November 12th, 2025

This is a 4,000+ word blog post. It can take 20 minutes to read, aka, an eternity. I apologize.

I’ve been working on AI licensing issues for over a year now, and I wanted to share some of what I’ve learned.

Here are the topics I’ll cover:

- Licensing for AI: Understanding the landscape and the issues.

- A look at licensing deals to date.

- What are the big AI companies looking to license?

- Which companies and services can help publishers pursue licensing?

- The limits of licensing the news.

- Answer engines and the search for perfect information

- How important are books as information sources?

- Two types of training: LLM training and RAG.

- The Anthropic agreement.

- How much money is involved?

- Does licensing make content visible?

- Can the industry unite on the AI licensing challenge?

Introduction

In November 2024, an unnamed AI company* offered HarperCollins $5,000 for the AI training rights to a 350-word illustrated children’s book, Santa’s Husband, by Daniel Kibblesmith. It’s a “clever yet heartfelt book that tells the story of a black Santa, his white husband, and their life in the North Pole.” The author, who would have shared half the proceeds, turned the offer down via social media, not because of the cash value, but because the prospect of licensing his work for AI model training was “abominable.”

In November 2024, an unnamed AI company* offered HarperCollins $5,000 for the AI training rights to a 350-word illustrated children’s book, Santa’s Husband, by Daniel Kibblesmith. It’s a “clever yet heartfelt book that tells the story of a black Santa, his white husband, and their life in the North Pole.” The author, who would have shared half the proceeds, turned the offer down via social media, not because of the cash value, but because the prospect of licensing his work for AI model training was “abominable.”

—————————

In these end times, it’s been instructive to watch publishers, and, nearby, authors and their agents, try to come to terms with the AI beast. They hate it instinctively, of course they do, but they are starting to realize that some sort of engagement may be necessary. This is framed as “licensing.” Rights holders try to include restrictions around license terms, but once your content is part of the training data, it’s an all-or-nothing proposition, a land of no return. Should we opt in?

It’s a Sin

I often try to imagine how authors and publishers would be thinking, and feeling, about AI today if those careless software programmers had not grabbed the Book3 corpus, or downloaded pirated books from Library Genesis (LibGen) and Pirate Library Mirror (PiLiMi), and then tossed the books into the training of several of the largest AI models.** Let’s not drill down on all the details here, but that’s how some of the large language models got hold of copyrighted books. And so the lawsuits commenced.

Michael Barbaro, co-host of The New York Times The Daily, in a podcast with AI reporter Cade Metz, referred to this as “AI’s original sin.” While the old saying has it, “hate the sin, love the sinner,” many authors and publishers hold a passionate hatred for both. Will licensing help them move beyond their trauma?

The Land of Inchoate Fears

What is it, exactly, that authors and publishers imagine will be the long-term impact of generative AI on writing and publishing? Why are they so terrified?

The imaginings stem in part from their anger. As one industry player put it to me, “Authors feel that the AI companies have not just broken into their homes — they then kidnapped the children.”

Authors suspect that all of their books have already been purloined by the AI companies. It may not be all the books, and not by all of the companies, but, at least in the case of Anthropic, it’s apparently as many as 7 million digital book files.

An even larger fear seems to be that at some point generative AI is going to be good enough to write books that the public will purchase, instead of their own, and part of its ability to do so will stem from the books that have already been ingested.

You don’t have to play with the clumsy verbosity of ChatGPT and its siblings for long to dismiss that concern in the short term, but you don’t have to play with the latest versions of Claude.ai for long to recognize that there’s a basis for the fear. It could happen. And then what?

And What of AI More Broadly?

Anyone whose head is not buried in the sand can see that while content theft may be AI’s original sin, there’s just so much more at stake.

We could start with the environmental impact of generative AI. Problems of bias both in text and in images. Problems with believable fake nudes, and worse, child pornography. AI scams are everywhere, with the elderly being particularly vulnerable.

In a recent essay, Jack Clark, a co-founder of Anthropic, points to research and concludes that AI systems are about to negate bioweapon non-proliferation because they can make bioweapons that evade DNA synthesis classifiers.

