January 9th, 2018

Over the holidays I received an inquiry from a journalist about book buying, was it more of an impulse or a plan. What’s the breakdown? Seemed like a simple enough question. From my studies on book buying I knew that the impulse percentage was fairly high, higher than many would expect. We want to think that shoppers are rational animals, particularly when it comes to high-brow purchases. Don’t they think carefully before they buy a book?

Well, no, they don’t. The most pertinent data I could uncover (Barnes and Lorimer, 1997) showed that about 60% of books bought in bookstores are impulse buys.*

By happy coincidence I then landed on an article from PwC, How Tech Will Transform Content Discovery. It’s an introduction to a timely and trenchant report, Can you find that show I didn’t know I wanted to watch? (PDF). Using a (credible) representative set of respondents, the report looks specifically at the digital discovery of video (and more specifically at TV shows and movies). The focus is on Pay TV and streaming video, not on theaters. How effective are personalized recommendations? How can they be improved? How does the discovery of video content compare to the discovery of other types of media?

The questions addressed include:

- Is digital discovery of video still hard for consumers?

- Are consumers overwhelmed or overjoyed by choice?

- How influential is social media in the discovery of content?

- How can personalized recommendations be improved?

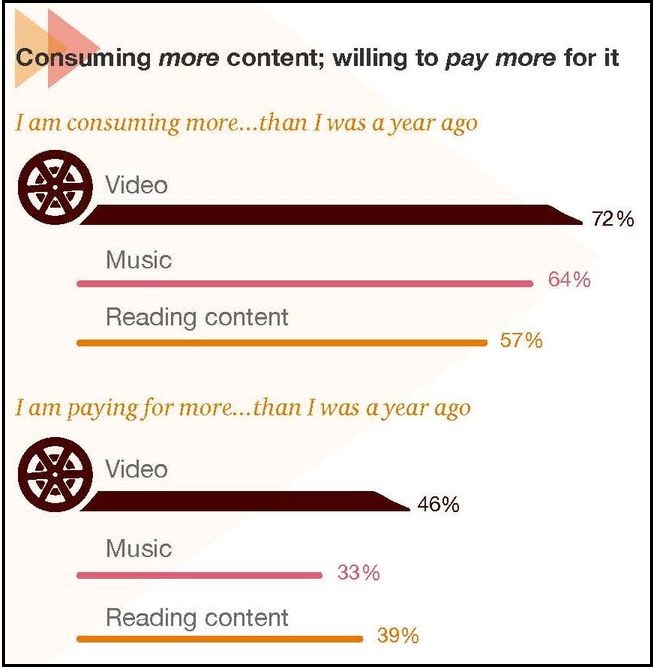

All respondents are consuming more content than a year ago, 72% more video and 64% more music. But surprisingly (shockingly?) 57% said they were also reading more content. And they’re paying significantly more for content than they were the year before.

62% struggle to find something to watch

Despite the hundreds of available TV series available to watch right now, and the many thousands of movies, nearly two-thirds (62%) agree that they often struggle to find something to watch. Two-thirds are watching new content versus something they’ve previously seen, while half are just browsing and discovering new content rather than tuning into something they knew they wanted to watch.

50% are frustrated finding a video to watch. Surprising to me, next up is 37% who are frustrated trying to find something to read (32% for listening).

Discovery

No surprise: social media has a big influence on what content gets consumed, but for video watchers, the streaming services themselves are often the primary information sources behind the viewing decision, with their various “new on xx” and “top picks” listings. But “a recommendation from someone I know, either directly or on social media” is a major factor. 73% believe their friends and family know them better than their streaming service.

Aimlessly browsing is a primary way consumers find content

The question “thinking of a new TV show you watched recently, why did you choose to watch it?” is the video equivalent of the impulse book buy I describe at the top of this post. Nearly half responded “I came across it while browsing for something to watch and thought I’d like it” although ads, reviews and recommendations from friends all played a factor.

How can content producers become more persuasive?

Consumers want to know more before they buy. They want to know why a show (book, song) is highly-rated or slammed. Some responded “let me click through to reputable critics’ reviews directly from platform.” But friends always matter. Respondents said that they want “direct recommendations from people I know” and to see if “anyone I know is watching a show or movie at a given time.”

It’s essential to prioritize and harness metadata

I always make a distinction between “findability” — being able to find what you know you’re looking for, and “discoverability” — stumbling on the delightful surprise you didn’t know about. The report calls findability “search,” It’s “when you know what you want to watch, but can’t find it because the content is fractured across so many different platforms or because the search tools in the app are poor or frustrating.” “Discover” they define as “when you don’t know what to watch and someone (or something) recommends a new show to you that you might like but didn’t know existed.” The solution to both challenges is better metadata, they say, better structured, and more targeted. Better metadata aids in content generation, curation, archives/classification, distribution and audience targeting.

Moody consumers

A response that startled me was how much mood impacts content choice. 80% said it was a key influence. Now that’s a data point that escapes most of today’s recommendation mechanisms. It makes sense when you think about sitting down with a movie after dinner. If you’re in a grouchy mood a comedy is just right. In a better mood you might be willing to take on that challenging documentary. How can we translate that into selling books? How much would mood detection move the bookbuying needle?

The report (linked above) concludes with a series of five recommendations on how to get better recommendations to consumers. More data, better data, adaptive data, timely data, more reviews: for all content producers, the combination of too much content splayed against too many other digital distractions means that mastering metadata is the only way to win the content game. Definitely worth a read.

* Note: The question posed was very specific: books bought in bookstores, not books bought at retail other than in bookstores, book purchased online, etc.

May 30, 2019: A post on Publishers Lunch (paywall) today reveal an interesting supplemental data point: “…ceo of Readerlink Dennis Abboud noted that “in the stores we serve, 77 percent of the [book] sales are made on impulse.” Readerlink is “the dominant distributor of books to major nonbookstore retailers,” so it makes sense that the buyers they serve would not ordinarily go into a grocery store or an airport shop with a specific title in mind.

In the same post on Publishers Lunch, Barnes & Noble’s chief merchandising officer Tim Mantel said “we found the vast majority of our customers come into our stores with a single title in mind” — although that doesn’t preclude that these same customers would make an additional impulse buy during the same store visit.

June 22, 2019: Tonight I discovered a 2000 paper by Catherine Sheldrick Ross called “Making Choices: What Readers Say About Choosing Books to Read for Pleasure.” In it she reports that: “Readers overwhelmingly reported that they choose books according to their mood and what else is going on in their lives. Short books, easy reads, and old favorites are picked when the reader is busy or under stress. At such times, rereading a childhood favorite is the quintessence of comfort reading. More demanding and unfamiliar material is chosen when the reader’s life is calmer.” Her study focused on the “10% of the North American population who show up in national reading surveys as “heavy readers” — those who read upward of a book a week.”