November 5th, 2025

Beware: This post talks about metadata for books, and it talks about ONIX, the data format used to convey metadata for the retailing of books. But it is also about technology in the age of AI.

It would be impossible to recap the whole story of metadata for books here, except in the clumsiest of fashions, and so if this is a topic that still mystifies, or that you disdain, move on. (Or, alternately, have a read of John Warren’s “Zen and the Art of Metadata Maintenance,” probably the best intro out there.)

A publisher literally cannot sell their books at retail, particularly online retail, without metadata, mostly expressed via ONIX. I mean literally, actually, totally. Publishers cannot upload a book for sale to Amazon without metadata. Amazon will not accept the upload. And so ONIX metadata is not a nice-to-have, it’s a must-have. Most publishing personnel don’t want to know about metadata at all — they leave it to the techies, or the marketing people. But it’s essential. Nonfiction books don’t have to have an index any more, and often don’t. But they do need ONIX metadata.

“Onix: It is a very aggressive Pokémon that will constantly attack humans”

What is this beast called ONIX? At its most rudimentary level, you can think of it as just a form that publishers fill out for new books. ONIX metadata includes the basics about a book: title, subtitle, author, publishers, pub date, retail price, ISBN, BISAC codes, and so on.

(Parenthetical: The ONIX standard is expertly maintained by EDItEUR, a UK-based membership organization, with participation from virtually the entire publishing industry worldwide.)

The first version of ONIX appeared in 2000. Version 2 was published in 2001, and revised in 2003. The latest major release, ONIX 3, was published in April 2009, sixteen years ago.

Here’s the debacle:

ONIX 2.1 was ‘sunsetted’ (i.e. no longer actively supported) by EDItEUR at the end of 2014, nearly 12 years ago — it has not been revised or improved since. This is not a slight on EDItEUR — why update an old format, when something new and improved is readily available? ONIX 3 is so much more robust than 2.1 ever was. A lot of information about a book can be communicated in ONIX 3 that could never be expressed in 2.1. Using the data contained in an ONIX 3 file, publishers can sell more books than they can using 2.1. And if you already know how to use 2.1, ONIX 3 is not technically difficult to implement.

BISG used to publish a sort of shame list showing who was supporting each version of ONIX. The last copy of the list I’ve got is a decade old. At the time only 40% of respondents were using ONIX 3. I know it’s a much higher adoption now. But still…

The ONIX Timeline

Last week the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) published a post, “Time to Act: The ONIX 3 Transition is Actually Here.” It’s written by Claire Holloway, the hard-working chairperson of BISG’s Metadata Committee. Claire is, as always, reasonable in her outlook and fully supportive of the publishing community. But the story she’s telling is, to me, chilling, in the way it reminds of ONIX’s slow journey across two-dozen years.

Apparently Amazon is finally going to ‘force’ the publishing industry to transition to ONIX 3 — it has set a deadline of March 2026 for a full conversion.

But Claire points out also that the transition to ONIX 3 “isn’t just a technical upgrade—it’s becoming a legal necessity. The European Accessibility Act (EAA) requires metadata about an ebook’s accessibility features to be provided and communicated throughout the supply chain for any ebook being sold in the EU.” (The prior versions of ONIX have no ability to express this information because it wasn’t a factor way back when.)

So, in 2026, will the U.S. book publishing industry finally fully embrace a sixteen-year-old version of a standard that can make their businesses more profitable? Particularly when EDItEUR continues to update and improve the standard (we’re actually at version 3.1.2 now).

We’ll see.

——————————————————

But this post is more fundamentally about how technology is adopted into the book publishing industry. I’m now looking at a different technology, far more powerful and profound than metadata enhancement. It can help publishers become more efficient and also to sell more books. AI’s potential impact is a hundred times more profound than moving from ONIX 2.1 to ONIX 3.