We’ve seen some of the most prominent AI scientists speaking out about AI technology because of the risks. MIT maintains The AI Risk Repository, “a comprehensive living database of over 1600 AI risks categorized by their cause and risk domain.”

There are so many reasons to disdain and fear AI, apart from copyright issues.

Licensing as a Solution

Within this miasma, the largest AI companies are approaching some “content providers” about licensing their stuff. They’re mostly interested in news and periodicals — AP, Condé Nast, The Financial Times, The New York Times, News Corp, Springer and The Atlantic are all on board. OpenAI made most of the deals, but so did Microsoft, Amazon, Perplexity and a few others.

Within this miasma, the largest AI companies are approaching some “content providers” about licensing their stuff. They’re mostly interested in news and periodicals — AP, Condé Nast, The Financial Times, The New York Times, News Corp, Springer and The Atlantic are all on board. OpenAI made most of the deals, but so did Microsoft, Amazon, Perplexity and a few others.

And then there’s the book publishers. Ithaka S+R provides the best tracking of the book publishing AI deals. At first blush you might think: well, that’s a whole bunch of activity. But pretty quickly your thoughts turn to: Is that all there is?

Wiley is well-represented on the list — they have been, by far, the most aggressive deal seeker. Taylor & Francis/Informa appears three times. And then things trail off: three university presses, one trade publisher… not much. Yes, AI deals always have a confidentiality component, so we’re missing the specifics and the amounts. But I think we at least hear about most of them.

Amidst all of the concerns that our industry faces with AI, is licensing content a solution?

Selling Your House For Firewood

Louis Waweru, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

You really must read Hamilton Nolan on the topic of licensing (from whom I’ve stolen this subhead). He’s a long-time journalist who writes about “power, how it is wielded, and how it can be channeled for the common good.” Nolan says that what the AI companies are doing now is “very much in line with the approach of many successful tech companies of the past, which is ‘just do what we want and pretend that laws don’t really apply to our technology because it’s new, and then get so big and rich that we’re able to sort of buy our way out of it on the back end.’”

This, he writes, was the approach that both Uber and Airbnb took, with great success. “The conceit that any new technology renders all preexisting laws and regulations inapplicable is a profitable one,” he notes.

Is this what authors and publishers are abetting?

The Limits of Licensing the News

The early content deals were in part hedges around the penalties that might result from the many lawsuits working their ways through the courts. (Currently 54 and growing.) The big AI companies could prove that they were willing to enter into at least some content licenses. The big content providers could signal that they in turn were willing to offer AI training licenses for their content: theft had been unnecessary. OK, point made. And then what?

There was also the thought that AI search results were going to have been able to reference current events. The LLMs were trained on text at least a year old: how to respond with today’s news from Washington? OpenAI’s strategy appears to have been to establish a base news content library — just the big content providers. Perplexity.ai has followed a similar approach.

But that strategy only takes you so far: you’ve licensed the New York Times, but not the Washington Post or the Wall Street Journal. Will your AI engine answer queries referencing solely a single source, or a small selection of sources? That doesn’t make sense. Google Search links to everything (or, most everything) — that’s the standard expected from search. AI poses as omniscient. A small source library won’t cut it.

But that’s where they currently find themselves. When I ask ChatGPT what’s going on in Washington today, it offers responses from Time magazine, Politico and The Guardian. I ask it what the New York Times reported from Washington and the response is, “I can’t open NYTimes.com directly— their site blocks my browser.” (The Times is loudly suing OpenAI for copyright infringement, but signed a $20 million/year AI licensing deal with Amazon. Principles seem to be able to take you only so far.)

Google’s Gemini is similarly hamstrung, eventually admitting “As an AI, I cannot personally access websites that are behind a paywall, like The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal, because I do not have a financial account to purchase a subscription.”

If I go over to Google Search and ask what the Times or the Wall Street Journal reported today I get a quick AI summary and links.

