August 5th, 2014

How to Succeed in Business by Bundling – and Unbundling is a thought-provoking interview with Marc Andreessen and Jim Barksdale online at the Harvard Business Review. Marc Andreessen was the co-founder of Netscape. Jim Barksdale is a veteran of IBM, FedEx and AT&T Wireless “brought on a few months after Netscape’s founding to provide adult supervision as its CEO.” Both are now tech company VC investors. Barksdale, in his early 70s, is one of those rare executives whose advice reflects a depth of experience, much longed for in this age of the “serial entrepreneur.”

One of Barksdale’s (many) well-known quotations is that “There are two ways to make money in the software business: bundling and unbundling” (there are several small variants on the quotation). The Harvard Business Review interview focuses largely on the music industry. Long playing records (LPs) launched the music business model of aggregating about 45 minutes worth of music, usually 10-12 songs onto one “carrier”. The model carried through to cassette tapes and then to compact discs (CDs). Launched initially by Napster, Apple’s relentless marketing of the one-song-per-file format “unbundled” the then-dominant CD model. After a decade of MP3 downloads the industry is once again “bundling” into streaming services like Pandora and Spotify.

The TV, cable and movie industries are undergoing an unbundling/re-bundling transformation through services like Netflix and Hulu, as well as pay-per-view online.

Magazines and newspapers are still struggling to find an unbundled business model and remain married to brands that matter far more to their proprietors than they do to readers.

Which brings us to books.

Books were never bundled in the way that songs were. It didn’t make sense. They were never restricted to a single broadcast channel, like TV networks and later, cable. OK, short story collections are sold as a bundle. But no one thinks that short stories represent an MP3-style opportunity. It’s easy to access single chapters on Safari, but Safari’s pricing uses an all-you-can-eat model of monthly and annual subscriptions.

At the end of July Macmillan announced that it “will be adding its full collection of frontlist eBooks to their public library e-lending pilot” and it became the final one of the “big five” U.S. publishers to allow libraries to offer all the titles in their ebook collections. It marked a milestone for libraries and ebooks. At the same time the pricing models for libraries are all over the map, ranging from a “one-user, one-ebook model license expiring after two years or 52 loans” to a “non-expiring, uncapped license costing 300% over retail on new ebooks.”

IFLA, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, just released a valuable report on ebook lending, the “IFLA 2014 eLending Background Paper.” The report considers the competition to libraries from the new ebook subscription services. It notes that “As far as trade ebooks are concerned, such services present a serious challenge to the role of libraries as the bundling services are more likely to view libraries as direct competition. The tension between commercial content providers with a profit motive and libraries with a free access to information motive will intensify when the service provided, a large curated collection of ebooks, appears to be the same.” I’m an unabashed public library supporter and this is cause for concern.

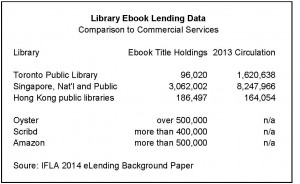

The report provides partial data illustrating ebook offerings from libraries posed against the commercial services (see chart).

Compare the top 25 titles at the Toronto Public Library with Scribd’s International Bestsellers and with Oyster’s New York Times Bestsellers (which apparently means any NYT bestseller, most likely from the past, as far back as the year 2000) and with Amazon’s top titles from its Kindle Owners’ Lending Library. Um. There’s not really a comparison if the metric is the range of current bestsellers. Libraries receive a bad rap for long waiting lists for top titles but the “available now” selection of the top 25 titles the Toronto Public Library still offers an appealing list of current titles.

Compare the top 25 titles at the Toronto Public Library with Scribd’s International Bestsellers and with Oyster’s New York Times Bestsellers (which apparently means any NYT bestseller, most likely from the past, as far back as the year 2000) and with Amazon’s top titles from its Kindle Owners’ Lending Library. Um. There’s not really a comparison if the metric is the range of current bestsellers. Libraries receive a bad rap for long waiting lists for top titles but the “available now” selection of the top 25 titles the Toronto Public Library still offers an appealing list of current titles.

As the controversy continues over pricing models for ebook lending it’s worth seeing if the pricing models of other streaming content businesses provide guidance to book publishers.

Netflix: “We generally license content for a fixed fee and a defined time period with payment terms varying by agreement.” Not much help.

Music streaming: “Nielsen says the average royalty rate per stream in the first quarter of this year was 0.5, up 33 percent from 0.375 a year earlier.” Not enough money.

Laura Hazard Owen reports that once a reader completes a certain percentage of a book [reported elsewhere as at least 10%], the publisher is paid “the same amount as it would receive if the book were sold through a regular retailer”. As Hugh Howey notes these services will appeal most to heavy readers: why would an occasional book reader spend over $100/year to subscribe to a large (though limited) selection? I agree with his analysis that the only way they can make money is by decreasing the payments to publishers. And publishers aren’t very likely to accept a major reduction in royalty rates. At least not until the service can prove that they are bringing new revenue sources to the table through discovery or by engaging occasional readers.

Amazon is not going to surrender this space to competitors. Scribd already had a business before trade ebook subscriptions while Oyster is solely dependent on the trade subscription model. Scribd has received nearly $26 million in venture capital; Oyster $17 million, the bulk of it this year. Goodreads had only $3 million in funding when Amazon bought it for $150 million. Oyster is “hot” right now and Amazon would be lucky to snag it for less than $300 million. Is it worth that much for Amazon to kill a subscription competitor? That’s the equivalent of the one-year revenue from two-and-a-half million $120/year subscribers. With Apple’s recent pricey purchase of Beats Oyster might offer better value to Apple rather than if it started an ebook subscription service from scratch.

Unbundling. Bundling. Does bundling ebooks into a subscription model offer enough advantages over a public library to justify its $10/month cost? Does it offer better value than just buying the books you want? Will publishers support it with pricing that make these businesses viable? Or will Amazon’s Kindle Owners’ Lending Library just wipe its competitors off the map?

Lots of questions; not enough answers.

August 12, 2014: The Wall Street Journal offers a similar evaluation, along with a bestseller list title-by-title comparison.

September 15, 2014, Publishers Weekly: Oyster Looks Back at a Year of E-book Subscription

September 16, 2014, Juli Monroe at TeleRead points out that only Kindle Unlimited works on eInk devices. This is a major limitation because stats show that some of the heaviest ebook readers still use eInk readers.