January 15th, 2013

I’ve been working with Michael McGill, a smart student from Pace University’s Masters of Publishing program. Mike has been spending a lot of time researching and documenting a truly tough challenge: the ROI from developing and maintaining metadata for books. Mike presented his report to attendees at the 2013 Digital Book World Conference in New York and authorized me to preview his work in this blog.

Not only is the ROI for book metadata inadequately defined, the ROI for investing in any type of metadata has been examined with only a glance.

The book industry was fortunate that Nielsen took a solid stab at the challenge a little over a year ago. At last year’s Digital Book World Conference Nielsen CEO Jonathan Nowell presented a white paper: The Link Between Metadata and Sales (PDF).

I reviewed the paper in a couple of blog entries last summer. I felt that the report ultimately reveals less than was promised. The major conclusion to be drawn about the impact of basic (core) metadata is that book covers sell books online as surely as they do in a bookshop.

Nielsen then considered four categories of enhanced metadata: the short description (350 characters), long description, review, and author biography. While these elements certainly impact sales, the report is challenged to define exactly how — and how much — this occurs.

Still this is a worthy first attempt to pin down metadata ROIs. And it was to this same data that Michael McGill returned to for his study, The Supply and Demand of Metadata Competency in the Publishing Industry.

The problem with the conclusions in the Nielsen report lies mainly with the ad hoc nature of Nielsen’s metadata categories. It’s not Nielsen’s fault. Nielsen focuses on two classes of metadata, BIC Basic and Nielsen enhanced. BIC Basic is defined by the U.K. industry association Book Industry Communication (BIC), the equivalent of Book Industry Study Group (BISG) in the U.S. and of BookNet Canada. BIC Basic is designed to enable ecommerce but not specifically to serve as a useful sales data set.

Basic could be an acceptable general category, including items such as title, author, ISBN, price and territorial market rights. But it also includes “jacket/cover image.” When a metadata record includes a cover image sales increase by some 800%, throwing off the calculations for the other basic data.

Likewise “enhanced” is not all of what one might expect: short description, long description, review and author biography. Curiously the presence of one or two of these elements led to decreased sales in bricks & mortar locations, but increased sales online.

Nielsen makes few distinctions in terms of bestsellers versus mediocre sellers, frontlist versus backlist, nor any real attempt at a control group against which to measure the results.

Michael McGill’s contribution to understanding the impact of metadata on book sales has two aspects. First of all he recasts the Nielsen study results into more useful containers. Secondly he correlates the study data against a wider set of publishing industry measures, namely total industry revenue, percentage of sales online, fiction versus non-fiction sales, percentage of sales from backlist versus frontlist, as well as publishing industry operating margins.

McGill calculates that the U.S. trade publishing industry could grow by as much as 3.2% just by supplying the missing metadata from the titles available today, for a total of just over $400 million per year (based on 2011 sales data).

Print book sales for 2012 as recorded by Nielsen BookScan were down 9.3% compared to 2011 (and those sales were down 9.25% from 2010). In these circumstances this relatively accessible sales boost would have to be most welcome.

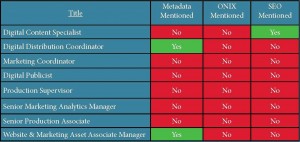

The other compelling aspect of McGill’s study is his exploration of the HR (human resources) issues that appear to underlie the publishing industry’s failure to offer full sets of title metadata. An examination of job postings that would include metadata responsibilities reveals that the industry is failing to articulate metadata skill requirements.

Masters of publishing programs such as the program McGill enrolled in at Pace University have now identified metadata skills as an important addition to their curriculum. Yet publishers are not specifically searching out graduates with these skills. Their departments are not being appropriately staffed.

The preparation and management of book title metadata is failing at multiple levels. There’s no question that the degree of complexity is far beyond nearly every other present publishing practice. The only other area of similar complexity is ebook production to the level of current industry standards (including EPUB 3 and KF8). The industry addresses this challenge mainly by farming production out of house to dedicated service providers.

Metadata transmission can be easily entrusted to reputable third parties. But the preparation of accurate metadata must remain an in-house process. Metadata change throughout the lifecycle of a title. And the latest code definitions in ONIX 3.01 encourage publishers to cast their nets wide to capture a robust set of relevant data. This demands a level of awareness achievable only through training, a scarce commodity for book publishers.

Our own Metadata Handbook provides an introduction to the challenge, one that can address up to intermediate requirements. But advanced metadata usage is understood by perhaps only a few dozen people in the entire industry (and none better than Editeur’s Graham Bell, Chief Data Architect for the group).

Michael McGill has taken an important step toward calculating the ROI available to publishers that undertake the metadata challenge, while also defining the scope of the HR requirements that good metadata demands.