I hadn’t realized this limitation until working on this post. I’m taken aback. I had thought that the AI engines had found a way to at least pull summaries from the open web. But apparently not. Bravo to the news media! Respect existence or expect resistance. They have managed to put limits in place that stop the AI engines from being everything answer engines. I’ll talk more about this limitation below.

Two Kinds of Training

Rags

Here comes a gross oversimplification, which would horrify the experts, but which is usable for our purposes. AI training comes in two flavors: broad language training for large language models, and then fact-retrieval, using what is inelegantly called, RAG, for Retrieval-Augmented Generation.

In the first instance you’re just training an AI to become conversational, in a sense to learn how to speak, to communicate. In the second instance you want it to also be specifically factual. This is where RAG emerges: give an LLM AI access to some very specific data, for very specific reasons, and you’ve got RAG.

There are reasons to think RAG is the future of licensing. More about that below.

Answer Engines and the Search for Perfect Information

Wikipedia explains ‘perfect information’ as “a concept in game theory and economics,” having nothing to do with the common meaning of those words. I think of perfect information as all of the relevant information available on a particular topic. If the topic is ‘economics’ it’s all but impossible to assemble perfect information on the topic.

Some 70,000 books have been published specifically on economics, alongside 2 million articles in more than 4,000 scholarly journals. (And then, of course, there’s a vast amount of video content, blogs, social media and more.)

AI LLMs haven’t accessed the bulk of that content, but they’ve got enough of it to be able to respond to even very detailed questions with very detailed answers.

Let’s then compare that to a very specific topic in economics.

There’s a concept called the “No-Trade Theorem,” coined by Paul Milgrom and Nancy Stokey in their 1982 paper “Information, trade and common knowledge.”

The paper has been cited 2,600 times, both in other journal articles and in books, a small fraction of the larger economics corpus. An LLM can easily ingest and process this amount of text. But most of those articles and books are behind paywalls, and cannot be accessed directly by today’s LLMs.

ChatGPT 5 estimates that to cover the whole “No-Trade Theorem” literature you’d need 30–40 licenses to be truly exhaustive (capturing books, long-tail book chapters, regional journals, and older conference volumes).

This is what I call “AI’s perfect information problem.”

On the one hand the AI industry predicts “AGI” — Artificial General Intelligence — with “the cognitive abilities of a human, allowing it to understand, learn, and apply knowledge across a wide range of tasks and domains.” But AGI, apparently, does not presuppose omniscience. Is AGI just brains without, necessarily, knowledge?

This puts the licensing conundrum into focus. How much information do you need to encompass to claim to appear smart? Not, necessarily, a heckuva lot. But how much information do you need to be truly authoritative? All of it.

Patrik the yugoslavian engine, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Obviously this doesn’t matter if the topic at hand is the best recipe for guacamole, or understanding the decline and fall of the Roman empire. It matters a lot if you want to track and understand the current research on Parkinson’s disease, or to decide on the most resilient building materials to use for high rise construction on earthquake fault lines. AGI cannot be relied on if it can’t access the latest knowledge.

According to a 2022 journal article by Michael Gusenbauer, authoritative data can be contained within one or more of up to 56 different bibliographic databases. Will it be necessary for omniscient AI to have access to all 56?

How Important are Books as Information Sources?

In the supplementary material to an often-cited paper, The World’s Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information, Martin Hilbert and Priscila López drill down on how much information is stored in books. According to my own analysis of their findings, books hold less than 0.01% of world’s information. I sought to update that analysis for this post and asked Google Gemini “what percentage of the world’s information is held in books, both print and digital?” It conclusion was that “the book corpus is quantitatively negligible” within the information ecosystem in the current era, that “the volume of the world’s information contained in books, inclusive of both print stock and digital formats, is mathematically marginal in the contemporary information ecosystem.”

It also highlighted that the “minimal volumetric presence of books should not be confused with intellectual insignificance (emphasis mine).”

