked at more broadly represents a similar trend. Growth stalled is the wealthier cousin of decreased sales; both can indicate a similar economic shift. The point: The book publishing industry grew steadily for many decades up until 2007. It took a hit for a few years. Growth since has been tepid. In the current euphoria over the resurgence of print, and the unanticipated audiobooks bonus, there’s not much discussion that most sectors of the industry seem stuck in neutral and one of the largest sectors, higher ed, is hurting.

Other Reports

Looking through general news coverage of the recession economics of book publishing over the last 30 years just one article sticks out. A 1990 New York Times article, “Jitters in a ‘Recession-Proof’ Trade,” provides two tidbits:

• “The Depression was a bloodbath for many publishers. ‘In 1929, there were 721 publishers with sales of $182 million,’ he said (William S. Lofquist, a famed publishing analyst at the U.S. Commerce Department). ‘But four years later, there were just 410 publishers and sales had plunged to $82 million.'”

• “Although there is a widespread belief that publishing weathered the 1981-82 recession well, figures from the Association of American Publishers show virtually no growth for trade book sales in that year, compared with an average of 13.3 percent in the years since 1982.”

Lofquist, mentioned above, prepared authoritative annual economic reports on the U.S. publishing industry from the mid-1980s through 1998. He documented an eight-month recession lasting from July 1990–March 1991. The news was never glum. 1990 sales rose 6.1 percent over 1989. The next year he reported “while the 1990-91 recession took its toll on most U.S. manufacturing operations, the book publishing industry forged new sales records in 1991.” Further, “U.S. bookstores recorded one of their best sales years ever.”

In the same report Lofquist pointed out that “while book purchases are derived from discretionary income, many U.S. consumers view books as providing an attractive cost/benefit relationship and are loath to permit recessions to impact negatively on their purchasing patterns.”

In his 1993 report, covering 1992 sales, he postulated that “the book industry’s brush with the 1990-1991 recession may well be over.”

Advice for Publishing in Hard Times

The one gem of a journal article that emerged from the 2007-09 recession is Peter Jovanovich’s Publishing in Hard Times (published April 2009). It’s well worth the $39.95 to unlock it from Publishing Research Quarterly‘s archives. Jovanovich, a publishing legend, is the son of another legend, William Jovanovich, of the one-time Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Peter Jovanovich was variously head of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, McGraw-Hill, and Pearson Education, and is now an advisor to private equity firms in New York. In Publishing in Hard Times he describes his “misfortune to labor through all sorts of downturns,” the worst being the 1974 recession, “when my employer Macmillan laid off 600 workers in one day.” But he recalls that even as a child he saw the impact of early recessions, when the sweaty “men in suits” would arrive at his family home “planning cutbacks in expenses and even staff because they sensed an impending downturn in the business.” The firm “successfully weathered each recession, by cutting back at the first signs of weakness.”

Publishers, he writes, “are by nature optimists,” which may explain why they “often realize too late that their entire industry has entered a prolonged slowdown.” His advice is that in a recession publishers should focus all their money and attention on finding authors, making products, and selling them. Layoffs are a necessity, sooner, rather than later, as “most of the costs are in people.” But product development and sales efforts must not be compromised: this is where growth will stem from when the economy inevitably improves.

Publishers, he writes, “are by nature optimists,” which may explain why they “often realize too late that their entire industry has entered a prolonged slowdown.” His advice is that in a recession publishers should focus all their money and attention on finding authors, making products, and selling them. Layoffs are a necessity, sooner, rather than later, as “most of the costs are in people.” But product development and sales efforts must not be compromised: this is where growth will stem from when the economy inevitably improves.

A Hits-Based Industry

As with movies, music, and videogames, book publishing is clearly influenced by big hits. Where in the movie industry a mega blockbuster can impact an entire year of ticket sales, the benefits of book publishing hits tend to accrue to the largest players, affecting their annual reports, but not much moving the needle on industry sales as a whole.

For smaller publishers a hit can have a disproportionate impact on overall sales. Richard Nash put it well when he was editorial director of Soft Skull Press. “For any given independent publisher, the effect of the success (or failure) of just a couple of books will far outweigh macroeconomic effects,” he said. “Our sales can seesaw pretty dramatically. Up 100% one year, down 40% the next, up 30% the following.”

