September 21st, 2016

The Bestseller Code is already the most talked about insider’s book on the writing and publishing industry. Who wouldn’t want to know if a computer can predict whether a manuscript will be a bestseller? What author wouldn’t want to know if there’s a scientific formula for plotting and writing novels that will propel them onto the New York Times bestseller list?

I don’t have to do any computational analysis to predict that The Bestseller Code will itself be a top bestseller. It’s provocative and it’s profane: the book challenges many of our assumptions about how writing and publishing work. It embraces a complex scientific methodology and makes it (almost) fun and (almost) comprehensible. The co-authors, Jodie Archer & Matthew L. Jockers, both PhDs, keep things rolling along: the text is bright and lively.

I don’t have to do any computational analysis to predict that The Bestseller Code will itself be a top bestseller. It’s provocative and it’s profane: the book challenges many of our assumptions about how writing and publishing work. It embraces a complex scientific methodology and makes it (almost) fun and (almost) comprehensible. The co-authors, Jodie Archer & Matthew L. Jockers, both PhDs, keep things rolling along: the text is bright and lively.

But what interests me most is whether The Bestseller Code delivers on its promises. That matters, given what’s at stake. If indeed they’ve uncovered the answer to the biggest secret in publishing — what, exactly, makes a book a bestseller — that’s a game-changer, and we need to know.

On the other hand if I had discovered the holy grail of publishing would I sell it for $25.99 a copy? Better perhaps to over-promise and under-deliver and save the precise ingredients for a wealthier patron. But how to skirt that fine line…

Well, you ask, what do the Archer & Jockers promise? The authors, I’m reluctant to say, seem like a couple of slippery fish. It proved a challenge to pin down their claims.

Promises, Promises

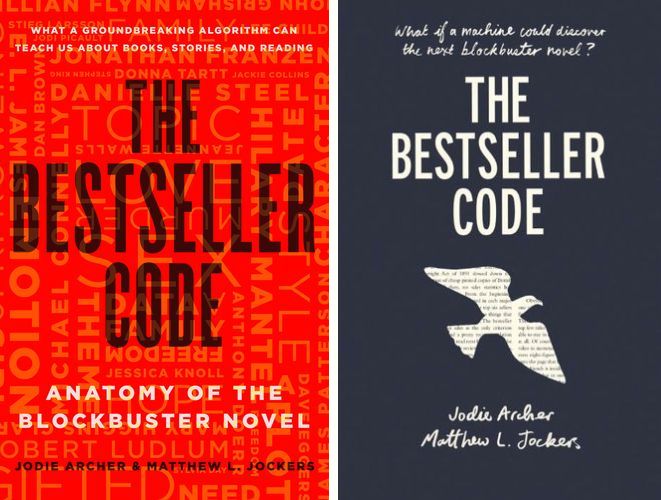

The front cover of the book is muted in its hyperbole. The title implies but doesn’t declare. The subtitle states that the book uncovers the “anatomy” of “blockbuster novels” while the top blurb refers to “a groundbreaking algorithm” that can teach us about books and reading. The U.K. cover just asks rhetorically “What if a machine could uncover the next blockbuster novel?”

The inside flap of the U.S. edition poses the question “what if there were an algorithm that could predict mega-bestsellers with stunning accuracy? What if it knew, just from reading an unpublished manuscript, (if it) would sell in huge numbers, but also (if it) had signs of New York Times bestselling all over their pages?” Well, what if? “Thanks to (the authors), the algorithm exists, the code has been cracked, and the results are stunning.”

The code is named by the authors the “bestseller-ometer” and it “makes predictions, with fascinating detail, about which specific combinations of (themes, plot, character, setting) will resonate with readers. Somehow, in all genres, it is right over eighty percent of the time.”

Do I sense a little pull-back in that last paragraph? The code makes predictions, but now the predictions are not of bestsellerdom, per se, but rather of what “will resonate with readers.” The rest of the flap copy is muted in its claims: the book “offers a new theory,” “reveals the most important theme in bestselling fiction and which topics just won’t sell,” and so on.

Do I sense a little pull-back in that last paragraph? The code makes predictions, but now the predictions are not of bestsellerdom, per se, but rather of what “will resonate with readers.” The rest of the flap copy is muted in its claims: the book “offers a new theory,” “reveals the most important theme in bestselling fiction and which topics just won’t sell,” and so on.

The inside flap of the U.K. edition is more modest, just that mega-hits can be “explained and identified” and the book “explores the hidden patterns at work in the biggest hits.”

Let’s delve into the text.

“Corpus” is an important term for understanding the claims of The Bestseller Code. (In fact “corpus” appears 23 times in the book. I counted. Using some software. Microsoft Word.)

Corpus just means a collection of books. Any designated collection. The scope of the collection assembled by the authors of The Bestseller Code is itself a little tough to pin down. Most of the articles about the book refer to a corpus of 20,000 volumes (one reviewer decided it was 25,000). And indeed the co-author, Jodie Archer, did conduct a study of 20,000 novels (“published before 2010”). The study formed the basis of Archer’s 2014 PhD thesis Reading the Bestseller: An Analysis of 20,000 Novels, which in turn led to landing a publisher for this book, which advanced “six figures, at auction”).

But for the current volume the authors “built an entirely new collection that was both more diverse and more current.” It’s a corpus of “just under 5,000 books, and they include a diverse mixture of non-bestselling ebooks and traditional published novels, and just over 500 NYT bestsellers.”

