January 27th, 2016

“Reading comprehension,” Wikipedia tells us “is the ability to read text, process it and understand its meaning” (emphasis mine). I remember in Grade 5 at St. Anselm’s School when Mrs. Webber introduced our class to SRA cards, a ground-breaking reading comprehension game that help teach kids that reading wasn’t just mouthing the words and stringing the words together in sentences, something beyond “Dick and Jane Jump and Run.”

Computers, in turns out, can be useful tools to help us understand texts, particularly long texts. They can’t read a book and tell you exactly what it means, but they can tell you a heckuva a lot of other things about the work.

For this analysis I’m using the compiled 33 entries from Those Magnificent Manifestos. Let’s see what we can find.

• The number of characters? Dead easy to find just from one of Microsoft Word’s several text analysis features:

• The number of words? Microsoft Word counts those too:

![]()

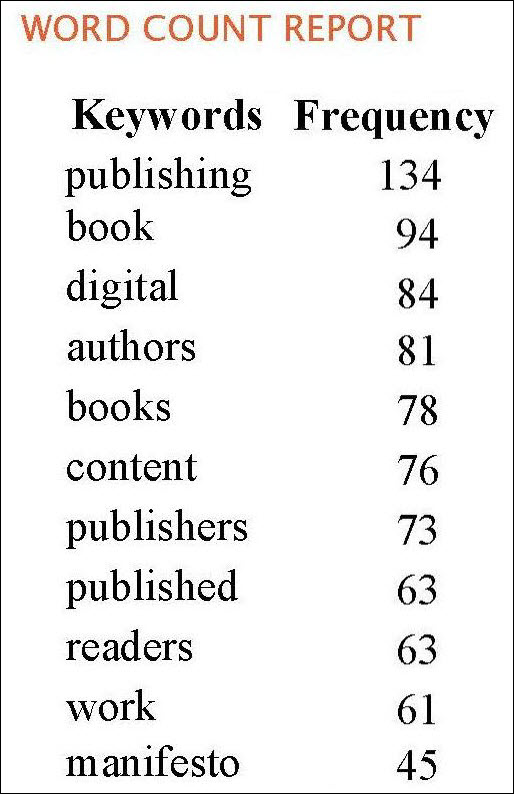

There are a lot of available tools that can perform the simple calculation of how often each word appears in the document.

Here I’m using “Online Word Counter” from TextFixer.

