March 1st, 2016

Catching up on my industry reading I’m facing the large effort required to try to digest the latest Author Earnings report and then wading into the vast cesspool of vitriol it engenders.

Many successful self-published authors give back to this publishing industry that has earned them fame and fortune. I divide them (very) loosely into three categories: First are those who share insights into the craft of writing. Second, those who share experiences about how to market your writing.

Many successful self-published authors give back to this publishing industry that has earned them fame and fortune. I divide them (very) loosely into three categories: First are those who share insights into the craft of writing. Second, those who share experiences about how to market your writing.

Then there’s a much smaller group, the vocal defendants of self-publishing’s merits in a world that sometimes appears to be operated by 5 big traditional book publishers in New York for their sole benefit, the rest of the industry be damned. The first two groups (although they often cross over in the types of advice proffered) are not my focus in this blog entry. I want to look at the third group, the self-publishing defenders.

J.A. Konrath was first out of the gate, expending gobs of energy arguing for the self-publishing choice and generously sharing stats and stories that gave credence to his claims. Numerous authors have followed in Konrath’s footsteps, creating a sort of self-publishing glee club, sharing, singing and selling. David Gaughran is one. Barry Eisler, Bob Mayer, Dean Wesley Smith, and Victoria Strauss (via Writer Beware) are among the others.

A few years back bestselling author Hugh Howey joined the ranks. He jumped suddenly to the head of the class in early 2014 when he teamed up with “the Data Guy” and created the website Author Earnings.

If I was trying to describe Author Earnings to someone outside the book industry I’d say:

The book publishing industry is sadly lacking for accurate, actionable data because the biggest retail player, Amazon, reveals next to nothing about its book sales. The five largest publishers are not much more helpful.

The organizations that gather sales data, notably the Association of American Publishers (AAP) and Nielsen BookScan are each hobbled, the AAP because it represents mostly the larger players in the traditional publishing industry, Nielsen BookScan because it can’t get Amazon’s data either.

So any attempt to assemble sales data, particularly Amazon sales data, is to be thoroughly welcomed. That’s the challenge that Author Earnings addresses. Every couple of months they pull together as much sales data as can be skimmed off Amazon’s site to try to pull together estimates of self-publishing unit sales and revenue.

Sometimes they provide a specific focus in a report, such as their October 2015 effort, with its “Apple, B&N, Kobo, and Google: a look at the rest of the ebook market.”

I’d probably have lost their attention by this point, but if they were still listening I’d add: And Author Earnings has become perhaps the most polarizing blog in the entire U.S. book publishing industry. Why? Because they focus on ferreting out the success of self-published authors. Which, of necessity, shines a light of where the big traditional publishers are losing market share. Which Author Earnings unequivocally expresses with disdain for the Big 5 publishing community.

What got me started with this post was Porter Anderson’s February 9 coverage of the Author Earnings report. As always a balanced reporter, Anderson doesn’t buy in 100% into the report, and at one point refers to its “partisan nature” and writes that “Author Earnings repeatedly has hobbled its own efforts to widen the discussion… by framing its results in ways that call out ‘the other side’.”

This earns him some verbose derision in the comments, all of which he handles with calm and grace. As he writes, “every time a rude, vulgar, spiteful comment is logged somewhere on these issues, it tells us much more about the commenter than about the people being attacked or the issues being trashed.” Yes, that’s true. But not every issue in our industry draws rude, vulgar, and spiteful comments.

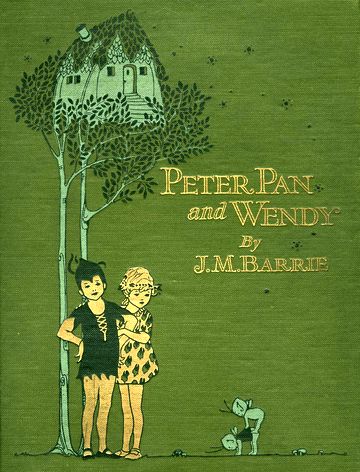

Every time a child says “I don’t believe in fairies”, there’s a fairy somewhere that falls down dead. —J. M. Barrie, Peter & Wendy (1911)

Writing and publishing books, like most creative endeavors, requires more than just a little faith in magic. In this sense it’s not dissimilar to religion. And it’s never wise to call out the faithful on the true nature of their gods.

What is most extraordinary to me is the extent to which this debate is polarized.

What is most extraordinary to me is the extent to which this debate is polarized.