And so this 5,000 book corpus provided the raw text for the two doctors to conduct their experiments.

Chapter one sets the stage. “The bold claim of this book is that the novels that hit the New York Times bestseller lists are not random, and the market is not in fact as unknowable as others suggest.” Our “algorithms allow us to discover new and even as yet unpublished books with similar hallmarks of bestselling DNA… we discovered that there are fascinating patterns inherent to the books that are most likely to succeed in the market… [You’ll learn] how [our model] discovered that eighty to ninety percent of the time the bestsellers in our research corpus were easy to spot. Eighty percent of New York Times bestsellers of the past thirty years were identified by our machines as likely to chart.”

Hmm. They’re not claiming here that we, the humble reader, will learn how to create or spot bestsellers, only that they have. Yet it’s not some random slush-pile manuscripts they’ve zeroed in on. The corpus consists of already published books. Still the code they’ve developed is what would be used for slush-pile analysis: “every book was treated as if it were a fresh, unseen manuscript.” Each book was rated not just broadly as to whether it would land on the list but more precisely “with a score indicating its likelihood of being a bestseller”. This is precision work.

From here the claims seem to expand. Their method, we’re told, “could just change publishing” and can “even prove a long-held industry theory wrong [that selecting which books to publish is an educated guess] and make bestselling predictable.” Then “consider the question that started our research. Can bestsellers be predicted?” The answer, they explain at length, is yes.

And the authors tell us why this is so important. Remember, they write, “that the bestseller rate in the industry as it stands is less than one-half of one percent. That’s a lot of gambling before a big win.” Indeed.

So do Archer & Jockers give us the formula to substitute science for a game of chance? No, they don’t. They describe it in considerable detail over the book’s six chapters (plus epilogue plus postscript). But the source code is not to be found. Nor, for that matter, the names of the 5,000 books used to hone the code. I asked the authors if they intend “to sell or license the code to publishers and/or authors?” The response: “No concrete plans at the moment.” (In 2000 Jockers launched a business called Authors A.I., aimed primarily at authors, not publishers.)

What About the Code for Authors?

If Archer & Jockers won’t tell publishers exactly how to detect a bestseller in a slush pile do they at least tell authors how to write to avoid the slush pile?

I think that they do. The bulk of the book concerns the authors’ analysis of theme, plot, style and character in novels. They combine a traditional dissection of what works and what doesn’t with their own secret sauce. Examining the work of Danielle Steel and John Grisham they determine that these hugely successful authors devote a third of their most successful books to singular themes, the legal system for Grisham and domestic life for Steel. They continue:

It turns out that successful authors consistently give that sweet spot of 30 percent to just one or two topics, whereas non-bestselling writers try to squeeze in more ideas. To reach a third of the book, a lesser-selling author uses at least three and often more topics. To get to 40 percent of the average novel, a bestseller uses only four topics. A non-bestseller, on average, uses six…

That sounds prescriptive to me. Later in the chapter (on themes) they are even more specific:

Among the good, the popular, and (for writers) the go-for-its [themes]: marriage, death, taxes (yes, really). Also technologies—preferably modern and vaguely threatening technologies—funerals, guns, doctors, work, schools, presidents, newspapers, kids, moms, and the media. By contrast, among the bad and unpopular, we already have sex, drugs, and rock and roll. To that add seduction, making love, the body described in any terms other than in pain or at a crime scene. (These latter two bodily experiences, readers seem to quite enjoy.) No also to cigarettes and alcohol, the gods, big emotions like passionate love and desperate grief, revolutions, wheeling and dealing, existential or philosophical sojourns, dinner parties, playing cards, very dressed up women, and dancing.

And on the next page:

And, when it comes to that one, big, perennially important question, the readers are clear in their preference for dogs and not cats.

Got it. Sounds like a plan.

But for writers of fiction Archer & Jockers are specific about what they can’t help with:

We are not going to claim that reading this book for the first or even second time is going to turn you into a bestselling fiction writer. This is not a prescriptive “how to” book and comes attached to no guarantee… part of the beauty of this story is the twist it gives to the old axiom that great writing is a skill that can’t be taught…

…it will not give you a formula to apply. This book will tell you a lot about blockbuster DNA, but you won’t be able to copy it any more than you can slice off Adam Johnson’s fingerprints and type with them on your own hands.

Our belief, while it may be irritating and old-fashioned, is still that if you want to be a bestselling writer then first you have to learn and really appreciate fiction with as many tools as you can… But please don’t complain that you looked for an easy formula to get a million-dollar contract, and we didn’t give it to you. Anyone who offers you that is the same person who will offer you overnight weight loss if only you buy their magic tea.

How odd. The Bestseller Code won’t tell editors precisely how to identify bestsellers while implying that it would. But it does tell authors how to shape their prose and plotting just like bestselling authors, while making it clear that it doesn’t offer a formula for bestselling success.

As I write this tonight The Bestseller Code has hit #3,963 overall in books on Amazon.com. Let’s see if Drs. Archer & Jockers have created the code to reach #1.

October 21: As of today my bestseller prediction for The Bestseller Code has been misguided. It’s #35,206 in ebooks on Amazon.com and #27,722 in print books. And dropping. It hasn’t appeared on the New York Times bestseller list nor on the Publishers Weekly list. It’s receiving wide review coverage, but the reviews are tepid, generally dismissive of the book’s claims (The New Yorker: “The Bestseller Code Tells Us What We Already Know”). I imagined there would be much more controversy. So much for my prediction.