September 22nd, 2020

In last Sunday’s New York Times there’s a wide-ranging profile of Madeline McIntosh, chief executive at Penguin Random House, the largest trade publisher in the U.S.

The article is by Alexandra Alter, who writes about publishing and the literary world for the Times. I was pleased when she asked me for a few observations on the marketplace of which Penguin Random House has become such a key part, perhaps an overwhelming part, in a publishing industry that appears to be increasingly concentrated in just a few hands.

Publishing Concentration

The issue of corporate concentration in publishing is an old one, dating back at least to the 1970s. Ben H. Bagdikian presented a paper called “Conglomeration, Concentration, and the Flow of Information” to the Symposium on Media Concentration at the Federal Trade Commission in December, 1978. In it he pointed out that “twenty corporations control 52 percent of all book sales.”

André Schiffrin’s The Business of Books: How the International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read, published in 2000, notes that “six behemoths share 80% of the market,” while warning of “the danger to adventurous, intelligent publishing in the bullring of today’s marketplace.”

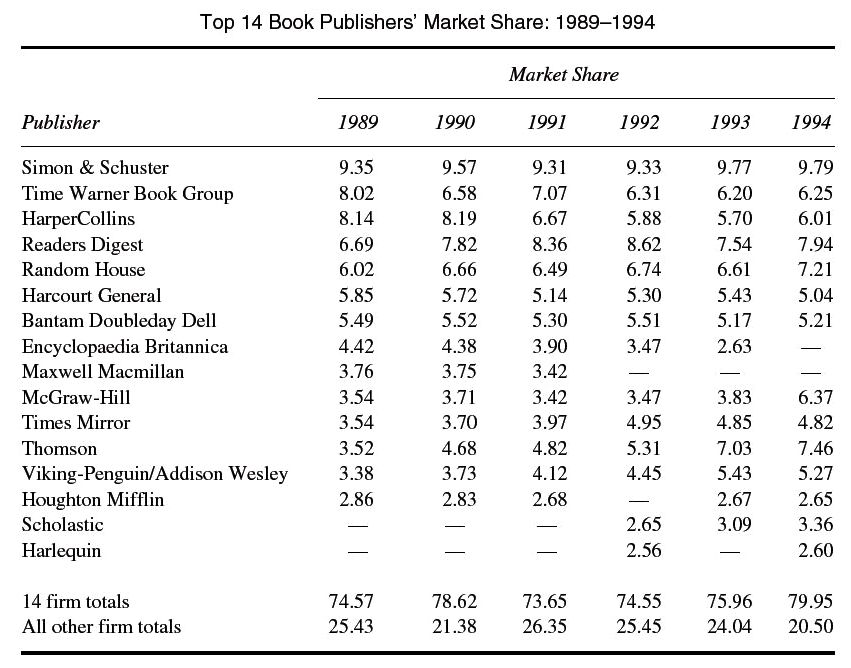

A lot of data has been compiled over the years about corporate concentration in publishing. Here’s one chart from Albert Greco’s study, The Impact of Horizontal Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Concentration in the U.S. Book Publishing Industry: 1989–1994:

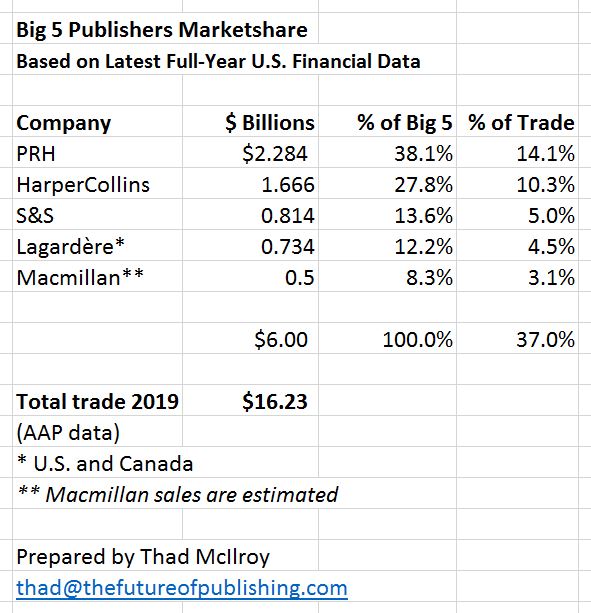

There’s no apples-to-apples comparison with more recent data — so many of the firms from 1994 have disappeared, mostly via acquisition into the current Big 5. Several others, like Encyclopedia Britannica and Scholastic, are in a different orbit; others are part of the educational and professional publishing segment, like McGraw-Hill and Thomson (now Cengage). But even without those, the largest trade firms held something like 55% of the market in 1994. Another chart, found in John Thompson’s Merchants of Culture, shows the Big 5 (adjusted for subsequent acquisitions) with 52.2% of the U.S. market in 2008. My rough calculation shows the Big 5 now with 37% of the trade publishing market, based on the latest data (current to what’s been reported during the summer of 2020).