Yes, I’m very conscious of the reasons for disliking, no, even hating AI technology. I talk about these frequently, in my book, my presentations, and in my blog posts. But the universe isn’t waiting for the book publishing industry to forgive AI’s original sin, or to come to terms with the many threats posed by the technology.

Typically understated illustration, created by ChatGPT.

Last week Adobe released the top-line results of a survey over 16,000 “content creators” from around the world. Of course Adobe’s idea of a content creator is different from ours — Adobe discusses content “such as images, video, audio, and design.” But 76% of respondents report that AI has accelerated the growth of their business or follower base. 81% say AI helps them create content they otherwise couldn’t have made. 85% believe AI has positively impacted the creator economy.

Several weeks ago I shared an early look at an income survey commissioned by ALLi of the self-published author community. They added a few questions on AI use, and found that over 25% of reporting authors were using AI tools, and nearly 75% of those report that the technology is having either some, or a strong positive impact on their income or productivity.

A survey from Gotham Ghostwriters and Josh Bernoff, released yesterday, featured surprising top-line numbers, such as “a surprising 61% use AI tools.” But if you focus just on the book writer responses, the numbers were in the 25% range (23% of fiction writers reported daily use of AI tools), consistent with the ALLi survey numbers.

Meanwhile, book publishing, steeped in tradition and trade practices, remains as technology-averse as ever. A BISG survey from last summer revealed lots of dabbling with AI tools (45%), but less than a quarter said that they are incorporating AI into existing workflows.

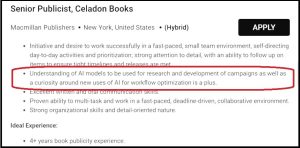

I went through the jobs classifieds on Publishers Marketplace and PW this morning and found nary a mention of AI skills. The marketing manager of one of the largest publishing imprints in the U.S. requires experience “in creating decks and presentations and presenting in front of large groups” but no proficiency with AI tools. The most demanding technical qualifications for an advertising associate at one of the Big 5 publishers is “Microsoft Excel, Word, PowerPoint, and Outlook.”

First time!

A senior publicist role at a Big 5 imprint requires… news flash: “Understanding of AI models to be used for research and development of campaigns as well as a curiosity around new uses of AI for workflow optimization is a plus.” That’s the first time I’ve seen AI mentioned in a publishing industry job post!

A couple of recent stats feature bleak vistas of the future of book publishing. After noting a 4.1% sales increase in 2024, the Association of American Publishers (AAP) reported sales in the publishing industry down 4.4% for the month of August, and down 2.8% year-to-date.

More troubling is the new study from the University of Florida and University College London, which found that daily reading for pleasure in the U.S. is “in free fall,” having declined by more than 40% over the last 20 years. Without readers, where is publishing?

——————————————————

As I was completing this draft I found a link to a just-published article by Ted Underwood about AI adoption in education, “AI is the Future. Higher Ed Should Shape It.” (Underwood shared a link to the article.) The article might be summed up as an invitation for educators to work with AI, not against it. AI is “a factor in education whether it finds a place in the curriculum or not.”

I’d invite you to read the article, swapping out ‘colleges and universities’ with “book publishers” and ‘education’ with “publishing.” You’ll end up with sentences that like this:

But adoption of AI in publishing has mostly not been driven by explicit partnerships between book publishers and AI companies. Rather, individual publishing staff have quietly started to use it in their work. To reject AI, publishers would have to prohibit staff from using it…. That sort of outright prohibition is so implausible that I’m not sure it’s worth debating….

If publishers want to stay at the forefront of knowledge production, we have no choice but to take responsibility for shaping AI and fitting it to our needs. If we don’t play that role, we will effectively cede intellectual leadership to the organizations that do.

Will the management of publishing companies figure out ways to harness the power of AI, while mitigating its drawbacks? There are some positive early indicators. But publishing’s historic discomfort with technology seems likely to block the industry from robustly integrating AI into current workflows. The implications are concerning.