March 4th, 2015

The subject of the book publishing supply chain has been with us since IT enabled the recording of supply chain metrics. This allowed managers to plan process improvements based on solid data, not just seat-of-the-pant suppositions. As the results came in the publishing industry soon learned that it was not winning the supply chain battle. Back in 1998 a KPMG report (ppt) on the U.K. book publishing industry supply chain notes that publishing “is more costly and wasteful than other consumer goods sectors. Publishers’ logistics costs are 13% of sales, amongst the highest in industry (average costs to a typical consumer goods manufacturer are 6%).”

I think that we are entering an exciting new era in supply chain management and process improvement. There are two reasons for this. On the physical side, “total inventory management” programs reverse the equation. Instead of a publisher bearing responsibility for the efficiency of its supply chain processes, specialized distribution vendors step in and take responsibility for the chain. Their dedicated efficiencies provide them with costs low enough to be able to share the excess with publishing partners.

The second reason is digital. Most publishers continue to treat their digital production, distribution and marketing as something related to print, but standing just a little behind it, a bastard child trying to climb into the playpen. I think that the integration of digital with print offers publishers the big hit on solving the supply chain problem. It’s a complex rewiring of current workflows, but the rewards are worth the effort.

I’m going to spell out some of these ideas in a series of blog entries. My plan is to later write a report directed to all publishers, particularly smaller ones, showing them how to take advantage of the changes in supply chain technology and processes.

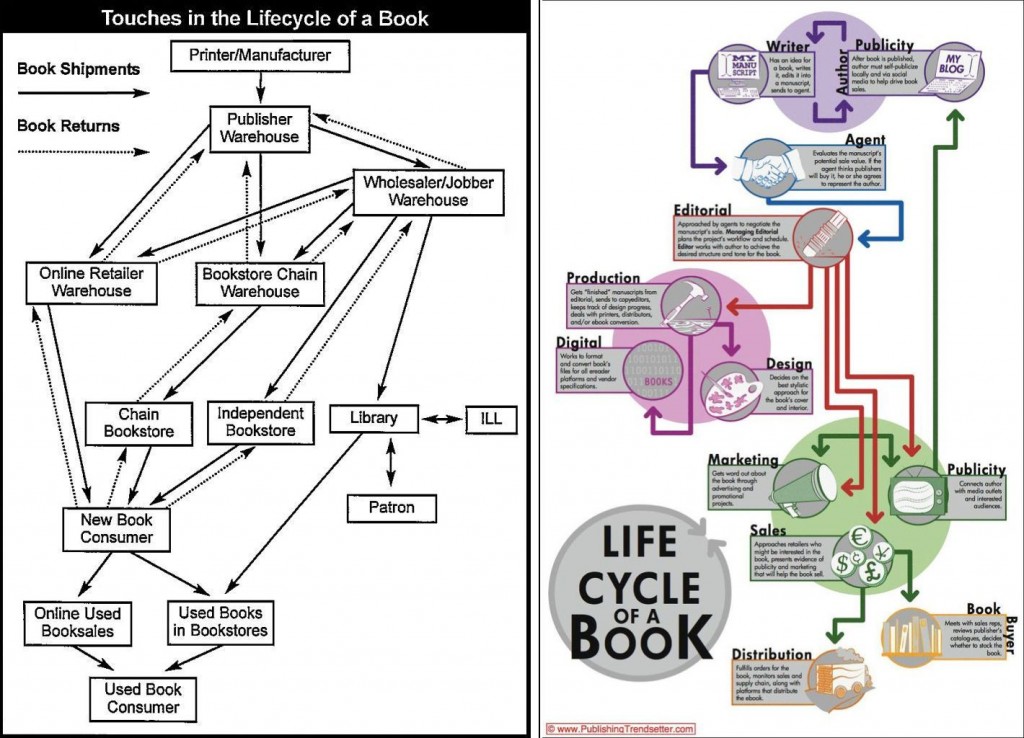

Let’s start with two diagrams that fill the page, courtesy of publishingtrendsetter.com, a great early (i.e. 2007) chart, and something a little more modern.

The chart on the left is focused mostly on the manufacturing and distribution aspects of the supply chain, while the chart on the right is “holistic” by including actual writers, agents, editors, designers and the whole marketing and publicity machine. As a result it’s more unidirectional than the first chart which captures the problem of returnability of printed books.