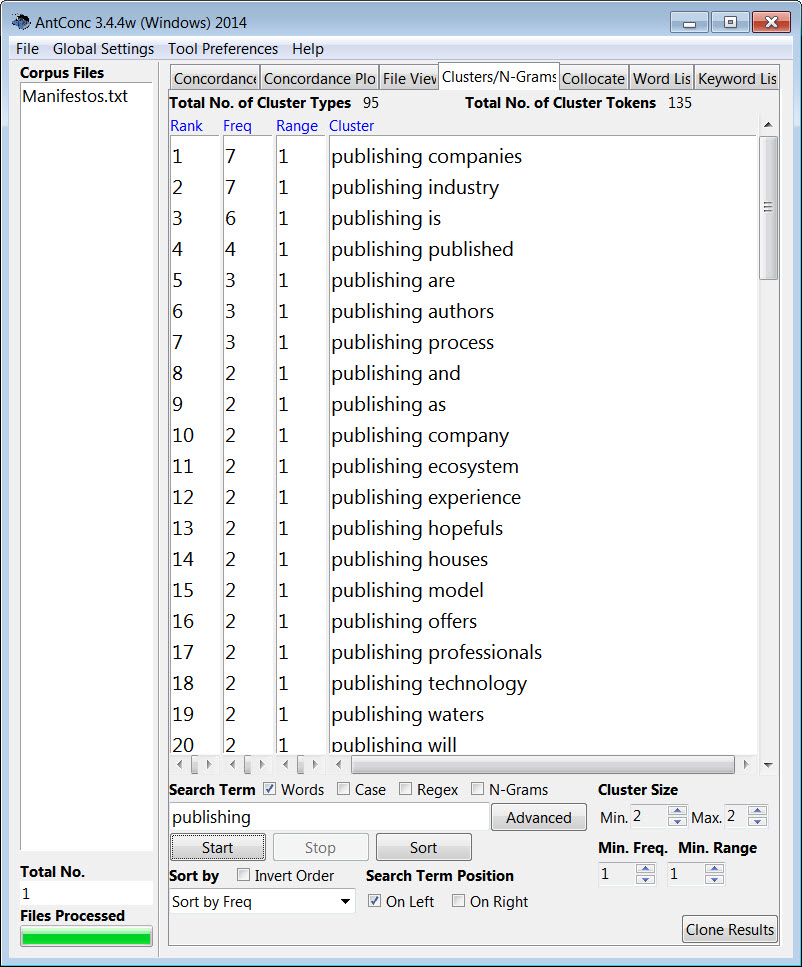

I guess we’re not too surprised that “publishing” is by far the most-often used word in Those Magnificent Manifestos. But I got curious about context. An N-Gram viewer shows me the 2-word phrasing used with the single word “publishing”.

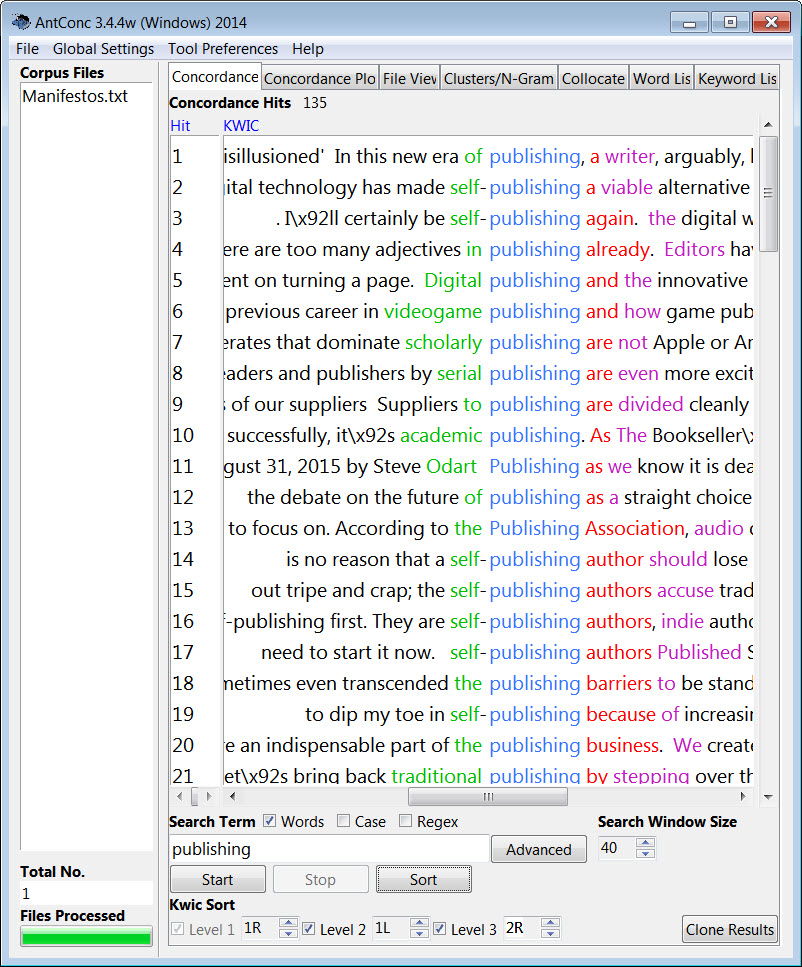

…While a concordance reveals the broader context where the word appears (which can also help in the preparation of an index):

• Knowing which words (of the words that matter) appear most frequently in the text I can use the TAPoRware Summarizer to help me focus on the sentences that contain two or more of these high frequency words. Here’s a sample from the results:

Digital technology has made self-publishing a viable alternative to the traditional system, and it’s not just for those who can’t find a publisher.

I’m one of an increasing number of authors who have abandoned the submission treadmill in favour of the freedom of producing our own books.

Recognise that authors are an indispensable part of the publishing business.

Publishing one of our books shouldn’t give you the right to control the rest of our careers.

Digital production means books never go out of print so rights never revert.