With all of the usual provisos associated with financial data, concentration appears to have in fact eased slightly overall. I could burrow down further on this notion, but the source data, for various reasons, can be unreliable for drawing strong conclusions. I’ll leave it as a broad generalization.

The Bestseller Syndrome

Alter also notes Penguin Random House’s continuing domination of the bestseller lists. That domination seems certain to be extended this fall with the publication of Barack Obama’s memoir, A Promised Land, part of a $65-million-plus deal that included Michelle Obama’s 2018 multimillion copy bestseller Becoming. One of my comments to Alter was that, arguably, none of the others Big 5 publishers could have pulled off this deal, not because of the price tag (there were multiple bidders), but because of Penguin Random House’s international network across English-language publishing, as well as in Europe and South America.

The relentless focus on the next bestseller is also an old topic when analyzing trade publishing. Thomas Whiteside critiques the trend in his The Blockbuster Complex: Conglomerates, Show Business, and Book Publishing, published in 1981. One reviewer noted that Whiteside found “the quest for the blockbuster is both an enterprise and a state of mind that is occasionally unseemly and potentially socially pathological.”

Leonard Shatzkin, in his 1982 book, In Cold Type, refers to the “the bestseller syndrome that is now so prevalent” in book publishing and the “odious bestseller emphasis that already plagues the industry.”

David Garvin’s 1981 article, Blockbusters: The Economics of Mass Entertainment, defines sales over one million copies as a typical sign of a blockbuster. He describes the trend thusly:

In order to reduce… uncertainties, and to reduce the variance of their profit streams, firms in the entertainment industries have chosen to invest heavily in well-known performers… The pursuit of blockbusters, once a rarity in the entertainment industries, is now widespread… While these projects seldom achieve high returns on investment, they rarely incur large losses. Occasionally, however, they succeed spectacularly, generating enormous profits which more than compensate for the poor showings of other offerings.

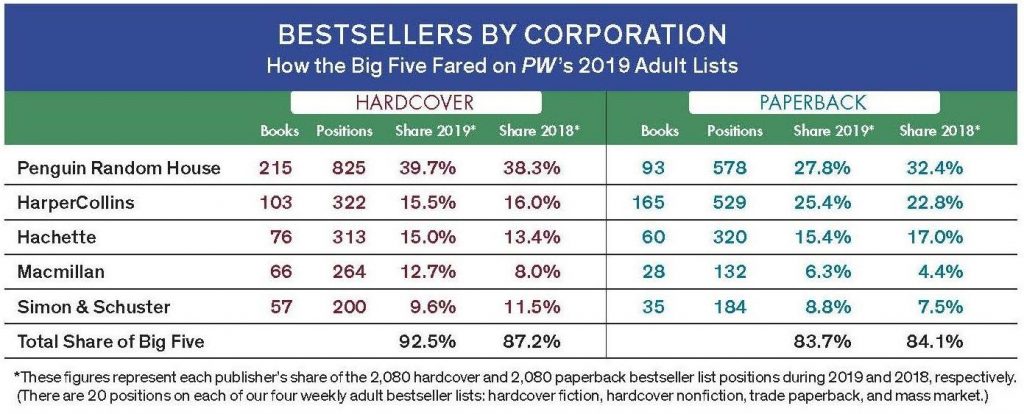

From my perspective, “share of blockbusters” might be a more telling metric than marketshare from overall sales. There are leading indicators and there are lagging indicators: current success on the bestseller charts points to good things to come. I thought the title of Alter’s article captured the spirit here: “Bestsellers sell the best because they’re bestsellers.” And, I would add, the best authors are attracted to the publishers with the most bestsellers. Here’s a chart from the January 20, 2020 issue of Publishers Weekly looking at bestseller marketshare.

Penguin Random House’s share of hardcover bestsellers is significantly larger than its marketshare by total dollar sales.

If I was an agent, I would routinely submit my top titles first to Penguin Random House, and if I was an author, I would accept a lower advance from Penguin Random House than I would from all competitors — knowing that, with the company’s power and distribution prowess, I’d pick up even more cash from the royalties paid on the back end.

Now that is publishing power, power that’s not easily dislodged, power that lasts.

Comments

Juzgando la editorial por sus bestsellers – Actualidad Editorial

Sep 28th, 2020 : 11:56 PM

[…] cultura empresarial del bestseller ha adquirido en la industria editorial que, en su artículo “The power of Penguin Random House”, Thad McIlroy propone una calificación de la importancia de los grupos editoriales no sólo por […]