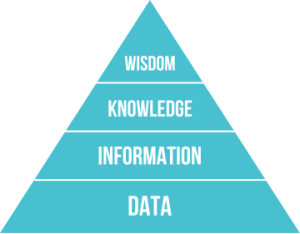

The DIKW pyramid

Longlivetheux, CC BY-SA 4.0

The DIKW pyramid, first proposed in 2007, is a simple model of how mankind gains wisdom. Wikipedia has a long entry on the topic, too long. Here’s a shorter explanation from Datacamp. I’ll quote from their definitions:

- Data refers to raw, unprocessed facts and figures without context.

- Information is organized, structured, and contextualized data.

- Knowledge is the result of analyzing and interpreting information to uncover patterns, trends, and relationships.

- Wisdom is the ability to make well-informed decisions and take effective action based on understanding of the underlying knowledge.

In terms of publishing, think of the pyramid in connection to nonfiction books, and perhaps scholarly journal articles.

The text of the book or journal article mostly resides at the top two rungs of the pyramid. Good useful knowledge is shared in many books and articles, derived from information and data the author has studied. In the very best books and articles (a small percentage of the total published), the author(s) have developed wisdom from their knowledge, and have found a way to express the wisdom through words.

AI based in large language models is not itself wise. It may be able to parrot some wisdom contained in its training set, but, in current iterations, cannot develop or properly emulate wisdom.

What AI is very good at is knowledge: “the result of analyzing and interpreting information to uncover patterns, trends, and relationships.” That’s AI LLM’s not-so-secret power.

AI also excels at information processing: organizing, structuring, and contextualizing data.

A fundamental mistake that publishers are making is imagining that the information and knowledge contained within the books they publish has more value to advanced LLMs than does the data that underlies all of the interpretations and conclusions reached by often-expert, but oh-so-human authors.

AI systems could today regenerate the content of most of the nonfiction books and scholarly articles ever published, all but the best. To do so it would need access to the information and data that underlies the knowledge expressed in each work. Where data is unavailable, it can process the published information on each topic (which, often, is all the author relied upon as well).

AI, then, also has the ability to generate the content of some very good new nonfiction books and journal articles, which have never been published. Its verbal acuity is still a work in progress, but AI is definitely able to build knowledge.

Still, to get access to authoritative data and information, the AI companies will need licenses. Lots of licenses. Some AI companies are starting to come to recognize this. Many more will.

The Anthropic Agreement

I want to stay as far away from discussing legalities as I possibly can, but I can’t sidestep the recent class settlement that Anthropic made with book authors. The settlement itself wasn’t about AI issues, such as fair use, per se. It was about digital book piracy. But it managed to set a possible base price for theft — $3,000 per book. Seems like a lot — $1.5 billion overall, but for Anthropic, one of the largest AI companies, it was affordable.

I want to stay as far away from discussing legalities as I possibly can, but I can’t sidestep the recent class settlement that Anthropic made with book authors. The settlement itself wasn’t about AI issues, such as fair use, per se. It was about digital book piracy. But it managed to set a possible base price for theft — $3,000 per book. Seems like a lot — $1.5 billion overall, but for Anthropic, one of the largest AI companies, it was affordable.

More importantly, the judge made it more or less clear that Anthropic could have avoided the whole shemozzle if they’d simply purchased a used copy of each book, ripped off the cover, scanned the pages, and OCRed the text.

They could have bought most of the books, used, for $5 or so. 1DollarScan charges about $3 to scan a 250-page book. (Though, at scale, the price would be lower.) Then there’s OCR, clean-up, tagging and so on, all of which can be done overseas in lower-cost countries. Let’s stretch the cost to $25/book, all-in.

That would have been big savings for Anthropic. But it’s also a signal to other AI companies: You can legally create a training set of one million books for $25 million dollars. That should be appealing.

(Footnote: The judge in the Anthropic case also stated that, apart from the pirating, the actual LLM training was, in fact, fair use. Think of this as an early indicator of where these lawsuits may land, but not as a definitive outcome — many other lawsuits are winding through the courts. There’s an excellent new backgrounder on the case from Dave Hansen. Dave concludes: “Nobody really won in this suit.”)

