June 13th, 2012

Trying to make a book truly discoverable can lead authors and publishers toward a world of pain. It’s not so much how do you find a needle in a haystack. It’s why would you even bother.

“Findability” is the kinder, gentler problem. How do you find a needle in a haystack? As it happens, the haystack has been indexed, and provided you don’t spell it kneedle, you should be in luck.

I described the difference between findability, discoverability and marketing here, and then provided a couple of examples of findability challenges here.

What is the sound of an unfound book? Until now I’ve conveniently ignored that findability is merely a state of being until its better half shows up at the party, namely someone who’s searching for your book. It’s that magic moment you’ve been waiting for since you began writing. A well-heeled buyer hears the news that your book is solid, well worth the $2.99 price tag you’ve splayed on the bitmapped cover. They’re ready to purchase.

They must first seek so that they can find. To seek they will search. To search they’ll use a search engine. There’s a significant risk that they will fail to find your book simply because most ecommerce search engines don’t hold a candle to Google (and sometimes Bing and Yahoo) for delivering accurate results.

Here’s a case study: Let’s say that last weekend you read in The Guardian Jay McInerney’s glowing tribute to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic third novel, The Great Gaby. Well that’s what you thought he wrote, as you remembered it a couple of days later: The Great Gaby, not The Great Gatsby.

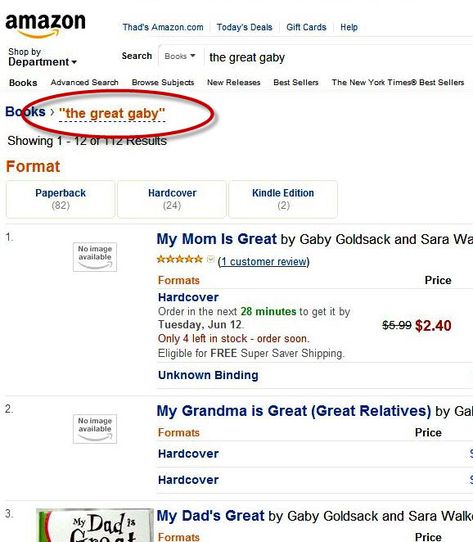

So you head over to Amazon, because it starts with the letter “A” (you’ll go to Barnes & Noble next). You search for the title:

…and a whole bunch of books by authors named “Gaby” appear.

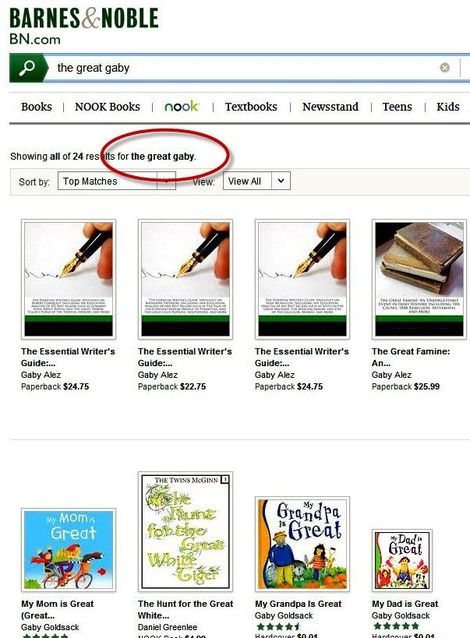

Next you try Barnes & Noble:

More Gabys.

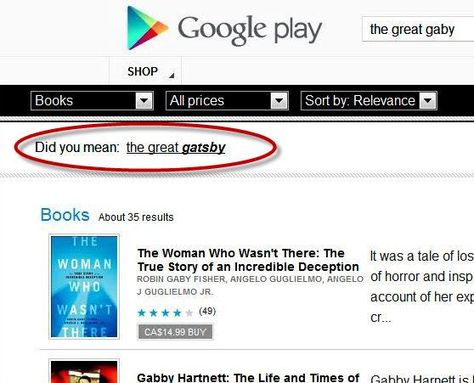

In frustration you attempt a Google search:

Did you mean “the great gatsby” Google posits. You click on that.

Yes, you did. Even Google Play, not ordinarily your first choice in online shopping, suspects it’s The Great Gatsby you’re looking for.

Understanding Search Engines

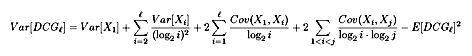

In his 2007 research paper, Evaluating Search Engines by Modeling the Relationship Between Relevance and Clicks, Ben Carterette provides a mathematical formula for evaluating search engines:

If you find it useful, please get in touch.

The challenge for search engines is more simply stated by Michael Berry and Murray Browne in their 1999 book Understanding Search Engines: “Basically we are asking the computer to supply the information we want, instead of the information we asked for.”

This then is the challenge of findability.

If you have the correct information (including the spelling) of a book title, you will probably be able to locate it. If you have the correct spelling of the author’s name, and if that author’s name is more unusual than “J. Smith” or “M. Chang”, you’ll likely find a listing of their published work. And, no matter what information you’ve got, use Google as the first stop on your search journey (or you can try Bing or Yahoo, which also pass The Great Gaby Test.)

A Panda Born in Mountain View, California

The story of online search will be measured as BP and then AP: Before Panda and After Panda. Panda is the name given to the changes Google implemented to its search algorithm at the beginning of 2011. Panda effectively put an end to the game of gaming Google.

We’ve all heard about SEO – Search Engine Optimization – the “science” of trying to make sure that your web site, your app or your book shows up in the top of Google’s search results. BP, Before Panda, the science of SEO involved a lot of aptly-named “black hat SEO,” tricks that exploited gaps in search engine algorithms. There was a broad range of effective black hat techniques, though most of them involved some variation on fake inbound links to the promoted web site. With a flourish of very advanced algorithmic magic, which Google has plenty of on staff, the gaps were closed. In April of this year Google slammed the door extra tight with another update, this one named Penguin.

Shifty SEO salesmen will still try to sell you some SEO snake-oil, but the days of black hat search magic have passed. They might hem and haw in obscuring what took place in their once very profitable and productive industry. But it comes down to something very simple: Google search now rewards quality: rich descriptive information delivered with a near-psychic ability to divine your search intentions. Go ahead: try and stump Google. I dare ya!

You’ve perhaps heard of the Flying Wallendas. You will not yet have heard of the Searching McIlroys. With my elder sisters Anne and Sue we formerly guaranteed answers in 15 minutes. We’ve now got it down to 5. And as soon as I post this blog entry, a search on “the Searching McIlroys” will bring you to this blog entry, and not to that golfer fellow Rory, who in April, after a big loss, told his mum “it’s only a game.”

Metadata & Findability

The conclusion I reach about metadata and findability is two-pronged. As the previous post demonstrated, if the record is not available online, the book or the recording or the author does not exist; they cannot be found. As demonstrated above, even simple spelling errors will trick an average ecommerce search engine, creating a different sort of invisibility.

Missing metadata makes books invisible. And if you’re uncertain of your search terms, your best bet is Google, The Pseudo-Psychic Search Engine.

August 9, 2012: Just now I was looking for books by Barbara Ehrenreich and typed my best guess “barbara ehrenbach” into Amazon, Books, and got back “Your search ‘barbara ehrenbach’ did not match any products”. Typed the same thing into Google and the first result was an article by Barbara Ehrenreich in The Huffington Post.