It’s entirely reminiscent of (and I suppose a continuation of) the early days of Kindle ebooks (2007) where everyone lined up on one side of the school yard or the other: either ebooks were the greatest thing that had ever happened to readers and writers, or else they were hideous in appearance, full of errors, and who would want to read on that stupid $400 black and white ereader anyway?

So here we are nearly a decade later. Print sales have taken a hit, but not a crippling hit. And every day something like a million paid ebooks are downloaded from Amazon’s U.S. store. Beyond those sales are the other U.S. ebook sellers, the libraries, the free ebooks, and then, of course, there’s every other country in the world. No matter how you slice and dice it there’s something remarkable brewing in the book publishing industry.

Meanwhile, in the New Yorker, we have David Denby asking “Do Teens Read Seriously Anymore?” which calls on very limited data to conclude the “few late teen-agers are reading many books.” Has book buying become a zero-sum game, where one more self-published purchase is one less traditional buy?

Data is just something to bounce off of when you’re pulling together a strategy. Data is to be played with by marketers. What if Author Earnings’ numbers are off by 25%? By 50%? What then? Maybe they’re underestimated. What then would be the outcome? All data collection reflects a bias as does the interpretation of that data. There’s nothing new going on here.

I know authors who would rather sell one copy of their novel under the Knopf imprint than 1,000 self-published copies. Neither outcome will change their financial standing, but the former would greatly change their social standing.

The most interesting part of the February report falls in a section called “Amazon’s Print Book Sales… and the Law of Unintended Consequences.” I’ve argued before (as have others) that the large publishers pushed up ebook prices to protect print book sales. Book displays in 600 Barnes & Noble chain stores and thousands of independent bookstores are something that large publishers can buy and control. The only way to land on the front table at the Amazon store is to be the #1 bestseller. Traditional publishers, for the first time, are facing clear competition in the bestseller department and have no control over their largest reseller.

Hugh Howey and the Data Guy point to their newly-collected print sales data and posit that by pushing ebook prices so high print prices at Amazon were increasingly attractive. And they were more attractive at Amazon than they were at most bricks and mortar bookshops. As Amazon comes close to perfecting the cost/benefit ratio in its delivery and customer service programs the bricks and mortar option is less and less appealing. I’ve already reported on declining book sales at Barnes & Noble. Canada’s Indigo claims book sales continue to increase, but as a percentage of total chain sales they’ve declined from 69.8% in 2013 to 57.8% in the latest quarter.

If the impact of increased ebook pricing in driving readers increasingly toward self-published authors and away from bricks and mortar retail then the industry is shooting itself in the foot.

Perhaps it’s the backstory that makes Author Earnings so disliked by the publishing industry. In large part it’s religion, I’d argue, that makes Author Earnings so popular with self publishers. Oh, yeah, and also because they’re producing such beguiling and important insights.

Postscript: Mike Shatzkin’s February 29 blog entry throws a new element into the mix. Declaring that it’s “the first time in seven years of writing this blog that I have walked back the thrust of a whole post” he quotes an unnamed “powerful literary agent” and “people in a position to know” that the high ebooks prices from the big 5 publishers are there at Amazon’s insistence in order to gain a higher margin on those sales. And further, these prices have not altered the decline in print sales.

The reaction to Mike’s claims has not been positive. It’s worth reading the comments — a testy bunch, drawing ill-tempered retorts from Shatzkin. More interesting is Passive Guy’s blog commentary on Shatzkin’s post (and another slew of comments below). As Passive Guy notes, “Since when has Amazon been obsessed with margin?”

The whole hullabaloo is starting to feel like a needless distraction.

Postscript 2: “While adult ebook sales had been pretty stable through most of the year, the trend that started in September (with sales falling almost 8 percent) deepened in October, as adult ebook sales of $83.6 million were down $23.7 million — or 22 percent — compared to the same month a year ago [as tabulated by their pool of approximately 1,200 publishers].” (This is from Publishers Marketplace, by subscription only. The AAP data is covered by PW here.) Is there another credible explanation for this precipitous drop other than rising prices?

Postscript 3 (March 10): Passive Voice blog has a good commentary on Porter Anderson’s article covering Data Guy’s presentation at Digital Book World. Passive Voice notes: “It sounds like (Data Guy) was able to accomplish in person what the voluminous statistics and analysis he and Hugh Howey created with Author Earnings could not do – convince an audience oriented toward traditional publishing that AE provides very useful information about ebook sales.”