March 30th, 2017

A few weeks ago AuthorEarnings released their latest book industry report. As always, there’s a lot of important information to grapple with—this time, even the title takes some wrangling: February 2017 Big, Bad, Wide & International Report: covering Amazon, Apple, B&N, and Kobo ebook sales in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The report is a shocker: it reveals that the traditional method of marketing books in other English language markets is obsolete, while at the same time the opportunity has never been bigger.

For those who haven’t discovered AuthorEarnings, it’s the only solid source of data on the self-publishing industry and more generally on the sale of ebooks (as well as online sales of print books). There are two other quantitative data sources serving the U.S. book publishing industry, the Association of American Publishers (AAP) and Nielsen BookScan. AAP provides net revenue figures for 1,200 of the largest U.S. publishers (and creates an annual estimate using additional data); Nielsen tracks book sales at retail.

There are problems with the AAP and Nielsen data. While AAP unquestionably captures sales at the largest publishers, no one knows how much they are missing. A 2005 study from BISG estimated that there are over 60,000 publishers in the U.S. The U.S. Census Bureau also misses many of these sales—its data represents only 2,663 “establishments”. The biggest problem with the Nielsen retail data is that it doesn’t include Amazon sales (because Amazon refuses to cooperate).

AuthorEarnings launched in early 2014, a cooperative effort of author Hugh Howey and a researcher known then (and still) only as Data Guy. They were determined to fill the gap by creating sales estimates from the major online retailers, including Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, Kobo and Google. While their methodology is transparent the industry was reluctant to accept their conclusions; their reports were still called controversial even last year. But the tide has since shifted and AuthorEarnings is now accepted as a key data source for anyone seeking to understand publishing trends in the U.S., and, as we see in their latest report, internationally as well.

Cliff Guren and I have been discussing the report. As we’ve done for several months now, we are posting an edited transcript of our conversation below. While we strongly recommend that you take the time to read the full report, there are a few key takeaways that we want to highlight and discuss in this post:

- The U.S. currently leads the world in both ebook penetration rate and the indie share of the ebook market, but other countries are starting to catch up: in particular the other four major English-language ones (New Zealand adds another small percentage). Taken together, ebook sales in these four additional markets add a combined 25% to the U.S.-only total.

- Self-published indie authors are taking far greater advantage of international sales than traditionally-published authors are.

- Bestselling U.S. indie authors are more likely to also be bestsellers in the U.K. than their bestselling traditionally-published U.S. counterparts. The same holds true in the opposite direction.

- Other than the top 1% of authors who receive coordinated international releases and global marketing campaigns for their titles, most traditionally-published authors are lucky to become bestsellers in a single market only, if ever at all.

- Traditionally-published genre authors, in particular, appear to be losing out on international ebook sales.

- Authors in English-language markets outside the U.S. have the greatest international opportunity: the enormous U.S. market. Traditional publishers in those markets succeed in selling U.S. rights for only their top titles; the bulk of their lists languish abroad.

Cliff: We have to start by thanking Data Guy at Author Earnings. He’s shining a bright light in an otherwise dark corner… Our industry has basing business decisions on bad data. For example, in February the AAP reported that trade sales were down 1.6% for the first three quarters of 2016. They also reported that ebook sales were down 18%. Data Guy’s January DBW Presentation “Print vs. Digital, Traditional vs.Non-Traditional, Bookstore vs. Online: 2016 Trade Publishing By the Numbers” shows that print trade sales for 2016 were up 3.3% and ebook sales were up 4% (albeit for the whole year). Why the discrepancy? As the latest AuthorEarnings report demonstrates, it’s impossible to understand what’s going on in the industry without including all of Amazon’s data, most prominently self-publishing and Amazon imprint sales.

What follows below is a snapshot of where the book industry stands today. Each of these assertions is backed up by the data in this latest AuthorEarnings report.

• The U.S. market share of the Big Five is shrinking.

• Ebook revenues (as a percentage of the total dollars spent of books as a category) are still growing (though more slowly).

• Amazon dominates ebook sales—traditional and self-published combined—with nearly 80% of the market in the U.S. and more than an 80% share in the U.K.

• Apple is the next largest ebook retailer, but with a mere 9% in the US and about 7% in the U.K.—no one else has any meaningful share in the two current largest English-language markets.

• Amazon is the dominant retailer for indie and self-published content, and Amazon’s own imprints are growing rapidly—accounting for 14% of ebook sales in the Amazon bookstore (up 4% from the January, 2016 report). If the past is any predictor, the share of the Big Five outside of the US will continue to shrink as Amazon’s self/indie publishing platforms grow and as Amazon expands its branded publishing program.

What’s your take on the report?