AI Goes to Washington

As I reported in this blog a couple of months ago, authors and publishers cannot look to Washington for support either in copyright litigation or in licensing. President Donald Trump said explicitly, “Of course, you can’t copy or plagiarize an article. But, if you read an article and learn from it, we have to allow AI to use that pool of knowledge without going through the complexity of contract negotiations….”

It’s difficult to assess what specific impact that is having or might have on the future of licensing. It’s similarly difficult to imagine that it bodes well.

The Brokers

Into every crisis a little opportunity must come, and now there are over two dozen companies that propose to act as intermediaries between textual content owners and the AI companies, in various forms and capacities.

I’m not going to describe them all, but because I collect publishing startups, I’ll share my list: Amlet, Avail, Bookwire, Cashmere, Copyright Clearance Center (CCC), Created by Humans, Credtent, Data Licensing Alliance, Dataset Providers Alliance, Defined, Factiva, Human Native, LivingAssets, Poseidon, Profound, ProRata, Protégé, Really Simple Licensing, Redpine, Research Solutions, ScalePost, SmarterLicense, Spawning, Sphere, Story, Synovient, Tollbit, Trainspot, Valyu and Wiley. Phew! Thirty of them, each a little (or a lot) different in their approach. (Plus a slew of other services focused primarily on audio and/or video content.) All are hoping for some piece of the content licensing action.

I’m not going to describe them all, but because I collect publishing startups, I’ll share my list: Amlet, Avail, Bookwire, Cashmere, Copyright Clearance Center (CCC), Created by Humans, Credtent, Data Licensing Alliance, Dataset Providers Alliance, Defined, Factiva, Human Native, LivingAssets, Poseidon, Profound, ProRata, Protégé, Really Simple Licensing, Redpine, Research Solutions, ScalePost, SmarterLicense, Spawning, Sphere, Story, Synovient, Tollbit, Trainspot, Valyu and Wiley. Phew! Thirty of them, each a little (or a lot) different in their approach. (Plus a slew of other services focused primarily on audio and/or video content.) All are hoping for some piece of the content licensing action.

I’ve been talking to many of them, and they’re mostly serious and thoughtful about the challenges the publishing industry faces. But it’s early days, and the paths to content licensing remain uncertain.

How Much Licensing Revenue are We Talking About?

The publishing industry, understandably, has been approaching AI licensing in the context of traditional content licenses, seeking tightly defined use limits, term limits, and pricing models. The AI industry has, apparently, just been winging it, sometimes offering a pittance, and sometimes a chunk of cash (but nearly always with few usage restrictions). They’ve had a ‘take it or leave it’ upper hand which they’ve wielded with little concern for the sensibilities of publishers.

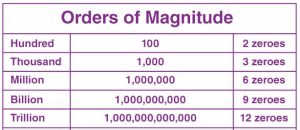

Source: BYJU’S

The training of large language models, as you’ve heard elsewhere, takes place on a grand scale, in terms of science, energy, and word count. Good ol’ GPT-3 was trained on half a trillion words. Meta’s Llama 3 was pretrained on 11 trillion words. Your 75,000-word book is smaller than a drop in the proverbial bucket.

The general sense in the publishing business is that licensing can run about $100/book, sometimes a little more, sometimes a little less. Stephen King gets the same stipend as Luna Filby. It’s not much for an individual author, but for the publisher it adds up quickly. Publishers seem to have settled mostly on a 50/50 revenue share, though the Authors Guild recommends roughly 25/75 favoring the author.

By all accounts, the HarperCollins book deal was an outlier. $5,000 per book! (With a 50/50 share to the author.) On the face of it, the licensee overpaid by a significant margin. (Who knows if there were other considerations that made this deal make sense.)

Some of the training deals are per word. I found only one published estimate of per word value — .001 cent, which would total $75 for an average 75,000 word book. But these prices are more often applied to bulk content (sometimes called “tonnage”!) from periodicals or the open web — articles, blog posts, social media, and so on. Either way, it’s a pittance in an industry that prices content by its inherent value, not the number of words.

(I tried to total the value of all of the text licensing deals announced to date and arrived at a number of $300 million. With so many deals not fully reported, I know that’s low. But it gives you a sense of scale — just a drop in the bucket of overall AI training costs.)