Its 25 years since my first book was published and, in that time, I’ve seen the author/publisher relationship become more and more tilted in the publishers’ favour.

Now digital technology has put power back in the author’s hands, that relationship needs to become more balanced.

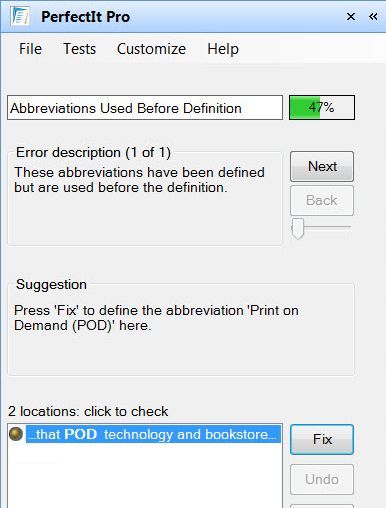

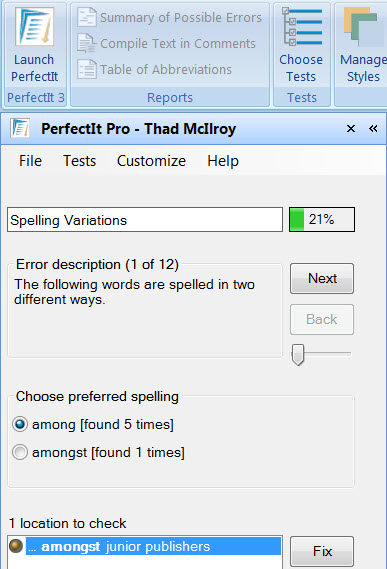

There are also tools that can take a text and improve it with automated “editing” analysis. I’ve got a nifty Microsoft Word plug-in called PerfectIt that looks for inconsistencies within a document, such as words spelled different ways. Looks like “amongst” was used once, while “among” was the more common usage:

• PerfectIt also notice that when “POD” is first used it’s not defined as “print on demand”. Some readers won’t recognize the abbreviation so that should be fixed.

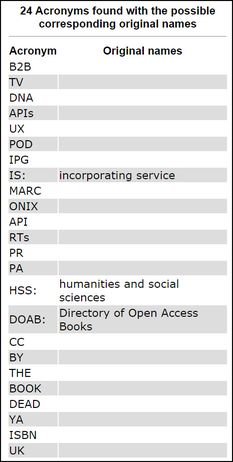

• TAPoRware Acronym Finder (overzealously) spots the abbreviations/acronyms all at once and tries to figure out what they stand for:

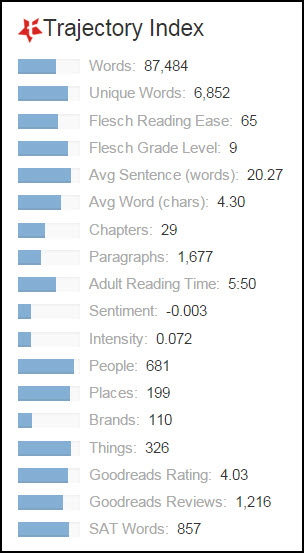

The market leader and eminent explorer of text analysis for trade publishers is Trajectory. Here’s a sample Trajectory Index:

At the same link you’ll see Trajectory’s Interesting Facts and Data Visualizations which takes the analysis further to capture nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and much more.

Some of these analyses are little more than cheap card tricks: Why would a publisher care how many paragraphs are in a book or the average number of characters in each word?

But what about the products (brands) mentioned in the text? These could be useful as metadata or in promoting the book. So too the people and places. Trajectory is onto something here.

So how to summarize the state of the art in text analysis? It’s becoming increasingly sophisticated as scientists in the fields of data mining, machine learning, natural language processing and information retrieval move it forward. It offers different value to authors, to editors and to publishers; and increasingly so.

It’s deeply embedded in the future of publishing.

Some Sites of Interest:

.txtLAB, a digital humanities laboratory at McGill University directed by Andrew Piper. “We explore the use of computational and quantitative approaches towards understanding literary and cultural phenomena in both the past and present.”

The Stone and the Shell: Using large digital libraries to advance literary history.

TAPoR: TAPoR is a gateway to the tools used in sophisticated text analysis and retrieval.