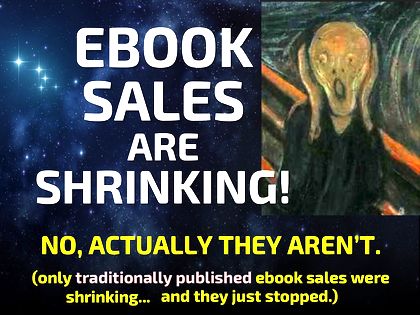

Thad: Several issues emerge from the data. First, people need to throw out, once and for all, any belief that ebook sales have fallen from their peaks in the last couple of years. The claim in repeated once again in a recent Guardian article, which led to the usual triumphalist chorus of comments and tweets affirming that the printed past remains largely in place.

The ebook claim is exclusively true for the larger traditional publishing companies reporting into the AAP and Nielsen. And, it’s almost certainly true that the reason for this shift is the insistence of these publishers to keep ebook pricing up over $9.99, often much higher, and often higher than the cost of a discounted new print book. Consumer surveys record that anything over $9.99 is a significant barrier for the average book buyer (and moreso for genre fiction readers).

But also implicit in this discussion is that if a customer won’t buy a $14.99 ebook, they will instead buy the same hardcover for $13.99 or so. But what if the result is that won’t buy either version?

Cliff: The battle isn’t print vs. digital—it’s reading for pleasure vs. all the other forms of entertainment that now compete for our attention at home and on our mobile devices. That said, the indie presses and self-published authors seem to be doing a better job of targeting the micro-communities that are willing to pay for books. What’s in store for the Big Five?

Thad: This same Author Earnings report includes the assertion that the “Big Five ebook market share has fallen precipitously in early 2017, to just 20.8%.” This was reinforced just this week when Bertelsmann, parent to Penguin Random House (PRH), announced a 9.6% drop in revenue and 3.6% in profitability (EBITDA).

We don’t need to feel sorry for those big companies. They are all part of larger conglomerates which are mostly still profitable. For example, PRH’s parent, Bertelsmann, reported that despite the gloomy news at PRH, overall profit rose 3.3% because of success in its TV, music and services divisions.

It’s the authors I’m concerned about. In the face of solid data about strategies that would almost certainly increase an author’s sales, the larger publishers have been following practices that lower them. They are inadvertently undermining their authors prospects not only in their home markets, but also abroad.

The time-honored method for selling American English-language titles abroad is selling publishing rights into other markets. This made sense in a world of print books: the logistics of international distribution were tough for all but the largest publishers. So copyrights were resold (licensed) instead of printed books. For English-language, this meant mainly the U.K. (Canada is mainly a re-distribution territory of the U.S. or the U.K.; Australia is almost always a distribution territory for U.K. publishers.)

The time-honored method for selling American English-language titles abroad is selling publishing rights into other markets. This made sense in a world of print books: the logistics of international distribution were tough for all but the largest publishers. So copyrights were resold (licensed) instead of printed books. For English-language, this meant mainly the U.K. (Canada is mainly a re-distribution territory of the U.S. or the U.K.; Australia is almost always a distribution territory for U.K. publishers.)

As Data Guy acknowledges, this works just fine for the top 1%. But below that? It’s a crapshoot. At the midlist and below the publisher will often fail to sell rights. In the market between the top 1% and the midlist, rights will often be sold, but there’s not much cash involved and hence not much commitment from the buyer: the book is ghettoed to an also-ran status even before it’s published.

If the publisher fails altogether to sell rights to a particular book, the default assumption is “oh, there wasn’t much international interest in that title,” when it should be: “those fools in the U.K. are missing the boat on this one and we’re going to market the heck out of it on Amazon, Apple and Kobo’s international stores.”

As noted above, the result is “most traditionally published authors are lucky to become best sellers in a single market only, if ever at all.” The traditional rights sales system essentially fobs off the global responsibilities of the U.S.-based publisher. The result is that they become very U.S.-centric in their marketing and promotion: they’re not thinking of global sales opportunities because they’re not handling global sales. Those are shifted onto the “rights department.”

Independent authors, on the other hand, increasingly appreciate the trends that AuthorEarnings reports: as noted above, self-published authors can increase their sales by some 25% just by paying attention to other English-speaking countries. That’s huge.

Cliff: Data Guy’s January DBW presentation sharpens your point… Traditional publishing is now the narrow, rocky path for most authors with books in categories such as romance and thrillers where readers have overwhelming moved to ebooks and self-published content has gained the most traction. In 2016, 156 million romance titles were sold online, and 96% of those sales were ebooks.

• 55% were self-published or published under a single-author indie imprint

• 11% were Amazon imprints

• 34% were from traditional publishers

Data Guy’s numbers show that Amazon has 82% of the English language ebook sales in the major English-language markets. If you’re a romance author you can safely say that Amazon is your best bet for reaching your readers around the world. They are reading ebooks and they are buying them from Amazon. Sci-fi (adult and juvenile), fantasy, horror, action/adventure and mystery are following the same pattern. Adult general fiction isn’t far behind.

In summary: For self-published authors the news is very good. But an overriding challenge remains: too many books are being published, and ebooks don’t go out of print.

2017 should be declared “International Self Publishing Year”—self published authors need to include every English-language country in their core market focus. How best to do so is the topic for another blog entry.