AI training is mostly based on the ‘bags of words’, where the content, per se, has little or no value (although the sentence structure and vocabulary often does).

With RAG the obverse is true: the content matters far more than the word count. It looks like RAG is where we’re headed, and that should be good news for most authors and publishers.

Licensing Contract Duration

Only a short note here: The contracts that I’ve heard described often mention 3-year terms. But if the license is for general training of a large language model, everyone knows that you can’t pull the stuff back out, arbitrarily, after 3 years. Once again, RAG suggests a different licensing model, where time limits could make sense.

A few of the licensing services are advocating for ‘per use’ pricing. That sounds to me like wishful thinking, except in some RAG instances. Who knows how this might evolve.

Does Licensing Make Content Visible?

One of the more interesting and more complex arguments that supports AI licensing is that of making published content visible in a world where the majority of user interactions with the machine are mediated by an LLM-based AI.

You can turn this one on its head and ask: if your content has not been licensed for AI training, is it invisible? The short answer is ‘yes’. Think of it in simpler terms. If a Google search can’t find your blog post/article/research/etc. is it visible? Technically perhaps yes, but in practical terms, simply, no. So too in the emerging world of AI interactions.

The fly in the ointment is attribution. Your content may be visible via AI search, but does anyone know it’s yours?

Attribution is at the heart of the RAG models of AI. Attribution adds value to researchers who want to delve more deeply than a search outcome. But the use case presupposes that the searcher is interested in the sources.

Still, I land on the side of visibility here. The precariousness of attribution can militate against licensing, but I see no upside to invisibility.

A Place at the Table

I’m trying to remember that era, early in my career, when text-based content publishing industries were king. I think I’ve now forgotten. It was certainly pre-internet.

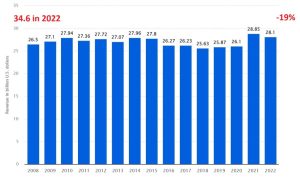

Tonight I revisited a survey I conducted for Seybold Seminars in the years 1999-2000. Among other things I noted a BISG report that stated that “consumers purchased fewer books in 1998 than they did the year prior… the first time that the industry posted a year-to-year decline in the demand for books.” Adjusted for inflation, the book publishing industry has been shrinking ever since. As have newspapers and other print-focused periodicals.

Tonight I revisited a survey I conducted for Seybold Seminars in the years 1999-2000. Among other things I noted a BISG report that stated that “consumers purchased fewer books in 1998 than they did the year prior… the first time that the industry posted a year-to-year decline in the demand for books.” Adjusted for inflation, the book publishing industry has been shrinking ever since. As have newspapers and other print-focused periodicals.

While other factors were at play, clearly the internet was a tipping point for traditional text-based content industries.

I see the publishing industries in an ongoing denial of the shift. But could AI be, in fact, a validation of traditional publishing? Unless we move into an entirely post-literate world, the careful reasoning and expression in long-form periodicals and books has no substitute: you cannot reconstitute Robert Caro’s The Power Broker from a YouTube video.

Beyond endless litigation, how can the publishing industries find common ground to push back against the AI companies? Right now publishers are ceding control. But there is a moment of opportunity while the litigation is still before the courts and licensing is still in flux.

The publishing industry is terrified of being judged for antitrust collusion (although they would have to choose between 5 identically-priced flights from 5 different airlines to get to Washington to testify at a hearing). Can we at least come together and decide, in broad terms, on recommended policies for licensing moving forward? If not that, can we at least launch a conference at which the topics are discussed?

Footnotes

* Later identified by Bloomberg as Microsoft.

** I’ve always felt that the malfeasance was mostly (though not solely) one of careless neglect by computer programmers, rather than a deliberate intention to break copyright laws. For example, The New York Times interviewed Suchir Balaji, a former researcher at OpenAI (who, very sadly, died soon after the interview, apparently by his own hand). Balaji said that they treated building out OpenAI like a research project. “‘With a research project, you can, generally speaking, train on any data,” Mr. Balaji said. ‘That was the mind-set at the time.’”