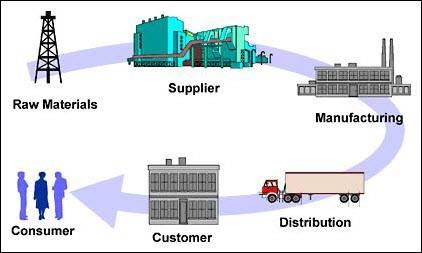

Indeed the notion of supply chain should start out with a very simple concept, moving raw materials through to processing (manufacturing), distribution and then on to the customer.

Wikipedia has a long entry on Supply Chain, with 32 footnotes. Investopedia brings it down to basics: “The supply chain encompasses the steps it takes to get a good or service from the supplier to the customer. (Italics mine.)

The key points are in those italics: (i) the supply chain concerns goods or services, and then (ii) moving those goods or services from a supplier to a defined customer, i.e. moving books to readers.

Problems in the Publishing Supply Chain

The publishing industry’s supply chain has never been a model that other industries have tried to emulate. As noted above, the publishing industry has had a long-term struggle with supply chain issues.

The publishing supply chain for printed books has always been plagued by two key problems:

(1) The cost of book printing, and deciding the number of copies to print.

(2) Physically moving books from the printer to the publisher’s warehouse (and/or distributor’s warehouse), to the distribution points, chain and independent booksellers and online resellers.

It sounds simple but complexity soon layers the challenges. For example:

(a) Publishers traditionally work with multiple printers, receiving bids for each new title on a competitive basis. Not only is this time consuming for the publisher, it extracts profitability from the printing industry. It has lead, in part, to the tremendous consolidation of book printers that we’ve seen since over the past two decades. I have in my archives a June 2007 article from the printing industry trade magazine, Graphic Arts Monthly (which was shuttered in 2010) stating that “of the 101 companies that appeared in Graphic Arts Monthly‘s first GAM 101 list of top printers, published in 1983, only 16 companies remain.” The most recent chart of the “Top 20 Book Manufacturers” was published in 2016, five years ago. The #1 player, Quad/Graphics, has exited book printing. Another is out of business. A couple have been acquired.

In theory consolidation removes capacity from book printing and so drives up the price printers can charge. Until recently there had been so much print capacity that pricing had a long fall. But with the bankruptcies of LSC and Edwards Brothers Malloy, Quad’s exit from book printing, and consolidation, capacity is now an issue and prices are higher. A question for publishers in seeking competitive pricing from the declining pool of print providers is whether the supposed savings offset the overhead of managing the competitive bidding process, and, more importantly, the cost of managing a larger supplier base.

(b) For most books, in the category below midlist, deciding the number of copies to print is straightforward. Add up the advance orders, add 50% and press “print.” If you’re short a few dozen copies, switch over to print on demand (POD).

Print on demand is now a viable alternative to offset printing for books that have little advance retail sell-in. Most of the orders received will be from libraries and colleges. The slightly higher cost per printed copy is more than balanced by the savings both from not maintaining copies in inventory and from eliminating returns (or nearly so).

(c) The number of copies to print both of midlist titles and of titles expected to hit the bestseller lists remains a crap shoot. In pre-Internet days book consumers were accustomed to sometimes finding bestsellers out of stock at their favorite bookstore. They were generally patient and relatively loyal — willing to wait a week or two until stock was replenished. In these days of information overload the intention to buy a single title is quickly lost or diminished if stock is not immediately available. The buyer moves on to the next written or visual distraction.

The Big 5, and other larger publishers, still have the power to stuff a lot of inventory into the supply chain. But the chain retains the right to return unsold books. This in turn created an industry of “remaindered” books, offered at heavily discounted retail prices.

Check out American Book Company, “the largest wholesale distributor of remainder, promotional and bargain-priced books.” This is where printing errors find a new home.

(d) The movement of books from the printer into the supply chain has become sophisticated, efficient and cost-effective. The largest publishers offer state-of-the-art warehouse facilities, as does Barnes & Noble in support of its 600+ trade stores. Smaller publishers can access similar distribution facilities from dedicated distributors.

A remaining issue is also a simple one: each digital copy sold can bypass the costs of physical distribution, regardless of its relative efficiency today.

Note: Mike Shatzkin writes with great insight on supply chain issues for trade publishers. See “The supply chain for book publishing is being changed by Coronavirus too” and more here: “www.idealog.com/blog/category/supply-chain/.