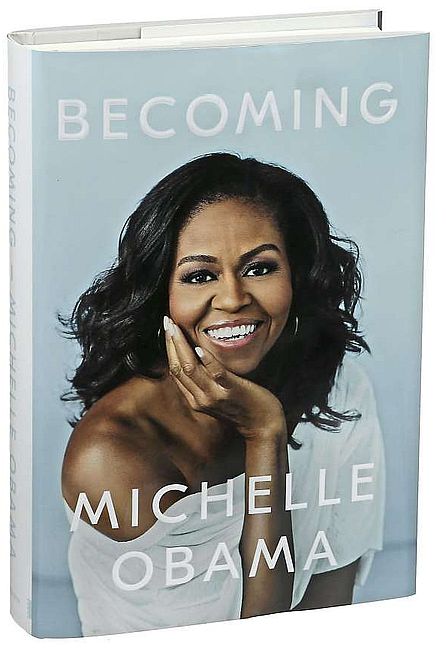

Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming, sold 3.4 million copies last year, producing some $50 million in sales for Penguin Random House U.S. This made a difference to PRH owner Bertelsmann, but it’s a plop in the bucket for a trade industry with $10.6 billion in annual sales.

Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming, sold 3.4 million copies last year, producing some $50 million in sales for Penguin Random House U.S. This made a difference to PRH owner Bertelsmann, but it’s a plop in the bucket for a trade industry with $10.6 billion in annual sales.

(By way of comparison, the movies Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War each grossed roughly $700 million in the U.S. last year: each of them representing 6% of 2018’s box office receipts. Musically, Drake’s album Scorpion was #1, selling 3.905 million “equivalent album units.” Total music industry revenues were $9.8 billion in 2018.)

This Time is Different

The proposition that “this time is different” is one of the most common mistakes made when pondering an economy overdue for a correction. As described in a book with this title, experts will claim “that the old rules of valuation no longer apply and that the new situation bears little similarity to past disasters.”

“Technology has changed, the height of humans has changed, and fashions have changed,” the authors acknowledge. “Yet the ability of governments and investors to delude themselves, giving rise to periodic bouts of euphoria that usually end in tears, seems to have remained a constant.”

It’s instructive to review Wikipedia’s “List of recessions in the United States.” Since the Great Depression there have been thirteen recessions, some lasting just six or eight months, the most recent lasting a year-and-a-half. The so-called “Great Recession” lasted from December 2007 till June 2009, and things went quiet for over a decade (setting a modern record), till the COVID-19 recession, which lasted only two months, from February 2020 – April 2020. That recession was the starting point for the great Covid book sales boom — publishers are delighted when people are forced to stay home.

Conclusion

The available financial data of the recessions of 1990-91 and 2007-09 shows only a modest impact on the U.S. book publishing industry, certainly in comparison with the larger economy and other industry sectors.

The publishing industry has changed in subtle ways since the recession of 2007-09. Back then ebook sales were growing fast. According to a Publisher Weekly article, “during the 2008–2012 period, trade sales overall rose a total of 14.2%, with the increase due entirely to the introduction of ebooks.”

Audiobooks sales are growing quickly this time around. In 2018 they reached 6.6% of total trade sales, while ebook sales still commanded 13%. By 2023 they represented nearly 10% of trade sales, versus 11.3% for ebooks.

A more important change may be the coming-of-age of online streaming media since 2007-09. Netflix revenue grew 35% to $16 billion in 2018. Last week Apple announced its new streaming service while Disney Plus will be launched in the fall. Book publishers will be competing head-on with these services in the next recession, and that may not be a pretty picture.

Most publishers have aggressively cut costs over the last decade; there’s not much fat left to trim. Printing costs have spiraled. The winners will surely be companies with access to capital, preferably from retained earnings.

I think the next recession will also shine a laser beam on metadata and online marketing. Once audiobook sales peak, which they inevitably must, enhancing metadata and concomitant online marketing strategies will become the only investment available to publishers with a near-certain ROI.

One way or another, prepare to fasten your seatbelts. Insert your suppositions into your predictions, then tighten by pulling on the loose end of the strap.

Notes:

* Greco, Albert N. The Economics of the Publishing and Information Industries: The Search for Yield in a Disintermediated World. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015

** Greco, Albert N., et al. The Book Publishing Industry. Routledge, 2014.

Dollar photo: Adapted from NeONBRAND on Unsplash

Glass half-full: S nova [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

April 2, 2019: A Harvard Business Review article “Companies Need to Prepare for the Next Economic Downturn,” includes the advice: “focus on technological competitiveness.” The authors point out that “technological progress will not stop during a downturn; neither, therefore, can companies afford to put their digital change agendas on hold.”

November 17, 2022. Long-time publisher Richard Charkin, in his article “Hard Times,” considers the lessons for survival for publishers in a tough economic climate.